Dan Cameron on Curatorial Practice And The Work of Gianfranco Foschino

The distance between becoming a Buddhist monk, a private detective or art curator did not seem to be very large for Dan Cameron (1956, Utica, New York), who began his curatorial practice in the 80s, when it still seemed to be more like a hobby than a profession. He trained with Marcia Tucker, founder of the New Museum, where he had the opportunity to work as Senior Curator between 1995-2006, being responsible for exhibitions of renowned artists, and pioneering in presenting Latin American artists such as Doris Salcedo, Cildo Meireles and Eugenio Dittborn. For him, a curator is like an arbiter of the various processes and discourses that surround artists and art-making, «a kind of triangulation that not everyone is temperamentally suited for.»

For some years now he has worked with Chilean artist Gianfanco Foschino, more recently in his exhibition SED (THIRST), which is on view until January 12 at Matucana 100, in Santiago. It’s amazing, says Cameron, how the agony of thirst can lead you to other sensory forms of consciousness. Although this is not an exhibition focused on water scarcity, nor on the consequences of climate change, it does establish a clear link between the sublime image of the landscape and the terrible state of our current situation. In a room next to SED operates the Centro de Estudios del Agua [Water Studies Center] (CEA), which continually evokes the idea of the individual’s potential agency in the face of climate crisis.

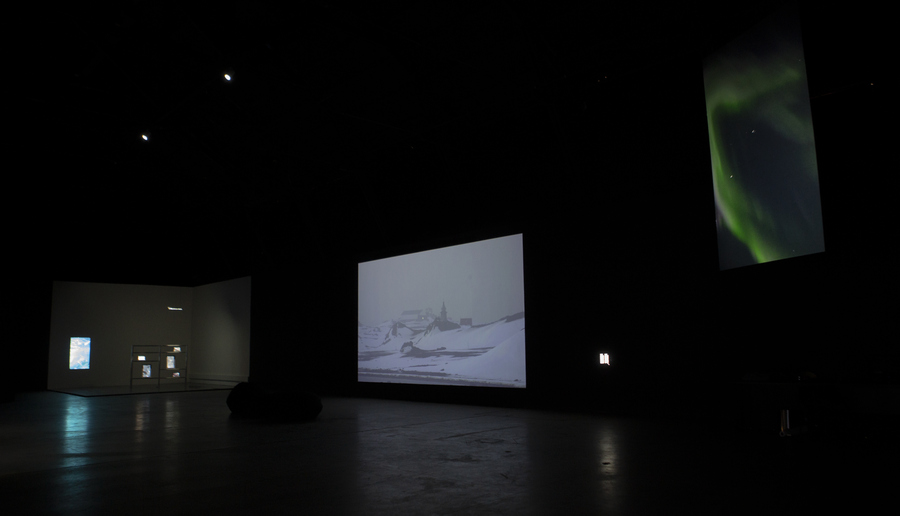

Installation view of the exhibition «Thirst», by Gianfranco Foschino, at the Matucana 100 Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile, 2019. Photo courtesy of the artist

Carolina Castro: Let´s start for the very beginning. How did you become a curator?

Dan Cameron: I don’t remember exactly when I realized that a curator was something one could be, professionally speaking, but I had a keen interest in exhibition-making going back to my teenage years, although it was mixed up with all the other things I wanted to be, like private detective, rock musician and Buddhist monk. By the time I was in university and feverishly reading back issues of art magazines, I had a clearer sense of what the curator’s role was in the bigger picture, and was already making little exhibitions in my spare time (along with other similarly ‘artsy’ activities). I didn’t know about Harald Szeemann’s work back in the late 1970s, but the three most visible curators in my immediate frame of reference were Henry Geldzahler, whose work I wasn’t especially impressed by; Walter Hopps, who everyone agreed was a visionary genius; and Marcia Tucker, who seemed to be fundamentally retooling the concept of what a curator is. I eventually went to work for Marcia, but by then I’d already organized exhibitions in the U.S. and Europe, and also established myself as someone who writes about art.

C.C.: You were lucky to be trained in a pioneer scenario, curatorially speaking, and I have the feeling this influenced your way of curating, so going back to your formative years, what have been the most significant artistic/curatorial milestones for you?

D.C.: Because I’m a curator, getting to see Documenta and Skupltur Projekte Münster for the first time in 1987 fundamentally altered my perception of the international curatorial playing field, and an exhibition that changed my ideas about art and geography — although I never got to see it — was Magiciens de la terre in Paris, in 1989. In the U.S., Mary Jane Jacobs’ 1991 exhibition Places with a Past in Charleston, South Carolina, was a watershed for my generation, as was, on a more global scale, Okwui Enwezor’s 1997 Johannesburg Biennial. For me personally, Rene Block’s 1995 Istanbul Biennial and Paulo Herkenhoff’s 1998 Bienal de Sao Paulo were breathtaking responses to their time and place. More recently, I thought Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s 2012 Documenta was absolutely breathtaking. I should also mention that I see a lot of historical art exhibitions that are somewhat outside my own field, as well as single-artist retrospectives, and these can be incredibly interesting. For instance, the 2018 Hilma af Klint survey at the Guggenheim was a case in point for how certain precepts of art history can be fundamentally changed by a single exhibition.

