FIRST US RETROSPECTIVE IN 40 YEARS DEDICATED TO SOPHIE TAEUBER-ARP

The Museum of Modern Art presents Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction, the first major US exhibition in 40 years to survey thismultifaceted abstract artist’s innovative and wide-ranging body of work. The exhibition explores the artist’s interdisciplinary approach to abstraction through some 300 works assembled from over 50 public and private collections in Europe and the US, including textiles, beadwork, polychrome marionettes, architectural and interior designs, stained glass windows, works on paper, paintings, and relief sculptures.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp is organized chronologically, beginning with works produced soon after the artist’s move to Zurich in 1914, and ending with those created during World War II, in the months immediately preceding her untimely death in 1943. Related works across disciplines are placed in proximity to one another to explore the artist’s distinctive cross-pollinating approach to composition, form, and color.

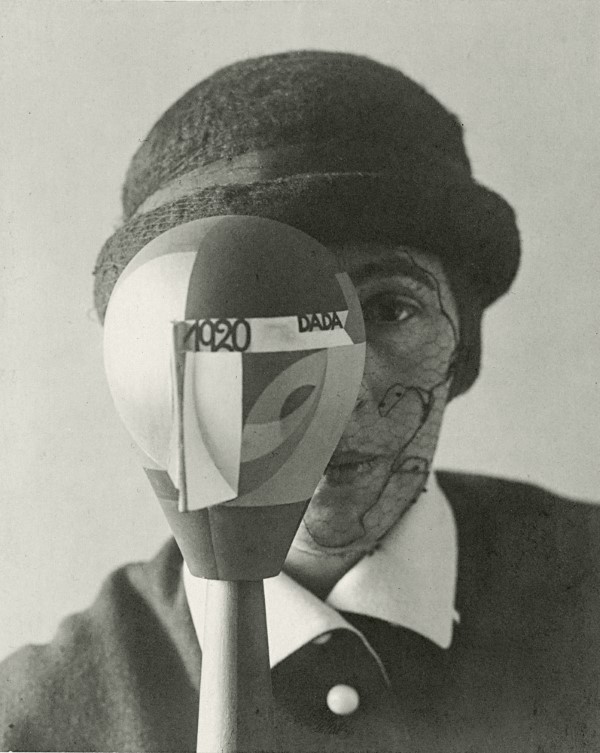

Among the significant bodies of work included in the exhibition are Taeuber-Arp’s vividly colored, abstract textile studies; her decorative art objects, such as beaded bags and necklaces, rugs, embroidered tablecloths and pillow cases, and turned-wood containers; the polychrome marionettes she designed in 1918 for the puppet play King Stag; and a remarkable group of small, stylized sculptural heads associated with Dada.

The exhibition also presents works related to the various interior design projects that Taeuber-Arp carried out in the late 1920s in Strasbourg, most notably the decorative program for the Aubette entertainment complex; furniture and working drawings for the interior design and furnishing commissions she received after moving to Paris in 1929; abstract paintings and painted wood reliefs that employ a reduced geometric vocabulary, done in the 1930s, when Taeuber-Arp participated in avant-garde artists’ groups such as Cercle et Carré (Circle and square) and Abstraction-Création; and precisely controlled yet seemingly free line drawings made during World War II, while Taeuber-Arp was living in exile in the South of France.

BEGINNINGS: THE TEXTILE GRID

After completing her studies in Munich and Hamburg, Taeuber-Arp returned to her native Switzerland in 1914, at the beginning of World War I. She settled in Zurich, where she established herself as an independent craftswoman, specializing in textiles, wooden objects, and beadwork, which she designed using boldly colored abstract arrangements and stylized figurative forms.

During these years, Taeuber-Arp developed a distinctive formal vocabulary based on the grid structure of the open-weave canvas employed in embroidery, a pattern she transferred to other supports and used as a point of departure for abstract and dynamic compositions. In 1919 she began to produce independent studies, experimenting with loosening the grids into more open-ended patterns.

DESIGNS FOR MODERN LIVING

Thanks to the Aubette project, Taeuber-Arp and her husband, Jean (Hans) Arp (1886-1966) were able to afford to buy a plot of land in Clamart, southwest of Paris. There she designed a studio-house—a shared working and living space—where the couple settled in 1929. Built from limestone and designed with simple geometric outlines, the studio-house followed the functionalist principles espoused by the Bauhaus school, in Germany, and other proponents of modern architecture in Europe. Taeuber-Arp also designed modular, recombinable wooden storage units for their home, in keeping with the idea that modern life entailed rethinking everyday living.

