BEAUTIFUL DISTRESS: ART AND MENTAL HEALTH. MARTÍN LA ROCHE IN CONVERSATION WITH CAROL STAKENAS

[ESPAÑOL]

Carol Stakenas, curator at-large for the Social Practices Art Network (SPAN), talks to Chilean Amsterdam-based artist Martín La Roche (1988) about his three-month residency experience at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, as part of the Beautiful Distress Foundation (Amsterdam) program, whose mission is to raise awareness of mental distress under the belief that art is pre-eminently capable of articulating and representing the human condition.

Beautiful Distress uses art to tell stories of psychiatry to a wide audience that, by not coming into direct contact with mental illness, is submerged in ignorance and, therefore, stigmatization. Although mental illnesses evoke negative emotions in those who suffer them, they are also a rich source of creativity. By uniting these two worlds, that of art and psychiatry, Beautiful Distress seeks to validate the world and the experience of the mentally ill.

Carol Stakenas: Okay, let’s begin. First, thank you for inviting me to be in conversation, Martín. I really enjoyed getting to know you and your creative practice during your Beautiful Distress residency at Kings County Hospital in fall 2018. Now, we have an opportunity to reflect on your experience with perspective since you’ve returned to Amsterdam. To start, tell us about the Beautiful Distress residency. Why did you choose to participate?

Martin La Roche: Thanks, Carol. It has been very important to share with you as well. To remember what happened gives me a different understanding of my experience.

Beautiful Distress is a Dutch organization that hosts a residency in the Behavioral Health Service of the Kings County Hospital in East Flatbush Brooklyn, where artists work and live in the environment of a mental health institution for three months. In the Netherlands there is a project called Het Vijfde Seizoen (The Fifth Season) that has been doing something similar for 20 years. Beautiful Distress got inspiration from them. Still, they wanted to go beyond the Netherlands, and that’s why they got in contact with Carlos Rodriguez Perez at Kings County Hospital. They started an exchange and collaboration in 2014.

The residency was not conceived as an art therapy project (music therapy, drama therapy, art therapy, etc.), instead, Beautiful Distress invites artists to live in the hospital and give them time for their practice. They think that art can be a good translator for mental health issues. There is a huge stigma around mental health in society, and they believe that art is an excellent tool to break these negative patterns and produce communication instead.

Personally, I wasn’t looking for this residency. It came to me through a chance encounter. One day at an art opening, I ran into Wilco Tuinebreijer, a psychiatrist interested in art. Since I was starting to speak Dutch, I wanted to practice. So I shared that my father was also a psychiatrist and told him a story about my father’s office. I explained how one day, a patient asked him if it was possible to leave an object as a way of saying thanks for the therapy. My father agreed. So, the person left a small memento. At one point, another patient asked about that object – after learning about this gesture, asked if it was also possible to entrust an item. So, he or she also decided to hand over something too. Then a third patient came, and a fourth one, and a fifth one, and so on. Now the office hosts a super eclectic cabinet of curiosities that has been built through many years of therapy with each work representing just the tip of the iceberg of what happened for them in that intimate world.

When I told this story to Wilco, he asked me, “How does this cabinet relate to your art practice?” I was not prepared for that question. I never thought about it, even though there were obvious implications to my artwork and interests. Then Wilco told me he was the director of Beautiful Distress. We shared a commitment to exploring connections in the psychiatric world—between therapy, objects, their stories, and working with a group of people. After a few more encounters, I was invited to do the residency. So, in a way, this opportunity came to me. It was an invitation that I wasn’t looking for, but I felt that I couldn’t say no.

CS: I’m glad you didn’t! So, in September 2018, you arrived at Kings County Hospital, which is owned and operated by NYC Health + Hospitals, a municipal agency that runs New York City’s public hospitals. The hospital covers 40 acres in the neighborhood called East Flatbush, Brooklyn. It is what one would call an anchor institution in that community.

Please give us an idea about the plans you brought with you as a starting point. And when you got to the hospital, what did you find?

MLR: I had in mind to create an object-based project associated with the practice I experienced in my father’s office, using the idea of his cabinet was a starting point. But quickly, I realized that my relation to psychiatry was one filled with mystery and imagination. There is a taboo around making mental health issues public, so if you haven’t experienced it personally or through a friend or relative, you don’t know much. I grew up knowing about the existence of mental health issues through my family history, but then I realized that many times this knowledge was about not knowing. Here’s a concrete example: I would go to my father’s office after school so we could go home together after he finished his work. I saw all these objects in the bookshelves and the floor, and knew they were witnesses of something else, but I didn’t know exactly what or how.

So, I shaped my project around this absence. I wanted to recreate this practice that was so familiar and, at the same time, completely unknown to me. I thought this method would allow me to work with objects and their stories in a group context. I wanted to invite patients and staff in the hospital to work on something that I called the “therapy bookshelf.” I planned to invite them to bring objects to leave on a shelf and tell stories to the group, followed by a weekly reconsideration of these stories. I had the idea to establish a particular space in the hospital where these stories could be embodied as objects. In my head, it seemed like a good plan.

CS: I think it is valuable to clarify how this residency functions in relation to the services for patients and staff at the hospital. As far as I understand, Kings County has an impressive and robust creative therapy program with many art therapy professionals, one of the largest in the city. So, to host this artist-in-residence program in partnership with an international organization, I think something else is going on. What do you think?