Having my own first significant museum exhibition be Extended Sensibilities, the first-ever exhibition on gay and lesbian sensibility, at the New Museum in 1982, was very formative because it taught me to operate independently of the dominant ways of thinking about who makes art and for what reasons. In 1986 I was invited by La Caixa in Barcelona and Madrid to organize El Arte y su Doble, which launched me internationally, in the short term my being invited in 1988 to co-organize the Aperto section of the Venice Biennale. Cocido y Crudo at the Reina Sofia in 1994 was definitely a landmark, as were a series of monographic shows I did at the New Museum after Marcia hired me in 1995: Carolee Schneemann, David Wojnarowicz, Martin Wong, Cildo Meireles, Faith Ringgold, Marcel Odenbach, Eugenio Dittbon, Doris Salcedo, William Kentridge, and many others. There were the biennials I did in Istanbul (2003), Taipei (2006), Newport Beach, California (2013) and Cuenca, Ecuador (2016), and of course the launching of Prospect New Orleans, which was my full-time job from 2006 to 2011. I’d also cite as major efforts the Kinesthesia exhibition at Palm Springs Art Museum in 2017, the multi-arts initiative Open Spaces Kansas City in 2018, and the Leandro Erlich retrospective at MALBA in Buenos Aires earlier this year.

C.C.: What kind of things obsess you? I mean … what things in life are important to you, and how have you involved those things in your work.

D.C.: I don’t think of myself as a particularly obsessed person, although I suppose if I were to name a hobby outside of art, it could be politics, even if that interest starts from some pretty basic civic reasons. I’m a person with a high level of curiosity, so I try to provide for myself the latest, most up to date information about whatever is happening artistically wherever I happen to be, and to take part to the extent I’m able. I attempt to see most current gallery and museum exhibitions in New York, for instance, and that in itself is very time-consuming. In general, I start each day expecting to encounter something amazing along the way, and it generally turns out to be true.

C.C.: How do you see curatorship today? What do you think is the role of a curator?

D.C.: I think of the curator as a kind of arbiter of the various processes and discourses that surround artists and art-making. We work directly with artists, but we’re not typically engaged in the marketplace, so our interests can be distanced from the financial transaction. If we work within an institution, then we’re continually balancing the institution’s needs with the artist’s needs, and struggling to fit that juggling act within a coherent experience for the visitor. It’s a kind of triangulation that not everyone is temperamentally suited for. Sometimes a curator is called upon to single out a particular problem to be addressed directly and indirectly through the choices of artists and the development of their projects; while at other times it’s no less direct as making an art historical case for a particular artist’s — or generation’s — significance. The best curators are those who can adapt their vision to multiple exhibition formats: the timeline, the career survey, the genre overview, etc.

C.C.: I’m going to ask you a cliché question. But with all the social changes, the socio-political consciousness we are experiencing now, I think it is valid to ask ourselves again: What is the role of art today?

D.C.: I should say that, first of all, I’m not really a supporter of the notion that our times demand a specific and unique responsiveness from art. I believe art exists first and foremost to expand our shared consciousness as a species, so when the times shift, it’s only natural that what we ask for from art might change accordingly. At moments we want art to probe deep philosophical questions, while at other points we want it to crystallize the most urgent social conditions. But from my experience, artists have their own way of digesting and synthesizing the times they live in, and there have been more occasions than not when a specific artist turns out to have been making work that future generations are in a better position to appreciate than the artist’s contemporaries. On the other hand, those artists who are finding their most ardent form of self-expression in political messaging should never be discouraged from doing so, because we simply don’t know what that art will look like to folks in 50 or 100 years. As a general rule, I just think it works out best when we take artists more seriously overall.