Following her move to France, Taeuber-Arp positioned herself as a designer of interiors and furniture. From 1929 to 1935 she received several commissions in Paris, Basel, and Berlin, which allowed her to explore modern materials while continuing to apply rational and practical concepts to her designs. Although Taeuber-Arp would have happily pursued additional projects, by the late 1930s, commissions were increasingly rare.

BODIES IN MOTION

Taeuber-Arp began studying expressive dance in Zurich in 1915, the same year she met her future husband, who introduced her to members of the antibourgeois Dada movement. She participated in their irreverent activities, such as Galerie Dada’s opening, at which she performed an abstract dance.

Her experience as a dancer may have informed her 1918 designs for the puppets and stage sets of King Stag, an eighteenth-century play adapted into a parody of psychoanalysis, featuring characters named Freudanalyticus and Dr. Oedipus Complex. The deliberately antinaturalistic puppets, made of elementary geometric shapes that reveal the bolts connecting their limbs, received great praise from the Dadaists.

Soon after the play’s first performances, Taeuber-Arp exhibited three works as “studies for marionettes.” It is likely that these were the celebrated turned-wood sculptures that are now often referred to as “Dada heads,” which would intimately link those iconic and indeterminate objects to her King Stag success.

PEDAGOGY AND PROCESS

During her tenure at Zurich’s Trade School, where she taught design and embroidery between 1916 and 1929, Taeuber-Arp wrote two essays that illuminate her thinking about the role of artists and designers in society. “In our complicated times,” she asked, “why conceive ornaments and color combinations when there are so many more practical and especially more necessary things to do?” The answer, she asserted, had to do with a “deep and primeval urge to make the things we own more beautiful.”

Taeuber-Arp developed specific working methods to make her creations from that time “more beautiful.” In 1922 she wrote to her sister that she had produced “a whole series of small watercolors,” which she could “easily rework at any time into beaded bags, cushions, carpets, and wall coverings.” A number of such designs demonstrate the collagelike compositional process that facilitated the migration of her motifs from one work to another.

TRAVEL PHOTOGRAPHS AND CITYSCAPES

Starting in the 1920s, Taeuber-Arp and her husband made frequent vacation trips, often connecting with artist friends as they went. In the summer of 1923 they spent time with Kurt Schwitters and Hannah Höch on the island of Rügen in Germany. Two years later, they stayed with Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings on the Amalfi Coast, in Italy. And in 1929 they traveled through Brittany with Robert and Sonia Delaunay.

Taeuber-Arp’s interest in the structure of monuments and the built environment is evident in her photographs from these travels. Through the camera’s flattening lens, she captured abstraction in the interplay of shapes in stone walls, arches, and triangular rooftops. In her works on paper, also made during these trips, she translated architecture into colorful compositions, simplifying and omitting details in order to render the cityscape as a relationship of geometrical elements.

STRASBOURG INTERIORS

In 1926 Taeuber-Arp began to spend time in Strasbourg, where her husband had moved in order to obtain French citizenship. There she received a series of interior-design commissions, sometimes carried out with Arp, including a hotel, several private homes, and, most significant, the Aubette entertainment complex, a project on which the Arps invited the Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg to collaborate.

For the Aubette, Taeuber-Arp designed several rooms in which she covered the walls, ceilings, and, sometimes, floors with square and rectangular fields of color, enlarging her characteristic grid into immersive abstract environments. This shift to architectural scale marked a major turning point in her career. Art historians later called the Aubette the “Sistine Chapel of abstract art,” but the decorations proved too daring for the tastes of the time. In the 1930s major alterations destroyed this total work of art.

EARLY PARIS ABSTRACTIONS

Taeuber-Arp’s move to France marked another major shift in her career. Freed from her teaching obligations, she devoted more time to her fine-arts practice and became involved with the Parisian avant-garde. In 1929 she joined the abstract artist group Cercle et Carré (Circle and square) and, later, its successor, Abstraction-Création, in 1931. During these years, Taeuber-Arp exhibited her first easel paintings and developed a distinctively dynamic form of geometric abstraction, with subtle irregularities that convey both balance and movement.

