“THE EPILOGUE IS THE BEAUTIFUL MOMENT.” MARIA BERRÍOS ON THE BERLIN BIENNALE 2020 CURATORSHIP

“Rumor is the 11th Berlin Biennale has already begun” is the slogan stated on this Biennale website, which has been exploring spaces and places of the fragmented German capital since 1998, addressing critical issues of the current state of art. Biennials are processes. By means of them, relationships are established, sometimes sustainable, we are told on this occasion. The curatorial team consisting of Lisette Lagnado, Renata Cervetto, María Berríos, and Agustín Pérez Rubio, who define themselves as “South American curators” and multigenerational, is inspired by a common idea: collaboration through which each individual voice can be expressed.

“We are here to listen and learn. We bring with us baggage from the South, identities and artistic stories, devices to navigate the metropolis and share with its inhabitants. At ground level, we gazed though the curtains in an alleyway in the Wedding neighborhood. Here we have possible meetings, dialogues, and exchanging. We trust in unforeseen outcomes that are produced in the interaction with each other. We are not interested in making the process a spectacle, but in the common effort of being present, open, and in proximity. Since we are aware that our time is limited, we believe in developing sustainable relationships. Rumor is we have already begun,” comment the curators.

María Berríos welcomed us during one of the cycles of this biennial that began in mid-2019 with a series of three experiences and an epilogue. (Perhaps the end of an experience, perhaps the largest exhibition in the long 11th Berlin Biennale.) The first experience, exp. 1: The Bones of the World (taken from the title of a travelogue by Brazilian artist Flávio de Carvalho), took place between September 7 and November 9, 2019, at the ExRotaprint complex, in the Wedding neighborhood; The second experience, exp. 2: Virginia de Medeiros –Feminist Health Care Research Group, continues at the same location until February 8. After the closing of the third stage (from February 22 to May 2), the experiences comprising Berlin Biennale will be on display in various venues of the city, from June 13 to September 13, 2020.

Lisette Lagnado (Kinshasa, Congo, 1961, who lives and works in Brazil), being the curator of the São Paulo Biennial in 2006 and the director of the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage, would initially meet curator Agustín Pérez Rubio, born in 1972 in Valencia, Spain, and who directed the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano in Buenos Aires (MALBA). Later on, they would form a team with Renatta Cervetto (Buenos Aires, 1985). Pérez Rubio had worked before with Cervetto coordinating the education program in MALBA. In turn, Lagnado would invite María Berríos, a sociologist born in 1978 in Santiago, Chile, who has experience as editor of documenta 12 (2007) and lives in Copenhague. They have worked together in Madrid as curators.