MLR: Yeah, Sure. The Beautiful Distress residency program aims to give as much freedom as possible to the artists to explore in this environment. As you mentioned before, Kings County is a public hospital, one of the few in New York state that attends to clients regardless of their social condition, even if they don’t have health insurance or documents. It’s an institution that receives patients that are excluded from other health systems. For the same reason it has a very diverse community. Within this context they have opened a door for experimental art projects.

Let me explain a little bit more about how the residency functions. Kings County provides an apartment for the artist in the T building, a studio in the A building, and access to the Partial Hospitalization Program (PHP) in the R building. You receive an ID, and safety training, as any staff does, that grants you access to all these buildings. As an artist, you can organize your time and your activities as you would like to during the residency. There is encouragement to work with PHP clients or with hospital staff, but you don’t necessarily have to.

Since I wanted to engage with a group of people, the hospital facilitated access to PHP, which is a program for people with different mental health issues and diagnosis, who are going through an in-between phase. They come every weekday to the hospital, but then they go back to their homes. During the day, the participants get support through different kinds of groups, like group therapy, art therapy, coping skills groups, groups about learning to fill out job applications, etc. They also have lunch there. Many of the patients were previously hospitalized, so this program becomes a bridge phase before coming completely out of the institution. They still get some support from staff and are provided with extended access to therapy. The participants are starting to interact more and more socially, so there is more openness to do something. I remember somebody describing the acronym PHP, saying it could also stand for “People Helping People”

I found PHP to be a fascinating program because, in spite of the harsh experiences that everyone was going through, it was a learning group that provided a sense of community. As an artist-in-residence, you can visit the already existing groups or propose your own ideas to be part of the weekly activities. It seemed a big responsibility. I didn’t feel completely prepared to propose something. Everything was new to me, from the surroundings, the different buildings, and hospital bureaucracy to patients and staff.

CS: Let’s talk about your engagement with these groups. How did you start to get to know them? Was your first idea generating the kind of interaction you wanted?

MLR: I had in mind this “therapeutic bookshelf”, which included many steps and a rationalized plan. Once there, I discovered a major flaw in my plan; I simply couldn’t force a complex structure onto others to serve my project. I saw that every single patient, therapist, staff, and peer counselor had their issues. They were trying to solve very specific situations, many times in relation to an extremely complex environment and city. It seemed wrong to impose extra work of any kind on someone in the program. So I had to let go of my original plan, which was frustrating.

The first month I found myself living on the seventh floor of an administrative hospital building that was new to me. Driven by a chance encounter, I found myself there without a goal, and completely lost, which wasn’t easy. But it forced me to stop.

CS: Let’s dig a bit deeper to explore your experience going through this moment of transition. How did you start making connections that led to a fruitful project?

MLR: Looking back, the core of what I intuitively proposed is not that far away from what I did at the end, but it was created through a completely different process. It came more organically. I started by joining different PHP groups. I went to sessions where we would draw. I attended the pizza party on the last Friday of the month. I joined Reading is Fun, weaving crochet, and many other kinds of groups. I began learning how to participate. Everyone had their focus, as everyone does everywhere, so there were many different interests. I had to break my own stigma about mental health. It took a while to change my rhythm and not be anxious about what I was going to do. I needed to listen to what was happening, to hear the different voices contained in this building, in this hospital. I saw my position as an artist in this program as a very unique one; I didn’t have to rush, I could allow myself to be immersed in the place and all what it involved. Since there were already so many complexities, I realized I wanted to start with something simple.

At the time, I started to walk through New York City, going to different places outside the hospital. One day I was browsing at Mercer Street Books & Records, a bookstore in the Washington Square area in Manhattan. In the middle of some tables filled with some second-hand editions, I discovered a copy of I Remember by Joe Brainard. I’d known about this book for over ten years. I started reading it, and had an epiphany: “This is what I have to do! Start from writing!”

So, I initiated a new group that met every Wednesday. Using the same structure as Joe Brainard’s book, we wrote sentences, all starting with I remember. After we each wrote a memory, we read them out loud and then continued writing new ones. At the end of each session, for those who agreed, I kept the sentences in an archive. No participant was required to take part in any step. There were many things that some people didn’t want to do, and that was ok. This group was important; it transformed into a complex emotional and memory learning process that required openness and intimacy. It became my point of departure.

CS: So you started to build a rhythm through these Wednesday sessions. . .

MLR: Yes. I hosted the weekly session as a way of establishing a consistent thread to help us get to know each other. Patients were usually there for about six weeks. Each week, we would repeat the same activity again and again, week after week. Imagine yourself writing every Wednesday sentences starting with I remember. Sometimes people were bored by the repetition. I understood that it could become tedious, but this boredom allowed a kind of openness.

CS: Speaking of boredom, when I was a student studying ceramics at the Kansas City Art Institute back in the ‘80s, I heard John Cage give a lecture. I remember him suggesting that if you find yourself bored with what you are doing, keep doing it…then see what happens. This provocation made quite an impression on me at the time and continues to resonate. He suggested that boredom can be a productive state.

MLR: I’m used to coping with boredom.

CS: I sense that you are keenly aware of how your work connects to traditions and trajectories in contemporary art history, like the Fluxus movement and their use of scores. It didn’t surprise me that your ideas and experiences made me think about John Cage.

