Prem Sarjo:walking Around

Los alquimistas medievales seguían una vieja doctrina según la cual la búsqueda de objetos preciosos se ha de hacer entre la basura. No ha de extrañarnos que éste antiguo descubrimiento se haya perpetuado en las ideas del arte, siguiendo un curso de sutiles diferencias hasta nuestra contemporaneidad. La idea de hallazgo sagrado permanece, lo que cambia es el concepto de ese descubrimiento. Es ahí donde reside la idiosincrasia de una sociedad determinada.

Cada fotografía de Sarjo es el hallazgo no manipulado de una escena citadina y diurna. Lo que sucede en ella es una interrogante, pues más bien tenemos la huella de lo ocurrido, que es capturada por el ojo de la cámara. Entonces se produce algo nuevo, nacido en ese instante. Los carteles publicitarios tienen dos espacios: uno informativo y el otro en donde descansa el vacío. La vida urbana también tiene dos caras: una que está pensada en nosotros para que la consumamos, otra que permanece oculta, pues podemos tenerla en frente pero -curiosamente- no la vemos. Del mismo modo, las relaciones humanas se desarrollan en la directriz que se muestra y que está emparentada con lo moralmente correcto, y en otra que se mantiene sepultada, lejos de las miradas, y que la mayoría de las veces ni nosotros mismos notamos.

La calle es el espacio en donde la vida social se desenvuelve. Bajo nuestros pies están las entrañas de esa calle, aunque nunca pensemos en ellas. Ahí se esconden los productos de nuestra existencia que hemos preferido desechar conscientemente, pues nos producen malestar. Es extraño que esa sea la forma en la que hemos preferido asumir nuestra vida en sociedad, puesto que al parecer las marcas de existencia que tanto nos esmeramos en ocultar aparecen insistentes, como si no hubiera espacio suficiente para ellas en las profundidades de la tierra.