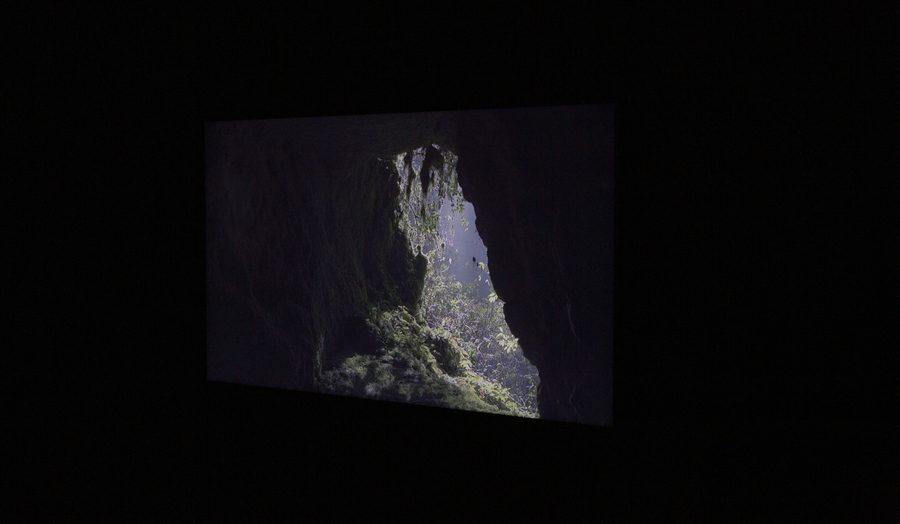

Installation view of the exhibition «Thirst», by Gianfranco Foschino, at the Matucana 100 Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile, 2019. Photo courtesy of the artist

Installation view of the exhibition «Thirst», by Gianfranco Foschino, at the Matucana 100 Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile, 2019. Photo courtesy of the artist

Installation view of the exhibition «Thirst», by Gianfranco Foschino, at the Matucana 100 Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile, 2019. Photo courtesy of the artist

C.C.: I agree with you on that link between art and the expansion of our shared consciousness. I deeply believe in that. And, in that sense, what do you think when I say: water?

D.C.: I immediately think of thirst, because I’ve been in situations, like hiking, when I ran out of water in a place where I really should have put more preparation into my water supply, and there’s a reason you only make that mistake once. Although I never put myself into actual danger, in retrospect I was amazed at how quickly the pangs of thirst can overtake other forms of sensorial awareness, and how much water you can consume if you’ve been deprived of it for a few hours on a strenuous summer hike.

C.C.: SED (Thirst), is the name of the exhibition of Gianfranco Foschino that you are currently curating here, an exhibition linked to water. I know that your work with Chilean artists is long-standing… tell me about your relationship with Chile and SED.

D.C.: I’ve worked curatorially with Eugenio Dittborn and Juan Dávila over the years, and also with Iván Navarro and Sebastián Preece. I first saw Foschino’s video in Venice in 2011, and ended up getting info on him sometime later from Preece, who turned out being a friend of Gianfranco. Then he and I met at SITE Santa Fe in 2014, and from there worked on a couple of projects together, including the Bienal de Cuenca in 2016 and also the Chiloé project. This current show came about largely because during my prior visit to Chile in late 2018, I went to see the Matucana 100 space with Gianfranco just as the dates for the exhibition were being confirmed, so I could later work on the layout from far away.

C.C.: Regarding SED, tell me what the most important works of the exhibition are, and why you included a portrait of the artist in the middle of a selection of works rather linked to nature, landscape…

D.C.: I think there are three works in the exhibition that the rest sort of revolve around thematically. The first is Bellnghausen, which dominates the center of the exhibition space as a kind of visual spectacle of the human impact on pristine areas of Antarctica. The other two are enclosed in separate rooms: Espíritu Santo, which visually situates the viewer in a roadway in the Canary Islands as clouds of fog roll through; and Inside Out, which positions us inside a cave-like space in the Bosque Pehuén (Araucanía), through which we have four different views towards the world outside.

C.C.: How is this exhibition linked to the water crisis we are experiencing today? What is your perspective of the future?

D.C.: I’m not completely sure that an art exhibition is automatically the ideal platform for directly addressing climate change and its impact on the earth’s long-term supply of potable water, but I think this exhibition does succeed in establishing a clear link between the sublime image of the landscape and the dire state of our present situation. It’s almost a right-brain, left-brain response to the same situation, in that even though the exhibition SED is aesthetically concerned with emphasizing sharp contrasts in scale between so-called personal space and landscape, the Centro de Studios de Agua, which operates next door as a sort of learning annex, continually evokes the idea of the individual’s potential agency in the face of climate crisis.

Water Studies Center (CEA), at the Matucana 100 Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile, 2019. Courtesy: CEA

Water Studies Center (CEA), at the Matucana 100 Cultural Center, Santiago, Chile, 2019. Courtesy: CEA

También te puede interesar

Bordes de la Cotidianidad.videos de Artistas Colombianos

El Parqueadero, el laboratorio de proyectos artísticos del Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia del Banco de la República – MAMU, en Bogotá, exhibe por estos días "Bordes de la cotidianidad", un proyecto curatorial de...

TROIKA Y LA SAL COMO PROTAGONISTA DE LA DOMINACIÓN MUNDIAL

¿Qué pasa si, desde hace milenios, la sal ha interrumpido y moldeado deliberadamente la agencia humana al permitir el avance tecnológico, desde la fabricación de la primera herramienta de pedernal hasta la invención del...

BRAIN FOREST QUIPU. CECILIA VICUÑA EN LA TATE MODERN

Dos grandes quipus tejidos que cuelgan a 27 metros de altura, audios con cantos tradicionales y músicas contemporáneas, videos protagonizados por comunidades indígenas y un ciclo de encuentros de activistas por el cambio climático,...