MLR: Ever since I was a student, I have had a relation to texts in my art practice. It wasn’t evident to me why I did it, but I always referred different artworks to certain books and made links between stories and my presentations. For instance, once I followed the Sakuteiki, one of the first historical gardening manuals, to build an installation. Now I can read that action as a score-based process.

What interests me about Fluxus groups is the action of erasing the boundaries around the ideas of where art comes from, who is making art, and where and when it happens. In that sense a score is very useful, it always refers to a process. I see this flow capable of freeing or blurring the rigid categories and exclusions contained in Western art history, cultural production, and its art institutions–to redistribute the role of artmaking. The Oulipo group in literature summarized it very well; by imposing multiple restrictions on the processes of writing they wanted to create tools for others to write. When you make art through a simple exercise that can be done by others and with others, then you recognize that anyone can be a valid interpreter of the score and a writer as well. I see Joe Brainard’s book operating the same way. Anyone can do their own I remember writing. It’s a very fruitful and generous tool. Here are a few of Joe’s sentences, so you can see how the format works:

“I remember that I put everything else on before I put my socks on.”

“I remember an ashtray that looked like a house when you put your cigarette down (through the door) the smoke came out of the chimney”

“I remember school desk carvings and running my ball point pen back and forth in them.”

“I remember walking down the street, trying not to step on cracks.”

What amazed me about these sentences is that they communicate everyday experiences that aren’t extraordinary at all. It’s a memory exercise that we all have done. Each I remember allowed me as a reader to imagine what I would say as a writer. This elemental writing exercise allowed me to expand my initial proposal from objects to sentences. Here are some examples from the I remember archive we made at PHP:

“I remember singing in the choir.”

“I remember finding $20 on the floor and being forced to split it up with my two friends.”

“I remember my first typing class, which was on a real typewriter and not a computer.”

“I remember a fellow student at college not knowing how a subway train can leave a station at the last stop.”

“I remember my first automobile, a Mercedes limousine. The first day I drove it on the freeway I was stuck by paparazzi.”

“I remember my first attempt at cooking, and oh my what a disaster it was.”

“I remember the first time I was called sir. It was in the college bookstore by a student approximately my same age.”

“I remember my mother telling the bus driver that I was younger than I really was in order to get on the bus for free.”

“I remember walking on a dock and hating the smell of fish.”

“I remember when a Hershey bar cost five cents.”

Sharing “I remember” stories can generate responses that have a physical effect. Like this one:

“I remember going to Coney Island. I was afraid of the rides. I wanted to get off, because I started to get an upset stomach. I remember I never went back on the rides again.”

When this memory of a visit to a theme park was shared, I immediately thought of the relationship that I have to a theme park. I could practically feel the experience. For some, it conjures a dream-like situation with vivid images like following the shape of a rollercoaster; for others, it is a real, concrete experience like having a stomach ache. One can also think about the language, the form of writing, or the sound of a word. Every week we were building a network of literary images; we were weaving connections and sharing them out loud.

CS: In addition to working with a group through PHP, what else were you doing?

MLR: All the stories that I’ve told you so far are related with the R building where PHP was. After the sessions or during the day I would take the elevator or the stairs and go to the A building. I was given a studio space that used to be a doctor’s office.

This is where I made other work and temporarily stored the collection of a museum that I have inside a hat; the Musée Légitime. I initiated this institution in 2017. It was triggered by an encounter I had in an art library when I was invited by Calipso Press to be in residence at “Lugar a dudas” [Place for doubts] in Cali, Colombia. While playing a game meant to reorganize the books in their documentation center, I came across a story on the 459th page of book 273. I found a short text that described an art gallery inside a hat called Galerie Légitime,which was created by artist Robert Filliou in 1963. This discovery served as a score to start Musée Légitime, which began by inviting artist friends to contribute a small or immaterial artwork that could fit inside a hat that I wear to carry around their pieces. Due to the lack of information that I could find about Filliou’s gallery, I began this reinvention with a lot of freedom and decided that my institution would take the form of a museum, to document and preserve the art pieces in its collection, and not replicate the commercial gallery scheme of the Galerie Légitime.

At the moment the institution has 118 pieces. I show the objects in formal and planned presentations as well as spontaneous situations. Sometimes I tuck a selection of artworks inside my hat and if the moment arises, I take it off and share the works with those around me. As part of activating the Musée Légitime, I pass around the different objects while sharing the stories that the contributors told me. This way, each person gets to hold the work in their hand and pass it to others while hearing about it. This interaction opens space for intimate attention with the items and their narratives.

Artists and friends that I invite continue to contribute because of proximity and familiarity with the institution. Now, through presentations, I have people starting to give me their stories and objects too. Also there have been donations of infrastructure in the shape of four different hats.

CS: Can you give a few examples of the stories and objects that have been given to you?

MLR: There are hundreds of them! It is difficult to privilege one over the other. Could you tell me three numbers from 1 to 118? Then I’ll tell you about those pieces in the collection.

CS: I love using a chance operation to explore the collection! Okay, how about 1, 54, and 68?

