Paz Errázuriz: Próceres [National Heroes]

If we are to extract a lesson from the relearning of memory that bodies and languages had to practice in the Chile of forgetfulness [de la desmemoria, “disremembering”], it is knowing that the past is not a time irreversibly seized and frozen in recollection under the rubric of what already was, thus condemning memory to follow the dictum of obediently re-establishing its continuity. Instead, the past is a field of citations, crisscrossed as much by continuity (the various forms of supposing or imposing an idea of succession) as by discontinuity (by cuts that interrupt the dependence of that succession on a predetermined chronology).

Nelly Richard

By Rebecca Jagoe The past is never simple. It is never linear, singular, or teleological. Yet as we often hear, history is in the hands of the victors, and those victors will often shoe-horn events past into a streamlined narrative: they will render it singular, and anything that might contradict this may be cropped out, erased, destroyed. Through-out the twentieth- and into the twenty-first century, fascist and far-right regimes have deployed historical and cultural negationism as a means of forwarding propaganda, a false justification for state-enacted violence and genocide. This was no less true when Pinochet rose to power through a military coup in 1973. Throughout the regime, tens of thousands of people across Chile — and there is no consensus on figures — were tortured, exiled, killed or ‘disappeared’, and all done so without any record or documentation, destroying both lives and memories. The reasons were both manifold and the same: whether it was for political dissidence or political belief, identity or indigeneity, anyone who did not fit into the regime’s narrow parameters for citizenship was a possible target. 1973 also spelled the start of what Soledad Bianchi referred to as the ‘apagón cultural’: cultural blackout: a funda-mental tenet of historical negation. All forms of cultural production which could not be streamlined into propaganda for the violent fascist regime were censored and oppressed, and many artists, musicians, intellectuals and writers were deemed dissidents, and faced exile, arrest or murder at the hands of the militares. [/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=»3.2.2″ src=»https://artishockrevista.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CONTAGIO_37_s.jpg» show_in_lightbox=»on» align=»center» alt=»Installation view ‘Próceres %91National Heroes%93’, by Paz Errázuriz, at Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, 2020. Photo courtesy of CBP» title_text=»Installation view ‘Próceres %91National Heroes%93’, by Paz Errázuriz, at Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, 2020. Photo courtesy of CBP» /][et_pb_text _builder_version=»3.2.2″] Against such a backdrop, Paz Errázuriz, a primary school teacher from Santiago, decided to take up a camera. For Errázuriz, photography and resistance began at the same time. Working as a family portrait photographer by day, she was also using the camera to document people who were marginalised and forced into the periphery: sex workers; psychiatric patients; protest groups. With her house raided in 1973 by the police, she was perpetually mindful of the need to work within the boundaries dictated by the state, as the only real means of being able to continue this mode of resistance. She was constantly treading the lines of censorship: as the artist stated in an interview with Dazed: ‘The need to photograph was a constant, but one had to be extremely careful’. With a practice that was protesting both covertly and in plain sight, her sensitive portraits brought to the fore subjects whose communities were being rendered invisible, and whose lives were most threatened. It is these works for which the artist became known: first, in Chile, and then to an international audience, with her cofounding of the Chilean Association of Independent Photographers [AFI], which allowed her to position herself as both artist and reporter. Errázuriz describes each project or body of work as an ‘essay’. This particular essay, National Heroes, was taken in 1984, but remained a box of negatives that were kept in the artist’s closet until she printed the images in 2019, when they were shown for the first time in Montevideo Uruguay. They have never before been exhibited in Europe. At the time the images were taken, Errázuriz was working in a foundry which produced was producing monuments for the military. She began photographing fragments of statues which were the useless remnants left over from the process of casting: failures, excesses, the surplus that was the inevitable collateral of production. These parts — dismembered limbs, sections of bodies, or faulty wholes — lie prone, humbled, sometimes wrapped in blankets. When speaking of the series, the artist highlighted that ‘heroes’ is ‘a word that in Spanish only exists in the masculine form’. The images may seem at first to be a departure from the work for which she has become best known, with their complete absence of human subjects. And yet, in showing the messiness, the uncontrollable excess, that must lie behind the creation of these ‘heroes’, Errázuriz was highlighting the impossibility of creating a clean, purist, singular narrative of history, and, further, suggesting the human cost which lies at the heart of this manufacture of propaganda. Too often, the act of memorial is less an act of remembrance than it is an act of forgetting. As Milan Kundera writes, ‘The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have somebody write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history.’ [/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=»3.2.2″ src=»https://artishockrevista.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CONTAGIO_38_s.jpg» show_in_lightbox=»on» align=»center» alt=»Paz ERRÁZURIZ, Untitled, 1983, Digital printing. 12 Pigmented inks, on Canson Infinity Baryta paper, 36 x 46 cm. Edition 2 of 6. (Printed in 2018). Courtesy of CBP» title_text=»Paz ERRÁZURIZ, Untitled, 1983, Digital printing. 