THE ROLE OF ART IN TIMES OF PANDEMIC

This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.

Torri Morrison

Our main job as artists is to make the art that only we can make, right now in the times in which we are living.

Allison Smith

During these strange days, a lot has been said and written about the importance –even the necessity– of art amidst this sanitary, social, and economic crisis. A quick reading through newspapers and magazines, both national and international, leads to boastful, demanding, and glib phrases. “The artists are the only ones who cannot be silenced”, “art will save us”, or the headline “The art standing up to Coronavirus.” Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the vast majority of people who make those statements are not artists. How did we get to the point where we demand so much? How did we imagine that a very informal sector could “stand up to” a virus?

The obsession with giving a tangible utility to art dates back to the Thatcherism and its obsession with the economy in the 80’s, when the Arts Council England commissioned John Myerscough to write a governmental report about the economic importance of arts. This introduces a considerable change in public cultural policies: gone are the days in which arts were considered for its cultural value, or as civilizing and educational tools. The Myerscough’s report argued that arts should fund themselves by virtue of its economic value, so it starts to make funds delivery for cultural initiatives conditional to the social impact of each work or project. The question becomes how much capital they can generate, how many jobs they can create, how many slums they can reform. Female artists had to demonstrate their utility in order to be funded by the State, either by making something to reduce alcoholism, prevent crime, or contribute to mental well-being, social cohesion, and national unity. In a society obsessed with the economy, this was easy to understand for fanatical governments of fiscal austerity; in such situations, the only way to justify art is considering artists and artworks as tools for economic and social development.

More than 30 years have passed, and the Myerscough’s ideas remain, both in Chile’s public policies and our collective unconscious. Nowadays we consider the artist, even without noticing, as a commodity of this society of entertainment: a product ready to be consumed, digested, and forgotten, moving quickly to the next one. An extractive cycle typical of our own neoliberal system, where the resource to be exploited is the very person. It is the argument behind demanding therapeutic or relaxing qualities from art, a distraction for busy people who have to produce. It is already discouraging enough when art gets reconfigured as a tool to increase the productivity, just as the thermostat of an office gets reconfigured at a certain temperature to make people work more time and more focused. It is even more discouraging to see artists being forced to those performances, which are many times necessary to get a further financial benefit. We constantly demand and interrogate artists, feeding that insatiable hunger of “contents” (that endless cycle of 24/7 news) typical of the attention economy; and simultaneously, we transform the artist’s idea in an absolute category, in which one is easily interchangeable for the other one, and remove all those significant differences at the moment of creating art, both socially (race, class, sexuality, ethnicity, genre, age) and personally (interests, processes, models, media).

It is not unimpressive that the vast majority of artists still live in an unknown deep job insecurity. Almost 60% of people’s incomes are lower than $501.000 Chilean pesos; one third of the population is the sole financial supporter of their household; 85% of people have lost their jobs because of the COVID-19 crisis; and 81% of people cannot take sick leave because they do not have a contract [i]. And yet many people do not understand that artists survive the pandemic just as everyone does: anguished, scared, and tired. With good and bad days. Feelings that probably have got worse because of pursuing a very precarious profession, and in which asking for help has a strong disapproval. Conventional wisdom says that you are responsible for having chosen a creative career -if you took the risk despite the dangers, the only one you can blame when something goes wrong is yourself. It is part of a neoliberal discourse that appeals to an eternal personal improvement, in which every failure is the outcome of not having tried hard enough, of the meritocratic dream in which “where there is a will, there is a way”, “early bird gets the worm”, or that disdainfully responds to “why don’t you organize a bingo?” (a controversial question asked by a Chilean politician as a response to people who were demanding better infrastructure in schools). It is an extremely individualistic philosophy, in which the systematic failures are hidden, and the burden falls squarely on the shoulders of individual responsibility.

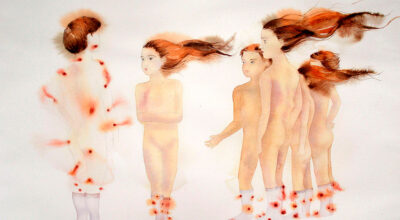

There is still the romantic notion of the artist as someone eccentric, visionary, even mystic, that climbs its ivory tower and descends imbued with visionary ideas. It is an image closely related to an idea of the “universal” artist, in other words, a white middle or high class man with the privilege of strolling, thinking, giving his opinion -of being a flâneur who walks freely around the metropolis, immersed in his worrying without more responsibility than that. In the last decades, cultural studies as well as feminist, queer, and antiracist thinkers have begun to deconstruct that one-dimensional view of what to be an artist is. It has been possible to think and give space to female, black, excluded artists; to artists of sexual dissidence, migrant artists, indigenous artists. Society groups that, incidentally, can rarely focus on being “full-time curious”, either because they take care of the house, of a beloved one who is bedridden or sick, of children, or because of the impediments created by racism, male chauvinism, or classism.

Undoubtedly, art has a lot to say these days. There are people who focus on the “art for art’s sake”, prioritizing the technique and pushing the limits of plastic art, creating beautiful objects that invite us to contemplation, stop, and rest. Other people focus on a more conceptual or political art; they will undoubtedly develop necessary works, dreaming new imaginaries and facing us with our failures. Let’s think about the great structural problems, so standardized until a few months ago, that this virus has forced us to look at: as the inequality and its impact on the health quality to which we have access, the work-from-home option, and even the possibilities that a home can offer as a safe space. Or the fragile economy, and the radical difference between the real economy and the so respectable world’s stock exchanges. Even the painful preference of certain sectors for a strong and practical economy, although that means to condemn others to disease and death -the utilitarianism and the worship of progress taken down to the last consequences.