MLR: Oh! The piece number 1 is a bronze cylinder, very similar to a cigarette and it is called “Accompaniment.” You can feel its heavy weight in your hand. It is a contribution by David Bernstein. It is called something like “a smoking device for non-smokers in smoking situations.” The piece allows you to experience the act of smoking but without actually smoking. From my experience of his work, David really likes the idea of thinking with objects, he calls the process “thinging.” Piece 54 comes in a little box. It has a drawing around the box that specifies information as if it would be the coordinates in the archive of a classic museum. Inside there is a small sculpture made of paper pulp that resembles a bone of a little animal. The title of this piece is “Practical Zoology.” It was given by Rodrigo Arteaga who often works with hybrid pieces that seem taken out of a Natural History Museum (sometimes they directly are). Piece 68, donated by artist Nives Widauer,is the first extraterrestrial piece in the collection. It is a meteorite that came into the Earth through China. This tiny rock has a special feeling when you get to hold it in the palm of your hand. It is called “Spacecake.” Widauer has worked for a long time with meteorites in her art practice. A very good friend, who was a scientist, gave her the stones. One day, when I presented my museum at her home she approached me afterwards and said that she had something for my collection. It was the last meteorite she had from her friend that passed away a few years ago. Every night she went to sleep, afraid of losing it; it is so small. The day she gave it to me she thought that in the collection of my hat museum it was going to be better kept.

CS: Every time I experienced the Musée Légitime, you included the meteorite. It must have a particular significance to you too.

MLR: Well that’s pure coincidence. You didn’t know about the numbers of the collection, did you? I try to write down all the pieces that I present every time to keep records and maintain a balanced display of the collection. Of course there are pieces that become favorites and are shown again and again. I try to go against this by selecting other pieces, asking others to help me decide or by using chance techniques. But yes, it is inevitable that there are repeats.

CS: Lucky me! It was a remarkable experience to hold a tiny bit of another world in my hand.

MLR: I want to come back to your question about other dimensions of my practice and how they relate to what I was doing at the hospital. I was working on Musée Légitime, as I always do. After two weeks of being at Kings County Hospital it was evident that I had to show the museum to the group at PHP. I didn’t know exactly how, I didn’t want to bother anyone or produce an anxious situation. In previous impromptu situations, people got nervous when I suddenly revealed to have an art institution in my cap in the middle of a conversation. But one day I just brought it to an I remember session and I shared: “I remember two years ago I started a museum inside a hat. Do you want to see it?” I took off the cap I was wearing and started telling the stories of these different little or immaterial pieces one by one. That became a super interesting moment because it opened the possibilities of linking the act of remembering to objects.

Graylin Riley, a PHP peer counselor, kindly invited me to present it to another group. But this time we planned it together. He suggested combining Musée Légitime with performances by two other participants in the program. There was one patient who was very good at reading poetry. She didn’t write them, but she was an amazing reader. The other person was another patient who brought a huge speaker to the hospital every day. Nobody knew why he was carrying it because it was very heavy. Turns out, he was incredibly talented at lip-synching. So Graylin arranged different presentations that included Musée Légitime, introduced by a lip-sync show, then followed by a poetry reading, or the other way around. Afterward, we would give each other feedback.

CS: What was it about adding the process of feedback and reflection that was important to you?

MLR: I appreciated these exchanges a lot, they were encouraging for everybody. We were very excited about these presentations, and looked forward to them. I realized that mood plays a crucial role in any art production, and this exchange gave me confidence to do more presentations in other programs. I was invited by Tami Gatta, director of Peer Counseling and leader of Hearing Voices Network, to share the museum with one of her groups that was open to people and their families living with mental health issues from outside the hospital. These groups allowed each person in a family to be actively involved with the recovery of their relatives and somehow try to communicate what they were going through, which resulted in very emotionally intense gatherings. In this context the museum and its storytelling played a particular role. I saw it as an in-between act that allowed us to imagine something different from what was being said. It changed the focus of the conversation.

These experiences are difficult to describe since they were very much about the intimacy of the moment, but I can say that it shifted many preconceptions that I had about what I was doing. It broke stereotypes that I had about group therapy. Entering the residency, perhaps partly due to the plan I had to write to receive funding, I was looking for a result. I expected to have some sort of product, to extract something from the experience–to produce an art object. But I turned out to be in the middle of a collective transformative experience; this process changed my perspective. People don’t have to shape themselves for institutions but the other way around; the institutions have to be shaped around people. I realized that hearing these different voices affected me, which also directly relates to a piece I received for the museum by Ken Montgomery, Listen.

CS: I share your belief in the importance of listening and how crucial this skill was to your experience in the residency.

MLR: I was also amazed to discover situations that weren’t that evident at first. For a semi-nomadic institution, like the Musée Légitime, its transportability allows it to travel across boundaries that sometimes art institutions are not able/willing to cross. For example, there is a work by Sebastián Riffo in the collection. It’s a piece of solidified lava that he found in Japan in 2017. He describes it as a part of Mount Fuji. I think of it as the very texture of the mountain. One day after a presentation at PHP, one of the participants made an incredibly vivid remark. He said that he probably wasn’t going to have the chance in this life to go to Japan, so he thanked the Musée Légitime for allowing this material journey by touching the piece. Suddenly, I understood how special his imagination was. The tactile experience with this piece of Mount Fuji allowed a journey for all the ones who are able to imagine it. The same immersion feature could apply to three pieces of obsidian from the Alamo Canyon near Cochiti that artist Martha Tuttle gave me. She gathered them in the very same place where a friend almost drowned in a sudden flood. When she visited me the last day of my residency at Kings County, she added a moving story describing this experience and compared it to an eclipse. It is interesting for me to see how a particular story can reverberate with other experiences.