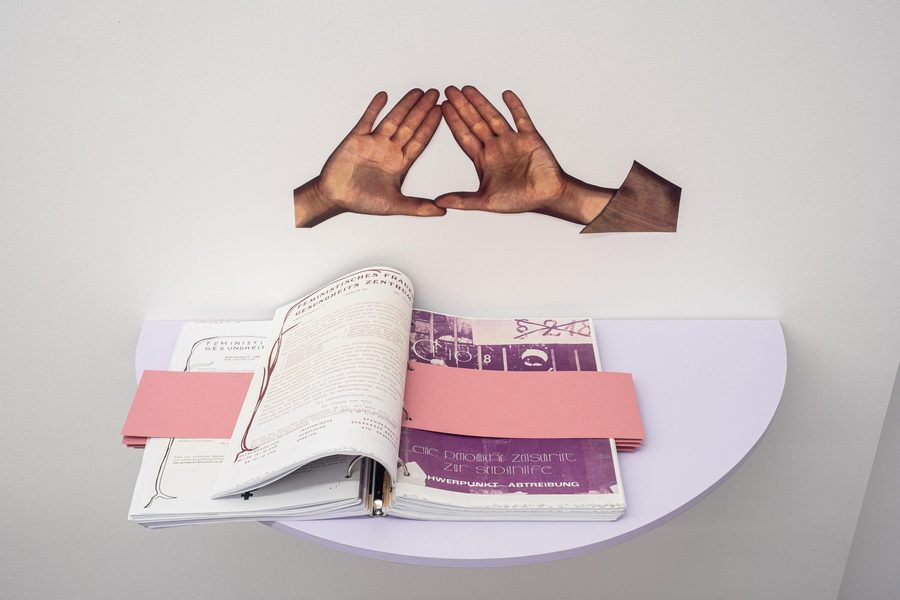

Teobaldo Lagos Preller: The biennial establishes different levels of commitment to daily life in the city. In this second experience, which correspond to three and an epilogue that would form the biennial as a one-year work-in-progress, there are elements that allow to reconstruct the history of a feminist health center in Berlin during the 1970s and 1980s. In this part of the space, we can see publications emerging from that organization. In a variety of ways, we could see an approach that goes beyond “just” the curatorship…

María Berríos: It depends a little on how one understands the curatorship and the biennial too. This “bomb” of names from biennials, exhibitions, that “big deal”…In that sense, we have proposed in several interviews that for us, as a curatorial team, it was important to consider that Berlin as a city has been devastated by that. Not only because of the Biennial itself, but also because of all this culture that comes, settles, and goes; from international art, pop-up projects, etc. Even people who pass by here. And it is worth asking oneself how that works and how it relates to different gentrification processes. This can be seen even if we thought about the biennial itself: ten years ago, the biennial could use an empty building and see how this has changed. I believe, then, from our point of view, that the way of interacting with the city has to be respectful and it has to consider how to deal with that violence of throwing this “bomb” of names and contexts to then just go away, which is what normally happens in biennials. There is some humility required to create an interrelation and also, I think that it has to do with our ways of working, which come from many different practices.

Our way of working is a slow approach. How can we reach that within the framework in which we find ourselves, which is quite the opposite? A biennial occurs every two years, but it is a very limited time. Doing biennials is crazy: running, installing, and leaving. Truth is that working process is always a continuous working process. All biennials that are taking place and that are going to happen in two more years, they are happening now. The thought of beginning with a first experience, a second experience, a third experience, and an epilogue consists of finding a way to be able to inhabit that period of time, build trust, and create relationships. What we have sometimes called “sustainable relationships” not only have to do with the city, but also with the artists. And what we want is reaching that space within the framework of what a biennial or a global exhibition is, which in general it is not thought for that, at all. I am not saying it looks like a problem, it is something that our team does in good faith, but open this process in that manner causes difficulties to the existing institutional structures, to the way of working of the biennial itself, because working in a process actually becomes defending that process that one way or another is always going to take place. It is a matter of trying to make that process of approaching, of research, more permeable through a curatorial methodology that basically consisted in a production of experiences. The first of these, titled The Bones of the World, was almost literally taking things out of our suitcases. It was a very personal exhibition, in the feminist sense of the term, not an autobiographic or a narcissist conception of the personal, but in terms of the stories that hold us, that we share, stories that we carry with us, but at the same time these are the stories that intercede in our relationships with others. There are also stories from Berlin that we were just getting to know. In the curatorial text we wrote, we referred to those “moving stories”. There are moving stories in this moment as well, when the world is so broken, so to speak, or at least in the process of breaking down. It can be said that there is something in the making, but at the same time there are also very dark forces that have been revealed in an exacerbated way since we started this biennial. I think the day we made the public announcement was the day that Bolsonaro won the presidential election in brazil, which makes you feel like you are almost in the 1930s with these sexist men in power… I mean, we can lose everything we have accomplished so far. It is what happens now in Chile, it is something no one would have imagined: the state terrorism that was practiced throughout democracy against certain oppressed segments of the population could become widespread and the rest of society did not seem to care enough as to give political relevance to the unacceptability of such treatment. I am talking specifically about the Mapuche people, indigenous population, and others marginalized sectors. The State continued with the dictatorship violence against those people all this time, which is terrible, but no one imagined that instead of taking the responsibility for those systematic violations, that unleashed violence would spread to the majority of the population; no one imagined that militaries would be on the streets again… Declaring the curfew again is from a brutal violence to the historical memory.

TLP: To the extent that the parameters of democracy are in crisis at the moment, the editorial and curatorial criteria are also in crisis. How do you think this curatorial methodology based on collective work responds to that generalized tension?

