AGAINST THE SOCIAL STIGMA OF HIV/AIDS AND BIOPOWER. INTERVIEW WITH J. TRIANGULAR

J Triangular is an artist, activist, curator, neon poet, and videographer. Artivism united us, despite many times living in different territories. Common references, from films or underground figures, fill our encounters with passionate flashes. J inspires me to be brave and continue to seek a more just world through art, even though the questions that are asked or the positions that are taken may or will be uncomfortable. Here is our last dialogue, on the eve of the International Commemoration of the Fight against HIV/AIDS on December 1st.

aliwen: J, I found out about your work several years ago, circulating in the underground scene of Santiago, Chile. Together with your brother, Diego Barrera, you broke into the underground circuit with your gender irreverence, lo-fi style of video loaded with saturated colors and desiring bodies, and even organized the visit of Genesis Breyer P-Orridge to the country in 2014. What can you tell us about what the Celestial Festival meant for the Latin American scene?

J Triangular: Diego Barrera is a visionary artist, and also a spirit always ready to teach. Diego has created musical poems with artists such as XIU XIU, Phew, Lena Platonos, Laetita Sadlier from Stereolab, and he will soon release a new vision, so it is no coincidence that he was the one who will introduce me to Genesis Breyer P-Orridge for the first time. The Celestial Festival was not a concert, it was an expanded art experience. We intended to unite different art forms that will dialogue with critical thinking, to communicate a message through the rupture, investigating their languages that will help decentralize, achieve a break in the established ways to understand art and the world. This Festival sought to bring together different groups that would use art as a tool for emancipation against an oppressive society and against the industry’s appropriation of cultural artifacts, which ultimately prohibit our evolution.

Sharing with Genesis was very inspiring, from conversations about his friendship with Ian Curtis (the mythical Joy Division vocalist) to his love for our visual creations. He compared our work to Derek Jarman, his great friend, and to the tapes from Psychic TV that Scotland Yard burned. We saw all of our films together at the Blondie when there was no one but us. The musical documentary of the Celestial Festival will be exhibited at the MAMBO (Museum of Modern Art of Bogotá) during March and April 2022, as it is already part of the museum’s new collection, from the selection made by Eugenio Viola, Chief Curator of the MAMBO.

a: During 2019 you went to New York. You were chosen as the international curator in residence for the Visual AIDS, organization, which has dedicated itself since its foundation in 1988 (during the HIV/AIDS pandemic) to archiving, collecting, and making visible the work of HIV-positive artists and its surroundings. It was at that residence that you started the project The Whole World Is Watching a series of video essays on VHS that orbit around the question of the role of women in the fight against HIV/AIDS during the pandemic of the 80s and 90s, to the present day. How do you remember your time in New York? What did you discover about the role of women and femme subjects within the HIV-positive resistance?

J.T.: Every week, we record and edit a new episode for this TV show about community activism to motivate the fight against AIDS, renewing a sense of urgency to continue making the HIV/AIDS crisis a priority. With television, the internet, and newspapers as the main sources of information about HIV/AIDS, stigma develops from misinformation and misunderstanding of the disease. Referencing an ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) slogan: THE WHOLE WORLD IS WATCHING.

I always mention a situation that put me face to face with the stigma -when my best friend was in the hospital, my ex-partner kissed my forehead, and two nurses passed by and yelled at us that if it was not enough that my friend was dying of AIDS so that we would stop doing “those things”. That moment reminds me of the mythical Gran Fury project: Read my lips because kisses have never killed before or now. But thanks to those nurses I feel that they fed my need after my friend died (this year another friend in the middle of the Covid 19 pandemic also died of an AIDS-related disease) to generate artistic proposals that help fight stigma, because for stigma we still do not have medicine, and it is urgent!

During my curatorial residency, I discovered that lesbian women and trans activists, and the new wave of video activists, have been part of the fight against AIDS since its inception, but very rarely are they mentioned, and to this day I don’t remember any film that talks about these radical collectives when talking about women (trans and cis) in the fight against AIDS -they talk about them as passive participants, like sisters, mothers, like those who were always in the care of others, and even more dangerous as if women were immune to the virus. Do not forget that we call our community LGTBQ +, first the L thanks to the invaluable contribution of lesbians to the Gay community in the early days of the HIV/AIDS pandemic and until now.