My head was filled with images from staying in a psychiatric institution, working with people, and dealing with so many different situations every day. I started to be overwhelmed with emotions and ideas; voices kept coming back to me when I was alone or asleep. The fact of living in a hospital brought an unconscious feeling of being imprisoned. It wasn’t the case; I could go wherever I wanted to, but at the beginning I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I had to do something to deal with these emotions.

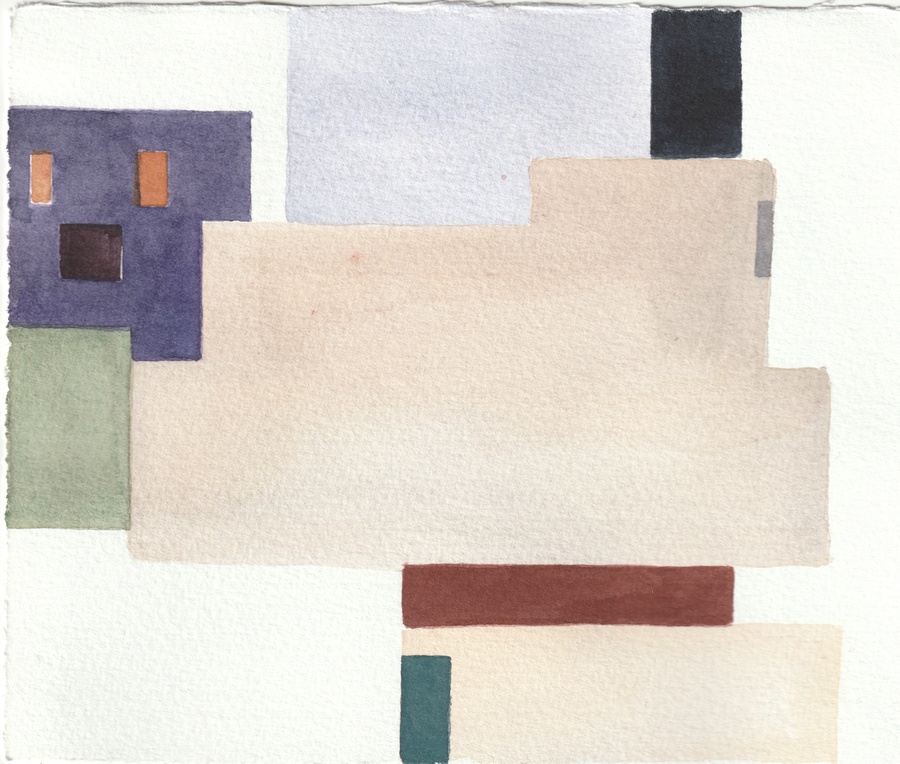

Reflecting on this condition also reminds me of a very particular memory from my hometown. I remember some little handmade cards, small crafted pots, carved wooden figures and small watercolors from the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos [Memory Museum and the Human Rights] in Santiago de Chile. These items that the museum calls artesanía carcelaria [prison crafts] were made by political prisoners in the 70s and 80s during their confinement in different concentration camps along Chile. When I saw these objects a few years ago I was very touched by them. They allowed the prisoners to resist and keep sanity during their incarceration that didn’t have a certain end date. I thought of the importance of doing certain daily activities that allow you to build an inner space when repeated over time, something equivalent to meditation techniques or physical exercises, but with an extra narrative component. This also applies to art and craft practices performed in less tough contexts outside imprisonment. I realized I needed to dedicate time to a personal practice during my stay in the hospital in the form of small, constrained exercises, to release, digest, and assimilate what I was experiencing. I started a daily practice of making a drawing of the kitchen window view from the apartment where I lived in the hospital. It became a crucial personal experience. It gave me a way of inhabiting that architecture and the atmosphere of the building. I played with my perspective of the light and the window view every time that I did a drawing. But mostly it allowed me to be surrounded by the experience without avoiding it.

It’s interesting to reflect on the experience of walking through the maze-like corridors of Kings County that connected the places where I lived and worked: the private studio in A building, PHP in R building, and the apartment in T building. I always took certain paths. After some weeks I began to notice the hallway bulletin boards throughout the campus. Carlos suggested that if I wanted to use a board he was totally keen on making it accessible. As my daily drawings started to accumulate, I thought it made sense to insert them in the daily flow of images in these passages. I pinned up a selection of drawings on a bulletin board in A building, to share this process within the hospital landscape. In contrast to the I Remember sessions, this was my intimate perspective shared with the staff that daily inhabited those spaces.

After work I would walk through Brooklyn or take the subway to Manhattan. I was always gathering city detritus that caught my eye. I remember picking up different objects such as a plaster cast ping pong ball, a turtle shape origami paper, the shell of a little colored egg found in a restaurant, two Japanese made reflectant lights for a bike, broken reading glasses, numbered birthday candles, white head matches, a collection of slides photographs of art historical pieces, a green exit sign, among others. I brought these things back and placed them in old hospital cabinets left in my studio. In all these encounters, the objects were loaded with the stories that I was hearing. These new collections allowed me to record and map my experience as this conversation does.