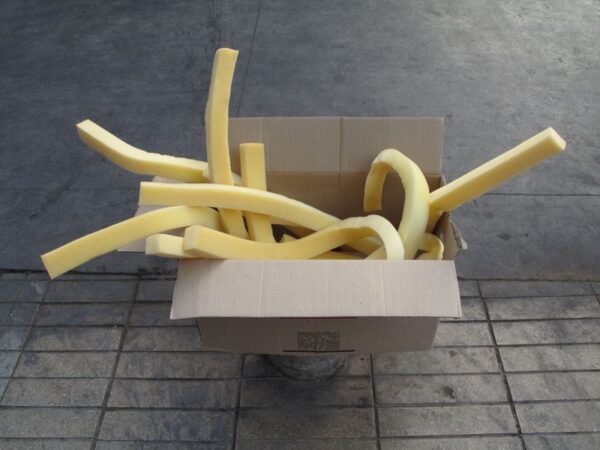

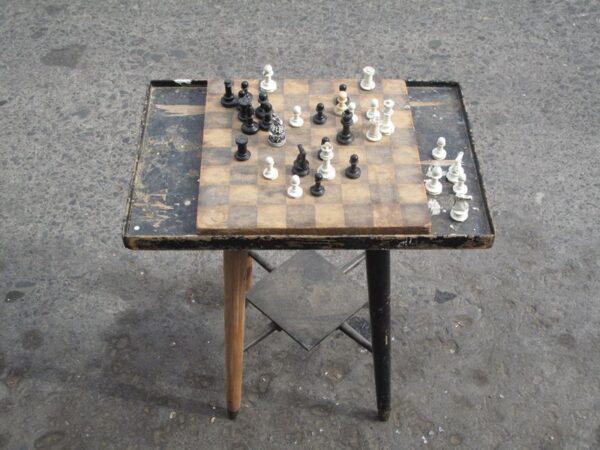

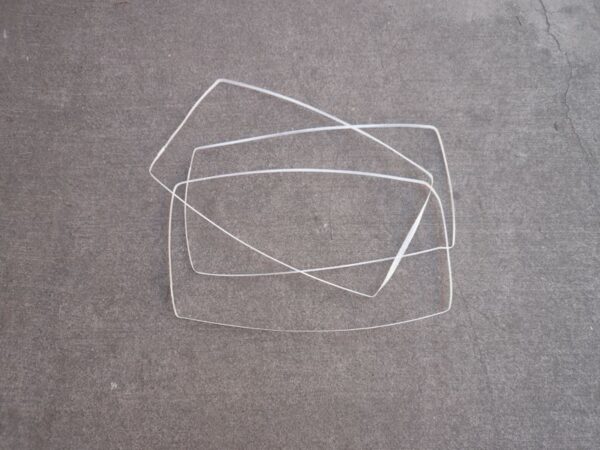

La razón por la que existen objetos valiosos y otros dignos de ser llamados «basura», es porque nos recuerdan a nuestro propio miedo a la muerte, y eso nos paraliza de terror y asco. Sin embargo, todo lo que nos rodea -incluyéndonos- está destinado a morir. Observar en éstas fotos lo que sucede con los cadáveres de las creaciones humanas es de lo más sorprendente. Aparece un orden oculto, mezcla de casualidad e intervención consciente: un molde para hormigón es el coliseo romano desafiando a las estructuras de la naturaleza para levantarse con la sola ayuda de la mano del hombre, un colchón abandonado en un carro de basura se convierte en un dinosaurio devorador, dos sillas de plástico apiladas descubren su secreta acción amorosa, la caja de cartón desarmada y puesta con piedras en el suelo para delimitar un territorio es la cara de un robot que sonríe. Todos los hallazgos nos los señala el ojo que juega de la mano con la imaginación de un niño, pero también con un hombre que reflexiona sobre su oficio, y se ocupa de citar a la historia del arte. Así, en un simple paseo por la calle podemos encontrarnos a Mondrian en un refrigerador mutilado y apoyado ordenadamente en un basurero, estructuras minimalistas que hacen brillar su presencia desnuda desde la espalda de un camión, citas a la pintura en las esquinas de naturalezas muertas, o la ventana a una marina en el color de una pared descuidada donde un bote rojo tuvo en otra vida el papel de alfombra. Y no es menor el hecho de encontrar poesía en las espaldas de las cosas creadas por el ser humano. Es la cara que no está concebida para que veamos, es la parte de nuestra personalidad que no expresamos en nuestras relaciones sociales, es el misterio de lo que no declaramos al vivir. La cámara puede separar las cosas invisibles del mundo.

Los nombres de las fotografías guían al observador a una nueva lectura. La mayoría apuntan a un sentido del humor fresco e inocente. Sin embargo, hay una crudeza que no se puede dejar de lado, y se refiere a la realidad social en que han aparecido los registros de acciones que ya no se ven. La manera en la que se ordena y recolecta habla de una forma de pensar que va mucho más lejos de nuestros procesos conscientes. Una barrera improvisada de obrero en Santiago, jamás será la misma que la de un obrero en cualquier otra parte del mundo. Esas maneras de transformar el espacio adquieren un carácter que problematiza a las manifestaciones artísticas contemporáneas, e inevitablemente surge la idea de que un hallazgo callejero podría estar en la sala de un museo y ser una pieza de arte. En Walking Around aparecen situaciones visuales que evalúan directamente a «lo chileno», como las soluciones «parche» que se toman para no arreglar de fondo el problema por pereza. Esas alternativas literalmente mal hechas suelen acumularse, y entonces el problema que en un comienzo era mínimo, se hace irreparable. Otra constante de la conducta chilena que Sarjo rescata con ironía son los sistemas de seguridad. La construcción de ellos, muchas veces, es absurda, y responde a la misma idea de la falsa solución parche. Esas construcciones se elaboran a veces con saña, y entonces surgen verdaderas prisiones que hieren la vista, ofenden, y dan una idea muy elaborada de lo que puede significar el miedo en algunas familias.

Dentro del espacio sórdido a donde nos puede llevar la lectura más profunda que podamos edificar, se encontrará otro lugar más delicado: la poesía. ¿Cómo encontrar belleza y armonía en una opinión sobre las cosas que apunta a la degradación y a la muerte? Las respuestas pueden ser tan variadas como las otras preguntas que puedan surgir a raíz de ellas. Este es el punto más evanescente de las imágenes, por lo que no es cosa fácil atraparlo. El poema de las fotografías de Walking Around es muy sutil, porque reflexiona en tono místico sobre la idea de la muerte, y lo hace a partir de materiales que no son nobles. Podría parecernos conflictiva la situación en la que se encuentra el poema, pero es justamente lo contrario, pues se ancla siempre en la realidad. Jamás se despega de ella. Por eso la belleza que aparece chispeante en la fotografías es ineludible: es el hallazgo de la elegancia dentro de la corrupción de los cuerpos, metamorfoseados en extrañas mariposas. Las cosas muertas tienen las voces de los seres que ya no las ven. Por eso nunca aparece el hombre en las fotos, sin embargo, es siempre el protagonista, y dice: «somos más libres de lo que pensamos.»

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

PREM SARJO: WALKING AROUND

BY ROCÍO CASAS BULNES / TRANSLATION BY SEBASTIÁN JATZ RAWICZ

The alchemists from the Middle Ages pursued an ancient doctrine according to which precious materials could be derived out of waste. It shouldn’t be a surprise then that this old discovery has been perpetuated since in the realm of the arts, following a course of subtle variations up to our times. The notion of a sacred found object is still with us, what has changed is the concept of this finding. This is where the idiosyncrasy of a particular society resides.

Every photograph by Sarjo is a non-manipulated finding of an urban scene in broad daylight. A question is what springs from it, for we only posses a trace of what had happened, captured by the lens of the camera. So something new is produced, born in that instant. Publicity signs have two different spaces: one which informs us and one where lies a void. Urban life has two different sides as well: one whose intention is for us to consume and another which lies hidden, for we may have it right in front of us, but oddly enough, we don’t see it. Similarly, human relationships develop according to these guidelines, which is related to what is morally correct but there is another one that remains buried, far from people’s gaze and which, most of the time, we ourselves don’t even notice.