Thanks to my residency I was able to delve into collaborative projects such as Fierce Pussy, Testing the limits, Diva TV, Wave Project, Paper Tiger TV, or Lesbian Avengers. My research was participatory so it allowed me to meet its members -I was able to meet Jean Carlomusto, the professor Alexandra Juhasz… I also had the opportunity to invite the Chilean writer Lina Meruane to be part of the series; her book Viral Voyages was fundamental for the whole process, especially the chapter called «The Syndrome of female disappearance.»

Every day was an adventure, my team was just An-An (my partner) and I, rushing to each interview, and filming in the most unexpected places. Visual Aids also gave me a lot of help and full access to the archive, so we were able to immerse ourselves in the archive of Keith Haring, Felix Gonzalez-Torres and read his postcards written in Spanish, the most intimate to his friends where he talked about parties, his fears, and his dreams; and Chloe Dzubilo’s archive with all her fanzines, punk songs, and trans-sensibility-awareness groups in hospitals… that experience is also very precious.

a: Some years ago you left the Western Hemisphere, migrating to Taipei where you have found new fields to explore, love, and resist. What led you to make this change? What things inspire you about Taiwanese culture and what challenges do you perceive living there?

J.T.: I was in New York doing an artist residency in a former postcard factory that became one of the most exciting artist residency programs since its opening in 1994, a creativity lab and incubator called Flux Factory, in Queens. One cold winter morning, a Taiwanese artist came to the studio next to mine, they were starting two residencies in New York at Flux Factory and Residency Unlimited at the same time: the sculptor Chen An-An. From the first time I saw them and help them to transport their toolbox to their studio, we fell in love and after four months when they had to return to Taiwan, they wonder if I would like to visit Taiwan to which I said yes immediately. Taiwan was not unknown to me, in fact, for any filmmaker, the new Taiwanese Film Wave doesn’t goes unnoticed -from the films of Tsai Ming Liang to Edward Yang or the wonderful filmmaker I recently discovered thanks to the WMWFF, film festival, Mi-Mei Lei.

My friend Tzuan Wu from the Other Cinema Collective officially invited me to exhibit in Taipei. That was my first time traveling to Taiwan, and it was a transformative experience. Everything inspires me about Taiwan, its 文化 – culture, its stories of resistance. Taiwan is the country that had the longest-lasting martial law in the world, the so-called White Terror era, and at that time the avant-garde and noise scene was vital. Its traditions, such as taking misbehaving children to hells made with life-size animatronics in Taoist Temples, or the peace you feel when drinking an Oolong tea from its mountains, the same peace that you feel being queer and being able to walk the streets safely. Taiwan is a queer refuge country for many non-normative identities throughout Asia, and the first in Asia in allowing equal marriage. With this I do not mean that equal marriage is what kuir activists have to prioritize, obviously there are still many factors that must be modified in this law to help people who are immigrants, or who wish to adopt, but Taiwan is on an excellent path. The only challenge may be the language but I am already in my sixth semester of Mandarin and singing Karaoke helps a lot in the process.

a.: Since you live in Asia you have been able to expand the momentum behind The Whole World Is Watching, with other related projects such as The Women’s Video Support Project and Hope Drops. Could you elaborate on these projects? With which women have you been able to collaborate in making visible the femme subjectivities gathered by these projects?

J.T.: It all started since professor Alexandra Juhasz, in episode 3 of the series, says to the camera: “And now the real activism begins, when reactivating the archive today we do something that can motivate change”. Her project WAVE (The Women’s AIDS Video Enterprise) was a seed of inspiration for our The Women’s Video Support Project. This is a pioneering project in Taiwan, never before have art and activism combined to give birth to a support group for women living with HIV who, using art and video tools, could exorcise their fears and pains with art, but also share their dreams and desires as a group. Thanks to our collaboration with Harmony Home and Lourdes Foundation, two organizations that protect the rights of people living with HIV in Taiwan, we were able to carry out this project. It has not been an easy start. When looking to finance the camera equipment, for example, a very famous organization in Hong Kong that I will not name denied us funds because they said that the project was not queer (even having a lesbian director and co-director). Many organizations feel that because it is a project carried out by women, it is not queer enough, it has to be carried out by the gay community to receive funding. But I believe that projects like this one help the gay community a lot because it is time that the stigma stop continuously criminalizing certain groups since we are all vulnerable to this virus.