I also began to look through a collection of magazines, including old issues of Art in America and Artforum, that were left in the studio for the artist-in-residence to read or use. I started to make collages for another bulletin board in the hospital in the A building that was the closest to my studio and it was easy to manipulate. I was learning a lot about the language of these magazines and how they portrayed art in New York, and it was fun to cut and rearrange them. At one point I took the whole collage from the bulletin board back to the studio and realized that it could be arranged into a book. I made one and then continued making books, just shuffling and merging different art stories.

I knew that the PHP program had a library for the patients, which was mostly textbooks. I noted the lack of image-based books. From my studio experience, I had the idea to implement a new category for the PHP library–something closer to what we call artist books. When I asked Carlos for help to get some artist books, he brought me to Material for the Arts, an organization that distributes second hand materials to other social service and art organizations to use. He told me they had hundreds of books there. They were not exactly artist books, but more precisely books about art, old exhibition catalogues, and art history books. I came back with around 50 or 60 of them. It seemed odd to just place them at the PHP library; I found myself reluctant to do so. Instead, I shuffled them, cut pages, made inserts, took titles and sections out. So, in the end I started a collection of my own artist books for PHP. I called the new category “Icaros” in honour of the medicinal songs sung by Shamans healers in the Amazon jungle. I was exploring different possibilities to work in this particular environment, planting future encounters, even after I left.

CS: Your use of collage that led to the artist book intervention makes so much sense–giving yourself a rule to begin a pattern of actions. In turn, this process generated other ways to make and remake from the materials and everyday rituals that shape a place, whether that is a hospital program, a studio practice in a unique location, or exploring a new city. Does that make sense?

MLR: Yes, it does. I believe that sometimes a minor change in what you called everyday rituals can make a bigger shift in a whole pattern of behavior.

CS: I am curious about where you find fertile territory for your work at different stages of making and sharing a process with others. What are some of the methods that you use?

MLR: Well sometimes I just follow certain paths of action. For instance, another project called “Gamma Colors” that I performed in my studio circled back to PHP when I proposed at the end of every Wednesday workshop to rename paint color charts, those you take as samples for painting your home. I found these industrial paint color charts in Amsterdam in a store called Gamma with very weird names. For example, a strong yellow color was named Kaas [cheese], a Calypso color called Protest [Protest] or a light mint green called Sokken [socks]. Some names were very random, others were loaded with meaning and cultural associations like one dark blue that was called politie (police), a terracotta color that was called museum or a dark brown that was called indiaan (indian). I showed them in the workshop, translated them and then invited everybody to put our own names to the colors. It was a very simple exercise that allowed many words and free associations to come out. We renamed many Gamma colors: Lucid Dreams, Sandy Ice, It’s a Cold!, Baby grass-Mama grass-Daddy grass, Black Lives Matter, Voices, Anxiety, BTS, are some of them.

I feel that every single art experience somehow owes itself to other experiences. To recognize something as art, a previous code is needed to get access to it. Despite the encounter one can have in a moment, it is integrated in a network of relationships that is always in the process of being. Sometimes I don’t understand this about my practice; maybe it is too close, too familiar, I repeat certain basic habits without even realizing it. But when I became an alien in a foreign environment, I had to acknowledge that I was continuing, in a particular way, some practices I learned from my family, from certain traditions that were inherited. There are many knots in one’s stories that need to be unraveled in order to understand the patterns that conform our behavior.

Now, I see my role as an artist working in a hospital, as someone who had to give shape to a practice in relation to that immediate reality.

CS: What else?

MLR: There were other connections I made at Kings County not just related to PHP. For instance, one day Carlos asked me to share what I was doing at the hospital with the Community Advisory Board and Behavioral Health Committee at a monthly meeting. He saw it as a possibility of giving visibility to what was being done in the residency. Sometimes there are so many issues in a hospital of this size, that this sort of program could go unnoticed by the administration.

This session was very official with a secretary that wrote down all the proceedings. There was an already defined agenda, with only a short time allocation for me. I proposed to host a quick “I remember” exercise. I also wore the museum, in case there was time for it. I felt it was important to be able to treat these different contexts in a similar way.

Before I introduced my practice, there was a report about a ligature risk prevention program. I got nervous by this previous topic, but continued with my presentation. I expected sober participation. To my surprise, the exercise was received with excitement. It became a joyful disruption in the rhythm of the meeting. This spontaneous reaction made time to share Musée Légitime. My intervention was followed by a discussion about the therapeutic quality of the “I remember” exercise and the act of storytelling. I insisted that I wasn’t trained as a therapist but if these exercises resulted in some relief or self-awareness that was a great outcome. Carlos and I were particularly interested in this point also to show how artists could contribute to the hospital in a different register, not just repeating the already employed clinical techniques.

CS: Thanks for sharing this experience, it starts to answer the earlier question of what is distinct in offering the Beautiful Distress residency. I also want to discuss how your work and these socially engaged projects find visibility in a contemporary art context. You mentioned going out and around and bringing the Musee Legitime with you as a bridge for getting to know other artists. Would that be a fair way of describing how you activated the museum as a way to make connections?

MLR: Yeah, totally.

CS: And what did you find?