MB: Yes. I think that, in that context, if you do something completely isolated… I do not believe in that, in that way of seeing and making art. For me, art is always about the world. It comes from the world. It is not something that enlightens me, nor does it mean that “we are going to revolutionize”, at no time do we think that way. However, I think that when these kinds of things are happening, it is absurd and violent to turn your back on them and believe in this alleged autonomy of art. It is not possible to think that one can be and live in abstract in the world from which things come. No one has invented that system yet (laughs). In that sense, the biennial has to talk about what is happening, it has to relate in some way to the people, the experiences, it has to make room for that political corporeality that is ours too. Curatorially, the permeability is highly relevant as well as how things are re-signified in that context: not everything is about the same intention that it had at the moment it was made, but also about what happens when it is related with other works, in an institution, in a context.

TLP: How collective work is useful to respond to that necessity?

MB: On the one hand, there are fewer blind spots, of course. Besides, it goes to a conceptual level: this issue of curatorship, of the curator as another artist or of the great artist, who seems to me to be a retrograde figure, is outdated… Honestly, all biennials are done in teams. But just one person signs it and that is already problematic. It is just easier, because there is only one person who is in charge and decides. Doing it in groups of four is making things difficult for us (laughs), but it is nicer too. We are notoriously different: Agustín (Pérez Rubio), for instance, was Director of museums. He has a more institutional profile. As for me, I have worked in institutions, but my practice is also very collaborative and self-managed. I have always worked in a self-organized way, doing my own publishing house, setting up projects at home, which have been very valuable experiences to me, even though I have worked in institutions too. I learn from both sides, but perhaps I would become tired in just one. On the other side, I have in common with Lisette (Lagnado) a very deep and long research work. In almost every exhibition I have made, which arises from a research process, a network of relationships is formed that lasts a lifetime. It is not like “this is my topic this year and next year I will make x…”. They are long term relationships, extended families in a sense: they come and go, and come back and go. That is how Lisette and I met, working together on it. She is a philosopher, a journalist, and she have done biennials before, such as the São Paulo. We have done publications together. Renata (Cervetto) has a profile more related to the education, she works with the community, and she studied curating. None of us have curating studies. I am a former sociologist. Anyway, we have quite different profiles. The intergenerational aspect is very important. Even if the gap is not that big, there are generational marks that are beautiful, we try to deal with them together. Create a collaborative curatorship is just more transparent: instead of only standing out the biggest or most famous name, we accept collective work, though it is difficult. It is not big news either, now several institutions are working with curatorial collectives.

TLP: Right, it always draws attention the issue about how and within what parameters a biennial is created. On the other hand, Berlin is not a biennial like São Paulo or another one that has a global trajectory or the same relevance. Despite being at the center of a European power, it is a biennial that is somewhat peripheral. It addresses issues that are not exclusively related to the major world centers. I find that interesting. On the other side, there is a vocation to concentrate on the local, which I think is something characteristic. At Bergen Assembly we talked about a Core Group, a curatorial and artistic team that deployed positions in form of curatorships or artworks in a more or less free way. If you had to put a name to the Berlin Biennale team, what would it be?

MB: I do not know if a get this right, are you asking me to give you a curatorial category?

TLP: What are the ideas that would allow to give a name to this biennial?

MB: I consider that all the aspects of the work are curatorship. In order to be able to work, there are certain responsibilities, but they are not so “clean.” Insisting on those dirtier categories is not so common, or perhaps it is not that it is not so common, but trying to share those roles is not easy. It is obvious why it is not so common: you cannot be in everything, nor can everyone be in everything. However, it was important for us, for instance, to participate in the decision of which artists we are going to call, which publications, and which criteria in general we are going to take. That is why we decide to work nine months before the “usual” opening, which is for us a way of respecting that action process. There are very different ways of facing the role of the curator and I would say that exists even within our team. Nevertheless, I think that non-segregation is something that characterizes a common view. In the first experience, in the first room, we can see the Die Remise project. It is about the living archive and experimental exhibition space of an elementary school located in Kreuzberg, in charge of Carmen Mörsch in cooperation with Markus Schega, the director of the school, invited artists, and the school’s students. What they did was inviting artists to work with the archive and the students. For us, this is relevant as an artistic proposal and not just as an artistic mediation. I think that in contemporary art there is often a terrible segregation of education, as if it were a service for “the real art”, as if the educational or mediation work were the reproductive work of art. And that is deeply shocking, if you think about it in relation to, for instance, how popular the subject of infancy or childhood has become.