From the beginning, the participants Annie Mami, Lu De, Victoria and I connected, despite me being seronegative. When I told them about the mission I have had since my friend died, we connected on a spiritual level because for all our faith is an element that has allowed us to continue. They were all very interested in learning how to use a camera to tell their stories; we also used cassette recorders to record snippets of the conversations we had after watching movie clips together or talking about what personal activism means, which gives it a character of dreamy and liberating confession to the narrative of the video. The result left everyone surprised and with a desire for more workshops like this one. For us it was very important to return the agency and ability to heal to the hands of women, who are constantly invisible. The Women’s Video Support Project is a workshop for women living with HIV in Taiwan; Hope Drops is the first video that comes out of this workshop. Our goal is to hold more workshops like this one during the next year and expand the opportunity for immigrant women can participate.

a.: Within your work as an artist, activist, and curator, you have developed the notion of counter-stories of the hegemonic representations of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, criticizing the hegemonic discourses promoted by agents of biopower, such as the medical institution and the media, which are used to violate the rights of those most affected by the HIV/AIDS pandemic. In a post-COVID-19 world, what is the relevance of working with this type of methodologies, given the new viral panics and old racist stereotypes that re-emerge in the form of Orientalism à la Wǔhàn?

J.T.: It is important to promote a more inclusive and truthful narrative, and for that art has incredible subversive power. My artistic practice, my aesthetic/political proposals are subscribed to the so-called artivism. We all know that in the seropositive narrative women were granted a supposed immunity, and this negligence caused that until today women are the ones who take the HIV test the least, and when they do it is already when they live with AIDS. In addition, when we watch movies, reports, even television series, people living with HIV tend to be shown as a passive victim, their agency is torn from them, and an imaginary of criminalization is built. This generates homophobia, AIDSphobia … it is an extreme manifestation of stigma. At the press conference of our project, Taiwanese activist Nicole Yang spoke of the need to show women living with HIV enjoying their lives; in joy there is also resistance, that is why you can see them all in our video -Annie Mami, Lude and Victoria- singing together in Karaoke. That creative liberation, from all those stereotypes that circulate for the AIDSphobia. Our methodology is transfeminist and has been constant since our first projects.

Regarding your second question, I think of one of my favorite writers, Arundhati Roy, who reminds us that the current stigmatization of Asian population is similar to what happened during Fascism, when the Nazis justified the genocide by saying that the Jews spread Typhus to the rest of the population. Unfortunately, I believe that this hatred that circulates was also fed by the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) because by hiding the information they already had since the end of 2019 about this dangerous virus, and by persecuting the doctors who wanted to raise the alarm, they caused many people to direct their hatred to the Asian population. I feel that what we are experiencing has also allowed us to empathize with nations that live under constant persecution from China, that which we call here in Asia the Great Bully, its countless human rights abuses ranging from organ trafficking and extermination of the meditation group of Falun Gong, Christians and all dissident spirituality and forced labor camps for the Muslim Uighur community. This pandemic has allowed everyone to open their eyes to the need we have to build support networks, mutual aid and put ourselves in the place of the other because until the last person in the most remote place in the world is vaccinated, this pandemic will not stop. This is why it is necessary to call up for equity in the distribution of vaccines, and to end the spread of conspiracy theories and fake news.

a.: This year, both of us will participate as activators -and, in your case, also as a commissioned artist- of Day With(out) Art 2021, the event organized by Visual AIDS for the international day that commemorates the fight against HIV/AIDS. This initiative emerged in the midst of the 80’s and 90’s pandemic, when Visual Aids, cultural agents -such as MoMA curators and Nan Goldin, among others- covered the works of art in museums to instigate to generate talks, protests or other instances for the dissemination of reliable information on HIV/AIDS. Could you tell us about some of the events that you will be participating in during this commemorative day? What is the importance of activating this type of instance in East Asia?