MLR: During my stay in New York I encountered different social networks and carrying this little institution in a hat opened access to these very different realities, people and their stories. The museum became a trigger for deepening connection with different people I met. For example, I met you at a cocktail party. Maybe if I wasn’t wearing the hat that day nothing would have happened.

CS: It’s true, experiencing the museum increased my interest in getting to know you and learn more about what you were doing.

MLR: I also had presentations in spontaneous locations. For instance, I had a very moving presentation for the Day of the Dead at a place called Luncheonette, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Marc Buchy, an artist in the collection, suggested I go there. It used to be a diner that was transformed into a social center for artists in the neighborhood. This was done to honor the wishes of its former owner, who everyone called B. She had passed away one year ago. My presentation was part of an event that commemorated her legacy and ongoing struggle for a shared social space. The organizers asked visitors to remember someone who passed away. Since I was wearing the hat, and after hearing the stories about B, it felt proper to tell this story that owed itself to people that weren’t here anymore.

There were other in-between moments too. I also made a connection with the Water McBeer gallery, which specializes in miniature artworks and dollhouse-like exhibitions. Ignacio Gatica, a good artist friend living in Brooklyn, triggered it by making a video work on a little screen with two copies. He gave one of them to Water McBeer and the second to the Musée Légitime.

I went to see an exhibition where the piece was being shown: “The private collection of Water McBeer” at Deitch gallery. The little screen showed a newsreel that described the tallest skyscrapers in the world. This list of high buildings served as a bridge to contact both micro art institutions. I called McBeer, to show him the Musée Légitime. It was exciting to explore the arts ecosystem made between a museum and his art gallery. After a fruitful exchange of views and plans for the future, Water MCBeer became a donor of the hat institution. As he said; “For a smaller museum, donors want to feel a greater sense of involvement than with a large institution and it is important that they can see the impact of their funding in a visible way.”

From the 17th of June until the 29th of July, 2019. Courtesy of the gallery

CS: During this conversation, I wrote down a few words and wondered how they might resonate with you: Storytelling, Remembering, Intimacy, and Secrecy. Depending on how they are combined, the interplay can open doors into intimate, vulnerable, and powerful emotional spaces or really difficult experiences.

MLR: It is interesting that you chose those four words. They are an accurate approach to what I experienced at Kings County. We have talked about storytelling, memory and also about the importance of being able to listen. I don’t think that we touched much on secrecy. Maybe when I talked about my father’s practice and the cabinet. I appreciate this word because it refers to something that it is difficult to talk about. A sense of the unspoken was often present during the residency and I think it always exists to some extent. There were often situations at PHP that were very meaningful to experience but needed to be kept confidential. To build an intimate space, it is important not to communicate everything. In that sense there is a dimension that is missing and that can’t be transmitted.

I’m very thankful for the staff and patients that trusted me and the process. Giving time and patience for creative experimentation was quite generous in this context. I appreciated the mutual transformation and openness. I think that making time for a shared practice or a conversation can be very transformative.

CS: Before we wrap up, let’s reflect on Beautiful Distress, and their focus on addressing and dismantling the stigma around mental illness through art. While you didn’t have a specific policy mandate, I think there was a shared interest regarding social conditions that need to be changed, that perpetuate the shame and stigma around mental health struggles. How might your residency be part of addressing this?