Taeuber-Arp turned to nonobjective painting at a moment when various ideologies of abstraction were converging in Paris, where many exiled artists were congregating as their home countries’ increasingly repressive regimes grew more hostile to nonfigurative art. Abstraction-Création explicitly equated abstraction with freedom: “Any attempt to limit artistic efforts according to considerations of race, ideology, or nationality is intolerable,” the group’s journal announced in 1933; “we commit . . . to total opposition to all oppression, of whatever kind.”

ABSTRACTION IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS

Taeuber-Arp had explored the interplay of two and three dimensions in earlier projects, and in the mid-1930s she extended these investigations into colorful wood reliefs. These sculptures carry the visual rhythms of her paintings into real space, inviting us to look at them from multiple angles. She also began to incorporate sinuous curves next to straight lines to produce compositions suspended between the organic and the geometric. One recurring motif is a shape resembling a truncated amphora, which Taeuber-Arp frequently combined, separated, adjusted, and repositioned.

Many of Taeuber-Arp’s works from this time were included in major abstract, Constructivist, and Surrealist exhibitions across Europe in the mid to late 1930s. In 1937 she was one of only two women to participate in the Konstruktivisten (Constructivists) exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, which, she said, attracted everyone “who [had] a triangle at the end of their brush.” With twenty-four of her works on view, it was the largest presentation of the artist’s oeuvre during her lifetime.

THE WAR YEARS, DRAWING WITHOUT END

As tensions mounted in Europe in the late 1930s, Taeuber-Arp continued to develop her practice, creating wood reliefs, gouaches, paintings, and collages. “I think we all have to continue working, despite it being very difficult to find the necessary focus,” she wrote in 1939. That same year, she published what would be the last issue of Plastique/Plastic, a magazine intended as a channel of communication between the European and American avant-gardes.

Taeuber-Arp and Arp fled to the South of France a week before German troops marched into Paris in June 1940, and eventually found refuge in a town called Grasse. Because supplies were scarce, Taeuber-Arp went back to working primarily on paper, producing lyrical colored-pencil drawings. In late 1942, to escape the German and Italian occupation of the free zone, the Arps moved to Zurich, where, in January 1943, Taeuber-Arp died of carbon-monoxide poisoning in her sleep, a few days shy of her fifty-fourth birthday.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction is organized by The Museum of Modern Art, Kunstmuseum Basel, and Tate Modern, by Anne Umland, the Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture, MoMA; Walburga Krupp, independent curator; Eva Reifert, Curator of Nineteenth-Century and Modern Art, Kunstmuseum Basel; and Natalia Sidlina, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, London; with Laura Braverman, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture, MoMA. Prior to its presentation at MoMA, the exhibition was shown at the Kunstmuseum Basel (March 19–June 20, 2021) in Taeuber-Arp’s native Switzerland, and at Tate Modern in London (July 13–October 17, 2021), where it was the first-ever retrospective of the artist in the United Kingdom.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction

November 21, 2021–March 12, 2022

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Floor Three, The Robert B. Menschel Galleries (3 East)

También te puede interesar

SEBA CALFUQUEO Y CAROLINA ILLANES EN «RIGHT TO INHABIT», LONDRES

En marzo de este año, los artistas chilenos Sebastián Calfuqueo y Carolina Illanes realizarán proyectos artísticos en Gasworks y la Tate Modern de Londres como parte del programa público de Latin Elephant 2021-2022. En...

REEDITAN “LA MANZANA DE ADÁN”, DE PAZ ERRÁZURIZ, CON FOTOS INÉDITAS

Fundación AMA reedita el libro La Manzana de Adán de Paz Errázuriz, considerado como un referente imprescindible para los estudios de fotografía en Chile. Las fotografías a travestis que la artista chilena tomó entre...

CONVOCATORIA: DESOBEDIENCIAS PRÁCTICAS DESDE LATINOAMÉRICA

Este encuentro de dos días tiene como objetivo reunir a artistas, investigadores, activistas y académicos para abrir una discusión sobre colonialismo, anticolonialismo, decolonialismo y descolonialismo, centrándose en las diferentes formas que toma el poder...