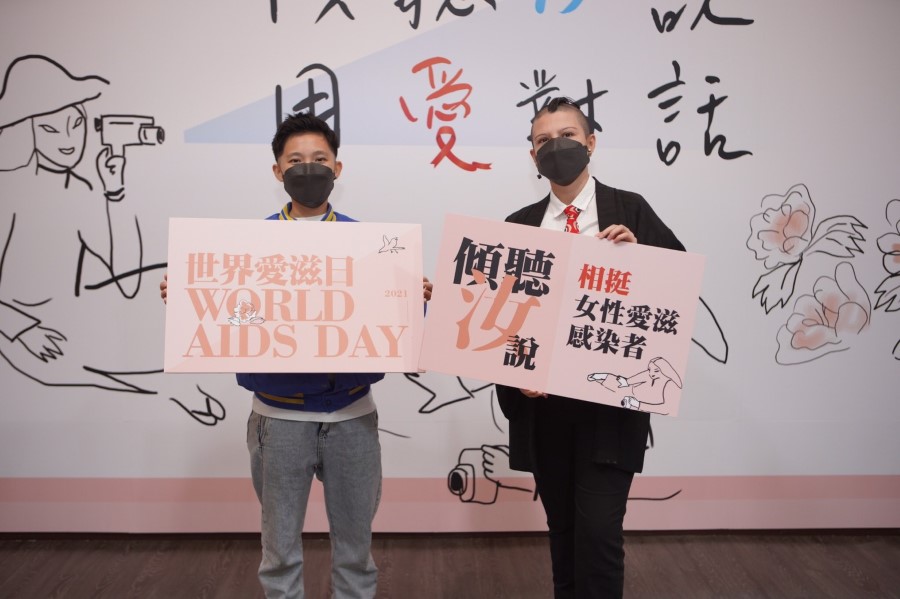

JT: This is the first time that a project carried out in Asia participates in this mythical and prestigious program. For me, it has monumental importance -as a Latinx artist based in Taiwan, I feel very proud of what we have created. For me, it was vitally important to take the program to places that had never been shown before, so I contacted spaces in Hong Kong,also an underground queer collective from Shanghai, Cinemq, and of course in Taiwan we have the unconditional support of Museums, Galleries, and activist organizations that fight against AIDS. Among the events that are important to mention there is the one with Taiwan AIDS Society 台灣 愛滋病 學會 on December 5, with a discussion about the project, and in the C-LAB, that will be showing the complete program in a loop. In Tokyo, you, your collective, and our friend curator Sho Akita, we’ll all be there for the Tokyo Aids Week. As a Latinx, I also focus on being able to expand it in Latin America. In Colombia, I am very happy that IDARTES will screen the program in loop at the Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Theater –it’s a special open-air screening-, and also at the District Cinematheque, thanks to Museo Q. In Chile, we’ll be presenting the project online together with Artishock, and in Valparaíso, the activist Susana Unzaga has been fundamental -together with the photographer Alvaro Yáñez- in not only finding four spaces to exhibit it, but also of carrying out actions in the streets and an open call for micro-stories. They’ll be presenting the Day With(out) Art for the first time in the city of Valparaíso. I have a special interest in the presentation that I will have together with MOCA LA, which will be broadcasted from the Museum this December 4. There is no excuse to miss Day With (Out) Art because it will literally happen in your city!

a.: I want to close this conversation by asking you about the importance of caring collectives as alternative ways to the neoliberal management of the body today. How can we tell stories of collective care, mutual aid, and solidarity? How can we reformulate community work as a form of healing?

J.T.: Care cannot be a service -it is a human right. It is our duty as artivists to subvert the hegemonic forms of representation of AIDS and to fight against the brutality of homophobia and AIDSphobia. We have to empower the chronically marginalized.

This year the theme of Day With(Out) Art is Enduring Care, and this has two meanings -the first refers to holistic thinking and a decentralized practice of reciprocal care, not only in terms of the patient-doctor relationship, but also regarding the importance of the community to encompass all parts of what it is to be a person. People living with HIV today do not want another long years of dependence on pharmaceuticals, they want the cure now. The care groups are also called affinity groups, because medicines do not protect from the stigma, stress, and loneliness that many people living with HIV face.

También te puede interesar

¡EL SIDA ES UNA EPIDEMIA SOCIAL! ENTREVISTA A LILI NASCIMIENTO Y HIURA FERNANDES

En esta entrevista conoceremos la historia detrás del corto “Aquela criança com AID$” (Ese niñe con $IDA) y de sus creadoras, Hiura Fernandes y Lili Nascimento (Brasil), el cual forma parte de un ciclo...

LO CRÍTICO-PULSIONAL DE LA CRÍTICA DEL ARTE EN ‘CRÍTICA DE BARRICADA I’, DE ALIWEN

La apuesta de "Crítica de barricada" podría ser definida como un posthumanismo transfeminista campuria que opta por des-esencializar la verdad del género inscrita en l*s cuerp*s generizados, abriendo la crítica del arte a los...

DAY WITH(OUT) ART 2022. HISTORIAS POCO CONTADAS SOBRE EL VIH Y EL SIDA

Por segundo año consecutivo, Artishock se alía con Visual AIDS en el Day With(out) Art 2022 al presentar Siendo y Perteneciendo, un programa de siete videos cortos que destacan las historias poco contadas sobre...