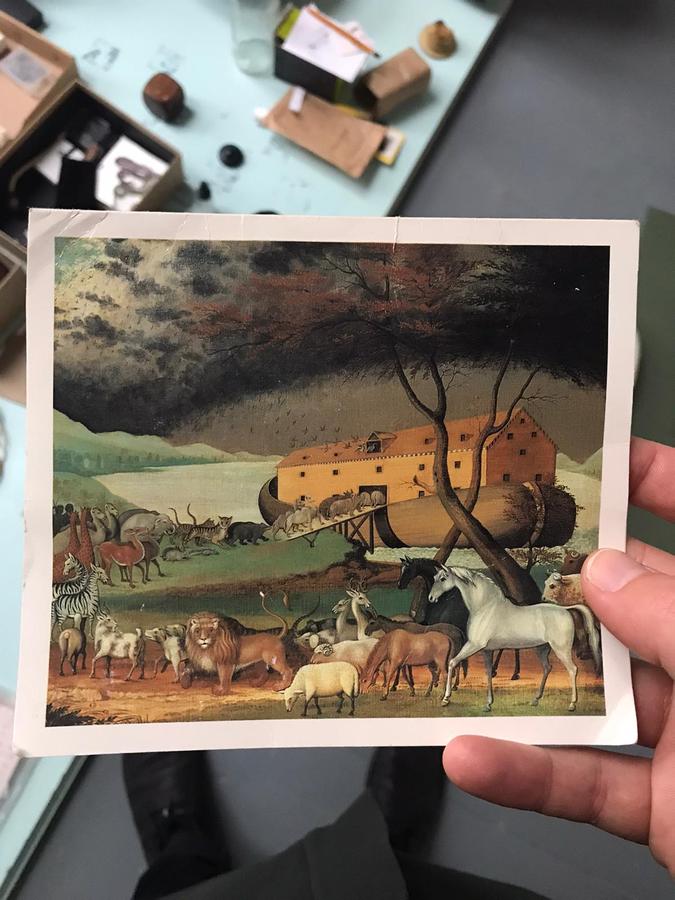

MLR: At Kings County I experienced a complex territory but at the same time a very fruitful one for an experimental and shared art practice. I feel that communicating these experiences to others, through different networks outside the hospital can be a good tool for breaking stigma. Talking about it as we do now can be a good start. It demands sensitivity and care, but is not impossible. The documentation will never be the same as the lived experience, but it can be a memory mechanism that allows you to come back to the process that was done. The focused and simple exercises allow translation and reproduction. Certain participants wanted to preserve their anonymity which is an initial condition for joining PHP groups. At the same time, everyone agreed that the work created and archived in this PHP group at Kings County Hospital could be publicly presented under a collective name. Honoring the group’s privacy becomes a challenging and motivating factor for thinking about how to present and unfold this kind of artwork. On the other hand, some participants at PHP wanted to be acknowledged. For instance, I received a piece by Timothy Dabriel that was meant for the Musée Légitime. He gave me his piece one day that I handed out a collection of postcards with the motif of Noah’s ark after starting the session saying: “I remember when I was a child I used to play with a puzzle with the image of Noah’s ark and the animals.” He took one of the postcards and made a drawing of the missing Noah, on the opposite side. Then he approached me and explained he had something for my institution. Till that moment I hadn’t invited anyone in PHP to be part of the museum. When I accepted the piece, Timothy referred to the museum in the hat as an equivalent of Noah’s ark. He also wrote a story about it:

“I remember when Noah save the animals from being extinct. He built a ship for them to make them safe when the water raise. Everyone thought he was crazy, but he proved them wrong. Then everyone started listen to him. I remember being happy to see him save the day, Noah is a great person. I like to meet him; he is a big inspiration.”

I was particularly touched by this story.

CS: Now I am also touched by his gesture and story. Something I have learned about your creative practice– you invite others to connect through sharing memories, even if they weren’t there during the initial encounter, to extend and deepen connection.

MLR: I agree, we can remember and imagine through others’ memories. That is why it is so important to exercise it. Each object, each story can also be a germ for something else to happen next. In that sense my aim is to display and reproduce the material from the exercises that we did at Kings County to carry these stories and keep telling them.

I found a fertile territory at Kings County hospital in the space between writing and image making. Just as in an ekphrasis, that is a verbal description of a visual representation, the objects in the therapeutic bookshelf were replaced with sentences. The same happens the other way around, with stories that become an object in my museum.

I have continued with “I remember” sessions outside the hospital, with one experience in Santiago at the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, and another one at Beautiful Distress House in Amsterdam. I am working with writer Mirthe Berentsen, who also did the Kings County residency in 2017. We are exploring the transformations that we both underwent in our practices within a hospital context and thinking about how to make an exhibition that can translate these experiences outside the safe space of group therapy in a public sphere.

I see this work as an ongoing edition. In order to continue with these processes some things need to be included and shown while others kept in the intimacy of what it was. Someone told me, “I remember nothing, I’m in the present now.”

Carol Stakenas is a curator and educator. Her work is deliberately varied, generating opportunities for people to come together and respond to timely issues in meaningful contexts through art. She has commissioned and supported boundary-breaking work by diverse artists and collectives including Cassils, Mel Chin, Fallen Fruit, Jeanne van Heeswijk, Suzanne Lacy, Marjetica Potrč, Raqs Media Collective, Ultra-red, Denise Uyehara with James Luna, and Marina Zurkow. She has produced projects at sites including the Brooklyn Bridge Anchorage, Times Square, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), Kings County Hospital in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, and the Story Mill Grain Terminal in Bozeman, Montana. Stakenas is a curator at-large for the Social Practices Art Network (SPAN).

Martín La Roche (Santiago Chile, 1988) is an artist based in Amsterdam. He studied Visual Arts at the University of Chile in Santiago and then in 2015 he completed a postgraduate program at the Jan Van Eyck Academie in Maastricht, the Netherlands. In 2017 he started the Musée Légitime, a nomad institution that now has 118 artworks by different artists in its collection. He is also involved with different artist publishers, brought together in his Good Neighbour practice; an artist book platform that builds a library through affinities between books. Lately his work has been shown at Die Ecke Arte Contemporani, Barcelona, artspace Edition Shimizu, Shizuoka City, Japan, Water McBeer, New York, USA, Muro Sur – D21, Santiago, Chile, Casanova, Sao Paulo, Brazil and de Appel, Amsterdam, The Netherlands among others.

Beautiful Distress art-in-residency program is held in collaboration with the Behavioral Health Service of the Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. This residency received support from the Mondriaan Fonds, the Netherlands.

También te puede interesar

David Batchelor.colour, City And Culture

David Batchelor (1955) is a Scottish artist based in London who has been working on colour for 25 years. Last December, I had the chance to go back to London and, because of my...

SIGFREDO CHACÓN: SITUATIONS. EARLY WORK, 1972

Miami Biennale y Henrique Faria Fine Art | New York presentan "Situations", una recreación de la instalación del artista Sigfredo Chacón (Caracas, 1950) presentada originalmente en el Ateneo de Caracas, en 1972. Desafiando la...

EDGAR CALEL: B’ALAB’ÄJ (JAGUAR STONE) [PIEDRA DEL JAGUAR]

By recovering collective processes of meaning-making linked to the place of belonging, the exhibition calls for the persistence of a present that reverses the neoliberal logic of economic concentration and hyper-individualism. Instead, it offers...