To expose these ruptures, to create objects worth contemplating, artists will need time, light, water, and stability. They will need to get involved in long, thoughtful, experimental processes; being able to assemble and disassemble, to dream and lose hope, in order to achieve the perfect formula. Requiring immediate answers (beyond an opinion or a personal intuition) to a highly informal sector is grossly unfair and totally blinded. Crisis are not, at least as long as they spark off, educational opportunities. They are events that occur and hurt us. They indicate everything about us, included our learning and reflective abilities.

Undoubtedly, art can collaborate in many areas of human jobs. However, its main value is its ability to humanize us. Art cannot necessarily change behaviors. It is not a pill or a class. Empathy is not developed by just looking to a painting: it implies a work, work for which art delivers the materials. It cannot win an election or overthrow a president; it cannot stop the climate crisis, cure a virus, or bring the dead back to life. Nevertheless, it is an antidote in times of chaos, a roadmap for greater clarity, a force of resistance and repair, creating new records, new languages, and new images to think about. It is a slow tool, which does not act immediately, but demands experimentation, continuous analysis, deconstruction of stereotypes, and thinking patterns. “Art has other tasks: not to explain, call to action, not to become an alternative journalism or cultural diplomacy. Our methods may be unpopular and hard, but in order to deconstruct something, art must move away,” Lesya Khomenko comments.

These are tough days. Artists in need of income promote themselves as they can; museums and galleries broadcast day and night about the transformative power of art, its ability to redeem and guide us on dark days. Big shows, theater, dance, musical events, and art exhibitions are being canceled worldwide. Although the consequences are important for major institutions and the tourist industry, smaller organizations and independent artists will be the most affected because ticket sales, international residences, and public funding will run out. Probably, many people will have to look for a more lucrative job. We should take into consideration the precariousness of our cultural and artistic institutions, and work to support them, because even the most famous and successful institutions usually operate on margins that would surprise those who do not work in the cultural sector.

I would like to come back to the necessity of answers, solutions, notifications. Nowadays, many people can enlighten us, share their thoughts, and give advice. Let’s consider the thoughts of medical staff in clinics and hospitals, putting at risk their lives and the lives of their loved ones day by day; people picking up the trash of our homes every week, invisible and marginalized; those crossing town by public transportation to ensure the livelihood of the ones who can actually work from home. All of them have something to say, ideas to express. This virus in an opportunity to listen to the voices of people we typically ignore. At the same time, it is important to recognize and protect the work of our artists. The best things are generally delicate, and the fact that they are not clearly useful is not an argument against their value, but an argument in favor of taking care of them and protecting them. Spinning the straw of anxiety and fear into gold is possible. However, it is an extensive search that will require effort and support.

Art is an essential tool to provide us with a sense of perspective. Nonetheless, it does not happen automatically. We live in a time marked by the obsession with new and original. But truth is that the problems we had to face because of this virus were already there since one, two, or five years. If we look for answers, there is a series of works that can enlighten the questions that today bother us. A year ago, in Venice, Voluspa Jarpa argued against the colonial mentality that we cannot get rid of yet. Cecilia Avendaño with Enfermedades Preciosas forced us to think about the pain, the feminine, the violence, and the beauty. Or Carlos Arias, who already warned us about the limitation of binarism in the public speech, coming ahead of the polarization of the following months. These and many other artists have been straightening out pieces of a society that is falling apart; they need our help today, either personally or institutionally.

Artists are explorers, healers, activists, and visionaries. Making art is essential to speak truthfully to power, to dream with new realities, and ultimately to change the world. It is possible, even in quarantine. I think about Frida Kahlo, who made her first portraits confined in her bed, recovering from that tragic bus accident in which her body was severely injured. I think about the indigenous traditions of telling stories, I think about media arts, so contemporary not only in their message, but also in their medium; and the thousands of ways in which humans trust in artistic representations to make sense of changes and crisis.

For a long time, we have required artists to navigate a complex web of structures, relationships, and arrangements, either globally and locally, most of the times for little or no payment. Something that begins in the studio as a creative practice, mostly in solitary, depends on a thriving visual arts sector and also on audiences, relationships, and contacts. When these get suspended, the ability to maintain the creative practice is suspended too. Instead of asking and demanding, let’s question the ways in which we can contribute to transform that way of working, so we do not have to normalize again the image of the artist who lives with a chronic insecurity, under- and over-employed at the same time, always thinking about the next project to stay afloat.

May these times of distance and over-connection show us, more strongly than ever, that duty of care we have to our artists as a society.

Traslated by Constanza Figueroa

Spanish version here

[i] Plataforma de Artes Visuales, first survey “Impact of the Covid-19 health crisis on the workers of the visual arts in Chile.” Carried out between March 20 and 25, 2020. Available at https://media.elmostrador.cl/2020/04/PAV-2020-Catastro-Coronavirus-primero.pdf (in Spanish)

También te puede interesar

ARTE, SALUD Y CONTEXTO. EN KIOSKO GALERÍA, BOLIVIA

Las obras de la exposición online "Salud" giran alrededor de tres puntos que se combinan entre sí: el problema médico, el humano y el político. Con la participación de 22 artistas latinoamericanos que respondieron...

MANUEL SEGADE Y EL CA2M DESPUÉS DE COVID-19

"Nos parece muy necesario desautomatizar el proceso reciente de digitalización de nuestras relaciones y de desaparición de la posibilidad de poner nuestros cuerpos juntos: necesitamos reconstruir nuevos rituales, nuevos circuitos que permitan formar nuevas...

ARTE AL FONDO, O NUEVAS PRÁCTICAS DEL HOGAR

Creo ciegamente, que esa responsabilidad de tomar una pausa, de repensar todas las direcciones, de valorar todo aquellos que está fuera del marco de representación y es invisibilizado en los medios dominantes, es en...