It is fascinating to see how for a long time, in the 60s and 70s, it was thought in a much more experimental way about childhood, there was an interest in addressing the forms of experimentation present in childhood. The majority of the exhibitions that we see close to the experimental childhood or the playgrounds are made for adults, or even more specific for architects. They are not for children and many times there is not even an effort to include them. There is a project of Palle Nielsen titled The Model, which is like a climax of that moment. He made a gigantic adventure playground inside a museum. The adults were watching, there was a slightly troubled voyeurism, but at least they were present. Now it has reached a level in which that voyeurism observes black and white pictures of children. At most it is considered to have a day-care center in an artistic institution. I, as a mother, really appreciate it, but when there is a day-care center or childcare, it is about a service: children are placed in a room so they can play, do a project, and not bother the adults while they are engaging with “serious” art. This phenomenon can also be seen in the practice of many artists whose work includes collaboration with children. It is the institutionality of art along with its mechanisms and practices that end up segregating the practice of certain artists who work in the art mediation, when they work with children or young people. These kinds of segregation, as it happens with the Outsider Art, for instance, whose legitimacy within the art world is based on being outside…

TLP: Prioritizing in your production conditions…

MB: Of course. In our first experience, there were many things in the exhibition that literally came from our houses, and they were produced outside the art system, which could be considered as handicraft. There were also works of people with various mental health diagnoses. There was an embroidery that accounted for a type of work arising from women’s centers that started as health and childcare associations during the 50s and 60s in Egypt, and then they gave rise to a type of handicraft that nowadays is treated as if it were something quite traditional. It was something that women and children could do. The embroidery stitch is the most basic of all, it was an activity that got women out of their houses and allowed them to gather among themselves… All the material that came out of that place now looks as if it were traditional culture, almost millenary. That piece that was quite simple, a scene of animals to the north of the Nile River, explained that beautiful story. Each one of the pieces we showed had a story. What we did was exposing ourselves a little bit. Understanding the exhibition space as a space of mutual exhibition. And the collective work is also a mutual exhibition space in which the result is, by the way, unpredictable.

TLP: As a contact area…

MB: Yes and, in that sense, it is also a public space. Which it is not, but it should be thought as such. What is the use of all of this if there is not contact with each other?

TLP: What can we know about the Biennial exhibition?

MB: This is already part of the exhibition. This space, what we do in ExRotaprint is as relevant as what is going to happen this year. The idea is having a conversation and raising some concepts… What is coming is a continuity. However, the idea is not reaching a culmination or a climax, but we could even be talking about an anti-climax, since by then everything will begin to end. We would find ourselves then in front of the corpse of the process, I mean, a body that passes to another state, a death in a sense. Nevertheless, that death is not a fixed state, but a passage in which each one of these pieces, practices, projects, and persons return to their own social fabric, leaving behind our care -which will no longer be needed. The epilogue is the beautiful moment in which the works begin to return to the world to continue with their lives.

Translated by Constanza Figueroa

También te puede interesar

Fuso | Anual de Video Arte Internacional de Lisboa

Entre el 22 y 27 de agosto se celebró la 9ª edición de FUSO | Anual de Video Arte Internacional de Lisboa, con una programación exclusiva seleccionada por los curadores Solange Farkas, Jean-François Chougnet,...

ALTERAR SIN MOLESTAR. SOBRE LA CURADURÍA DEL PABELLÓN CHILENO EN LA BIENAL DE VENECIA

Si Venecia es el evento más importante del mundo del arte, al ver "Miradas Alteradas" uno llega a preguntarse por la pertinencia de esta propuesta como representante del pabellón de un país como Chile...

Voluspa Jarpa Trae a Chile Parte de su Exitosa Muestra en el Malba

Tras el rotundo éxito de su exhibición Nuestra pequeña región de por acá, que acaba de cerrar en el MALBA de Buenos Aires -donde compartió presencia con Yoko Ono-, la artista chilena Voluspa Jarpa...