12 Pigmented inks, on Canson Infinity Baryta paper, 36 x 46 cm. Edition 2 of 6. (Printed in 2018). Courtesy of CBP» /][et_pb_image _builder_version=»3.2.2″ src=»https://artishockrevista.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CONTAGIO_39_s.jpg» show_in_lightbox=»on» align=»center» alt=»Installation view ‘Próceres %91National Heroes%93’, by Paz Errázuriz, at Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, 2020. Photo courtesy of CBP» title_text=»Installation view ‘Próceres %91National Heroes%93’, by Paz Errázuriz, at Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, 2020. Photo courtesy of CBP» /][et_pb_image _builder_version=»3.2.2″ src=»https://artishockrevista.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CONTAGIO_40_s.jpg» show_in_lightbox=»on» align=»center» alt=»Installation view ‘Próceres %91National Heroes%93’, by Paz Errázuriz, at Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, 2020. Photo courtesy of CBP» title_text=»Installation view ‘Próceres %91National Heroes%93’, by Paz Errázuriz, at Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, 2020. Photo courtesy of CBP» /][et_pb_text _builder_version=»3.2.2″] Errázuriz chose to print these photos for the exhibition, in direct response to the political unrest in Chile, of a level that has not been seen since the toppling of the dictatorship in 1990. Whilst the country’s economy has, to all appearances, flourished in the last 30 years, it is a neoliberal agenda of privatisation which has motivated the economic growth, with a growing disparity between the extremely wealthy and those living in poverty. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has stated that 1% of the population own 26.5% of the nation’s wealth, and 50% of low-income households access only 2.1%. And yet the official line continues to be one of national success, economic boom: negating and overlooking the inconvenient truth that so many people across the country have been living in increasing precarity. At the beginning of November 2019, Mapuche protestors in Temuco decapitated the statue of Chilean military aviator Dagoberto Godoy, hanging the head from the statue of Mapuche warrior Caupolicán. Quoted in The Guardian, Mapuche writer Pedro Cayuqueo stated that ‘These are actions of a very potent symbolism, in rejecting an official version that has falsified and grossly airbrushed our history’. It is clear that this 2019 toppling of this military ‘hero’ is an act of revision which highlights the violence that has been perpetuated against indigenous communities over the past 150 years across the country. In its dominant placement as a figure of remembrance, it came to represent the erasure and ‘forgetting’ of this violence by official narratives, even since the fall of Pinochet’s regime. This statue, alongside many others across Chile, was not the symbol of military supremacy: it had come to stand for the silencing of entire communities, the violent marginalization of indigenous groups, and much more besides that. Nelly Richard has written that since the toppling of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, ‘the figure of memory has most strongly been dramatized by the un-resolved tension between recollection and forgetting’. The statues being toppled across Chile have become figureheads not of heroism, but of this tension. Seeing the photos of the toppled icons alongside National Heroes, underlines that this tension between erasure and reality has perpetuated at every stage of the statues’ existences, even at their creation. Errázuriz, in documenting these moments, and in choosing to exhibit them at such a time, is highlighting that while a ruling power might attempt to create a singular narrative of might and strength, it is impossible to control the narrative that exists in the collective imagination: it is impossible to erase other narratives. The regime may have wished that these statues represented the supremacy of their militant rule, but there is always more meaning that is attached. These photographs are as relevant now as they were when they were first taken: perhaps even more so, for their ability to serve as a potent reminder of what lies behind the writing of history. The past is not a singular narrative, and must be remembered in its multiplicity: it cannot be the so-called victors who write the terms of what is retained. As Alexia Tala wrote of the series, ‘what are those ‘residues of heroes’ but a questioning about the manipulation of historical processes?’. [/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=»3.2.2″ src=»https://artishockrevista.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CONTAGIO_43_s.jpg» show_in_lightbox=»on» align=»center» alt=»Paz ERRÁZURIZ, Untitled, 1983, Digital printing. 12 Pigmented inks, on Canson Infinity Baryta paper, 36 x 46 cm. Edition 2 of 6 (Printed in 2018). Courtesy of CBP» title_text=»Paz ERRÁZURIZ, Untitled, 1983, Digital printing. 12 Pigmented inks, on Canson Infinity Baryta paper, 36 x 46 cm. Edition 2 of 6 (Printed in 2018). Courtesy of CBP» /][et_pb_text _builder_version=»3.2.2″]Paz Errázuriz: Próceres [National Heroes] is on view at Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, until 6 March, 2020. This is the first Viewing Room exhibition at the gallery and the first public showing of this series of works. [/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

También te puede interesar

CARÁCTER 2018. MUESTRA DE EGRESO DE LA ESCUELA DE ARTE UDP

La Escuela de Arte de la Universidad Diego Portales (UDP), en Santiago de Chile, presenta hasta el 18 de enero la muestra Carácter 2018, que como cada fin de año académico reúne en el...

BLENDEN: LA PIEL DE LA ARQUITECTURA CAPITAL

La transformación de esa arquitectura habla no solo de una forma de protección, sino también de un aislamiento, de una capa impenetrable, de una negación del mundo. El sistema, paradójicamente, aparece aquí como la...

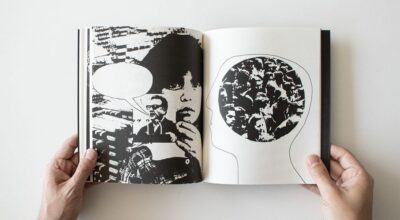

REEDITAN EN ESPAÑOL EL CEREBRO, DE GUILLERMO DEISLER

El libro contiene poemas visuales con reflexiones sobre la sociedad de consumo y el pensamiento crítico, al que el autor agrega un último capítulo donde denuncia los horrores de la dictadura en Chile, cuyos...