RODRIGO VALENZUELA: NEW WORKS FOR A POST-WORKER’S WORLD

By Paula Kupfer

At the height of early industrial steel production, workers were treated as engines of sorts, their bodies wrung out of vitality, transformed into glowing steel bars, sweat, and capital. As one steelworker told the writer Hamlin Gardland in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1894, “You start in to be a man, but you become more and more a machine.” Another worker said, of the physical labor, “It sweats the life out of a man.”

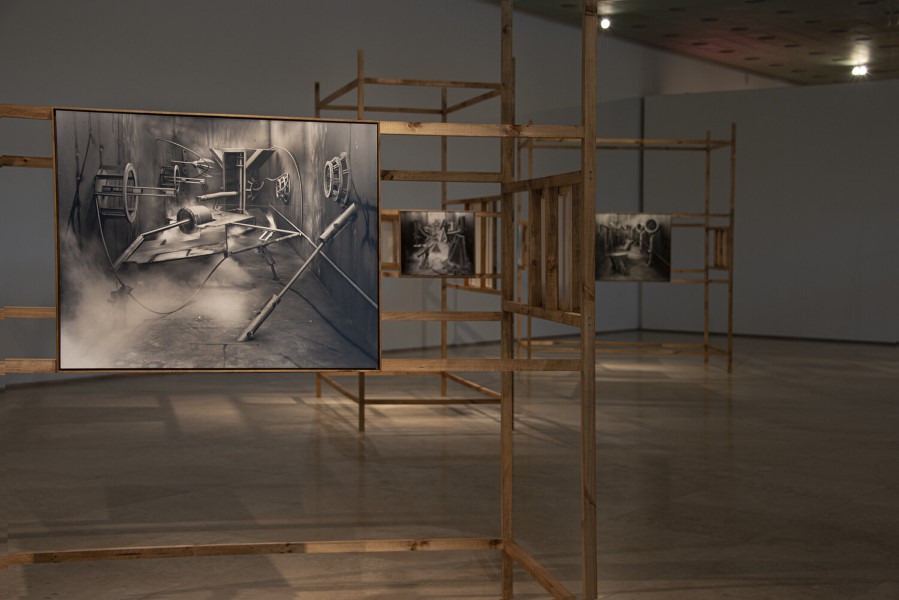

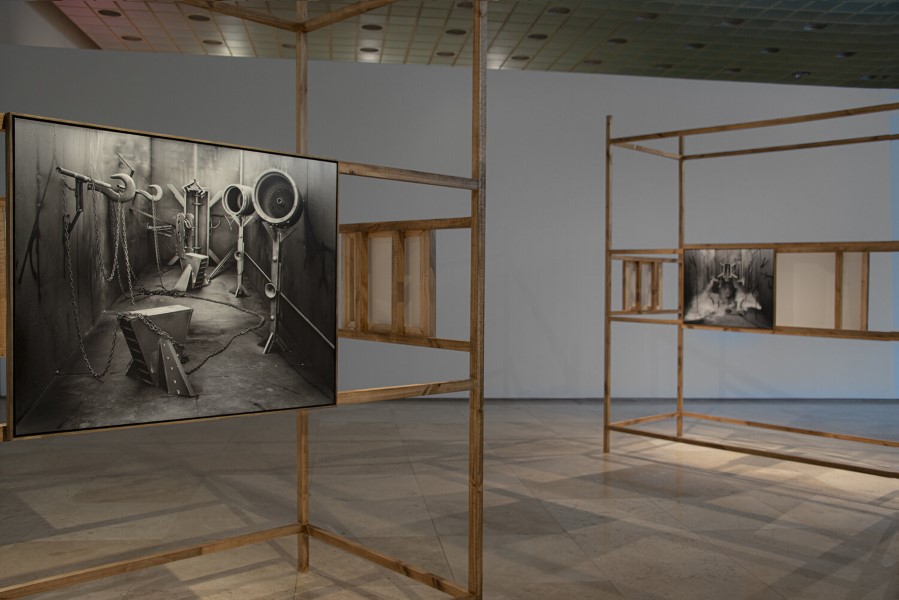

The smoke in Rodrigo Valenzuela’s new series of photographs invokes the blazing steam and flaring white heat of steel in the process of formation, but also the perspiration of labor indefinitely suspended in the air. The hazy constructions recall old photographs of iron and steel mill factory floors, but they do so without the workers who brought the huge engines to life and lent them their colossal scale.

In these depopulated photographs, viewers are left to their own imaginative devices, prompted to envision alternate possibilities to that of a future of obsolescence. The photographs’ silvery tones recall the sheen of W. Eugene Smith’s photographs of Pittsburgh in the 1950s, of that peaking decade preceding precipitous decline, and of the photographic assignment that nearly drove him to madness.

Valenzuela’s contemporary Frankensteinian contraptions are ominous, uncanny, and some have a sinister edge, embodied by the threat of metal chains and hefty hooks. Others are delicate, almost sympathetic. By allowing the recognition of some of their parts—such as the spidery legs of a repurposed umbrella—the artist offers a glimpse of his ingenious process of reuse. Photography, the medium so attached to reality, is here put the task of world-creation, generating visions of afterlives in which the ills of capitalism might be combatted with imagination.

These images are both in and out of time. They suggest the roaring steel mills of the past, quickly abandoned once outdated. They also offer a retrofuturistic vision, the look of alternative futures in which workers and machines came up with a better plan than their mutually assured futility. But as stand-ins for the growing numbers of workers dispossessed due to automation, the pictures also conjure a more disconsolate view of the future. In their invocation of histories of labor, and of industries created by humans in order to displace themselves in the service of capital, these photographs intersect with the struggles for unionization, a longtime interest for Valenzuela. They stress the body’s worth—both single and collective—as well as that of rest and pleasure.

The assemblages also implicate the fantastic, in the idea of overlaps between body and machine. Have the laboring bodies indeed become engines, alchemized through the repetitive, perilous work into rattling, thunderous machines? Or is it that the machines have turned fleshy and sensuous, and, desiring more than disuse and oblivion, come alive in a raucous carnival, pushing into each other, transpiring profusely—not from toil but release?

Valenzuela beckons the viewer to partake in the fiction, in the sooty possibilities of what might happen when the workers are gone: condensation filtered by pulsating lights, drudge melting into ecstasy and abandon. In their projection of a post-worker’s world, the series speaks to the elimination not only of individual laborers but of the idea itself of the work force, pushed aside by the very shapes we see here: odd machines and automation, engines that no longer require an operator, but that rage when no one is watching. The workers have left the factory. For tonight, or for good?

New works for a post-worker’s world, by Rodrigo Valenzuela, was on view from June 16 to July 22, 2021 at Patricia Ready Gallery, Espoz 3125, Vitacura, Santiago de Chile

También te puede interesar

VICENTE MATTE. TOMAR FORMA

Vicente Matte hace pinturas que son muy personales. La vida interior que él les entrega no es sólo el resultado de las historias que ellas mismas sugieren, sino también de la manera en que...

Una Escultura Sentimental:historia de un Joven

Galería Patricia Ready, en Santiago de Chile, presenta hasta el 20 de abril la muestra "Semiprecioso" del chileno Miguel Soto (Santiago, 1990), donde el artista analiza cómo la ficción se apodera de los relatos...

MARTÍN KAULEN Y SU ARTE CINÉTICO PSICOLÓGICO

En su primera exposición en Galería Patricia Ready, Martín Kaulen presenta un conjunto de 17 trabajos que, desde el uso de la madera como material de trabajo, propone relacionar la capacidad de abstracción del…