The street is the space where social life flourishes. It’s guts lie beneath our feet though we may never stop to think about it. Down there lie those products of our existence which we have consciously chosen to throw away, for they make us uneasy. It is strange that we have chosen this method to assume our lives within society, for it seems that these scars of our existence, which we try so hard to get rid of, keep showing up, as if there was no room left for them in the depths of the earth.

The reason why we have valuable objects and others which are deemed as “waste” is because they remind us of our own fear of death, and that paralyses us with fear and repugnance. Nonetheless, all that surrounds us – including ourselves – is destined to die. It is remarkable to see what happens in these photographs with the corpses of human creation. There is a hidden logic, between chance and conscious intervention: a cast for concrete turns into the Roman Coliseum defying nature’s shapes, rising with the sole help of man’s hand, an abandoned mattress by a garbage truck becomes a devouring dinosaur, two piled up plastic chairs discover their secret loving passion, the teared carton box lying on the ground with a stone on it to delimit someone’s territory changes into the face of a smiling robot. All the findings are displayed by the eye that plays hand in hand with a child’s imagination, but also the man that reflects on his trade, who is concerned with referring to art’s history. Thus, on an ordinary street walk one could find Mondrian in a mutilated refrigerator carefully leaning against a trash can, minimalist structures that glow in their naked presence from the back of a truck, quotes on still life on the paint in corners, or a glance into a seascape amongst the colors of a worn out wall where a red boat previously had the role of a carpet. It is quite significant to be able to find the poetry behind these things created by the human being. It is that side that was not conceived so as to be seen, it is that part of our personality which we choose to conceal in our relationships, it is the mystery of that we do not declare while we live. The camera may split the invisible things of this world.

The names given to these pictures guide the observer towards a new interpretation. Most of them are directed towards a fresh and innocent sense of humor. However, there is a harshness which cannot be ignored, and which refers to the social reality of the recordings of these actions which are no longer visible. The way in which it is ordered and recollected relates to a way of thinking that goes beyond our conscious processes. A makeshift workman’s barrier in Santiago will never be the same as another one in any other part of the world. This space-transforming procedure acquires a characteristic that presents a problem to contemporary artistic methods and, inevitably surfaces the notion that a street finding may as well be inside a museum and thus be considered a work of art. In Walking Around visual situations emerge which directly evaluate what is “typically Chilean”, such as “patch” solutions, which are made out of laziness, never solving the core issue at hand. These alternatives, which are literally poorly made, tend to add up, so a problem which was once a small thing suddenly becomes unfixable. Another constant in Chilean behavior that Sarjo recovers ironically are the security systems. Quite often their construction is plainly absurd, thus belonging to the same false notion of “patch” solutions. These constructions are sometimes carried out with viciousness and then effective prisons which hurt our eyes are created, giving us a very elaborated insight into what fear can represent for certain families.

Within the sordid space that a more profound reading can give us we will find a more delicate possibility: poetry. How can we find beauty and harmony in things that aim towards degradation and death? The answers may be as diverse as the other questions that may be born out of them. This is the most evanescing point of these images, that is why it is easy to get hold of it. The poetry in the photographs that make Walking Around is a very subtle one, because they reflect the notions of life and death with a mystical tone out of those base materials. We may think that this poem is in a situation of conflict but it is actually quite the opposite, for it is always rooted in reality. It never departs from it. That is why we can’t escape the sparkling beauty of these photographs: it is finding the elegance within the corrupting bodies, morphed into strange butterflies. Dead things carry the voices of those beings which no longer can see them. That is why there is never a person in these photographs, however, people will always be its protagonist, by saying: “we are freer than what we think.”

También te puede interesar

FALSOS TERRENOS EN PEQUEÑAS DIMENSIONES: RODRIGO LOBOS EN DIE ECKE

El tópico de la memoria es hoy en día una constante en el arte contemporáneo. Muchos artistas trabajan a partir de sus memorias, personales o colectivas. Pretenden hacer del pasado un objeto que pueda…

PALOMA VILLALOBOS: “ARCHIVO NATURAL ANTÁRTICO DESARTICULA LA IDEA DE AUTORÍA EN LA FOTOGRAFÍA”

El ala norte del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes alberga hasta el 15 de septiembre la obra Archivo Natural Antártico de la fotógrafa Paloma Villalobos (Chile, 1976), quien junto a los artistas Gabriel del…

EL CUARTO OSCURO. SOBRE “LA BROMA ASESINA” DE JAVIER RODRÍGUEZ

"La broma asesina" es el título de un relato gráfico que monta el artista chileno Javier Rodríguez en colaboración con la curadora Soledad García en el marco de la exposición colectiva "Lunes es revolución"....