Polvo, Ceniza y Arte

[Please scroll down for English version]

En la película Melancolía (2011), de Lars von Trier, los personajes principales se enfrentan a la inminente colisión de un planeta llamado Melancolía con la Tierra, lo que podría significar el fin del mundo. En el libro Acontecimiento (2014), Slavoj Žižek analiza esta película a través de la idea del ‘Acontecimiento’ como algo que “surge aparentemente de la nada”[1] e irrumpe la realidad, desestabilizando las estructuras que la sostienen. A partir de esta premisa, Žižek plantea el posible choque del planeta como el acontecimiento de la película y analiza cómo cada uno de los personajes lo vive por medio del marco a través del cual entienden su entorno.[2] El arribo de un acontecimiento inevitablemente causa una alteración en nuestra manera, no sólo de entender la realidad, sino de relacionarnos con ella.

En el caso del contexto del arte contemporáneo en México, el acontecimiento del momento no es la colisión de un “planeta azul telúrico”[3] contra la Tierra, sino una obra de arte de Jill Magid (EEUU, 1973): The Proposal [La propuesta] (2014-16), un anillo con un diamante azul de 2.02 quilates, creado usando 525 gramos de las cenizas del arquitecto Luis Barragán (México, 1902-1988).

Jill Magid, The Proposal (La propuesta), 2016,, diamante azul sin cortar de 2,02 quilates con la inscripción en micro-láser «Soy sinceramente suyo», anillo de plata, caja de anillo, documentos. Diseño de montaje: Anndra Neen. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich y Galerie Untilthen, París. Foto: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen / Stefan Jaeggi

Jill Magid, Vitrina del Artista (Informe Gemológico a la izquierda y Certificado de Diamante a la derecha) (detalle), 2016. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich y Galerie Untilthen, París. Foto: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen / Stefan Jaeggi

The Proposal forma parte de un extenso proyecto multimedia de Jill Magid, The Barragán Archives [Los archivos Barragán] que comienza en 2013 y a través del cual la artista investigó el manejo del acervo, dividido en dos partes, del célebre arquitecto, único mexicano en haber recibido el Premio Pritzker, para ahondar en el control que se ha llegado a ejercer sobre este legado. El archivo personal de Luis Barragán y su biblioteca son manejados por la Fundación de Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán A.C. (FATLB) en conjunto con el Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco, y se encuentra en Casa Luis Barragán en la Ciudad de México, otrora casa y estudio del arquitecto que en 1994 fue establecida como un museo. Mientras que el archivo profesional, manejado por The Barragan Foundation –establecida en 1996 con el apoyo de Vitra, corporación suiza fabricante de muebles– se encuentra en el campus de Vitra, en Birsfelden, cerca de Basilea. Este archivo fue adquirido en 1995 por el dueño de Vitra, Rolf Fehlbaum, y supuestamente fue un regalo de compromiso para su actual esposa y directora de The Barragan Foundation, la italiana Federica Zanco. A través del acervo de Barragán, Magid cuestiona los organismos de poder que regulan el acceso a estos archivos al igual que la complejidad de los derechos de autor en nuestra actualidad y cómo todo esto puede llegar a determinar el legado entero de un artista.

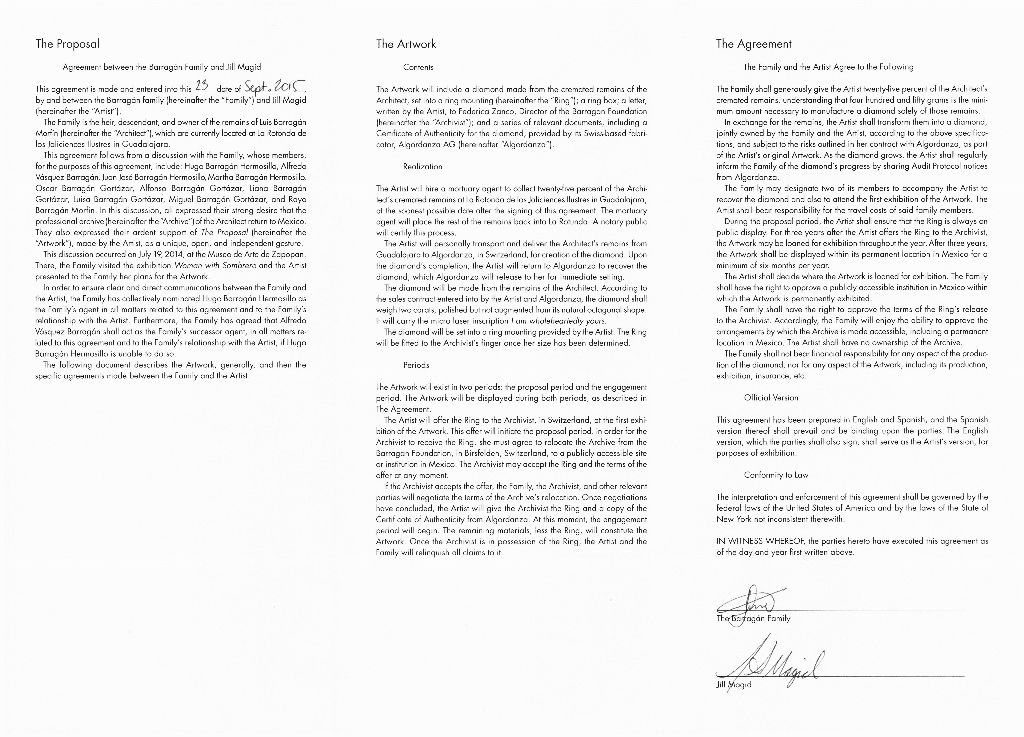

The Barragán Archives ha conllevado un arduo proceso de casi cuatro años de investigación por parte de Magid. Esta investigación se ha manifestado en la creación de diversas obras y exposiciones.[4] No obstante, el proyecto llega a un momento crucial precisamente con la pieza The Proposal –y la exposición que lleva el mismo nombre [5]–, ya que la obra no sólo engloba el anillo, sino una atrevida propuesta: el ofrecimiento de éste por parte de Magid a Federica Zanco, a cambio de abrir el archivo profesional de Barragán al público en México.[6] “El cuerpo por el cuerpo de trabajo”.[7]

Vista de la exposición de Jill Magid, The Proposal, 2016, San Francisco Art Institute. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich; Galerie Untilthen, París. Foto: Gregory Goode

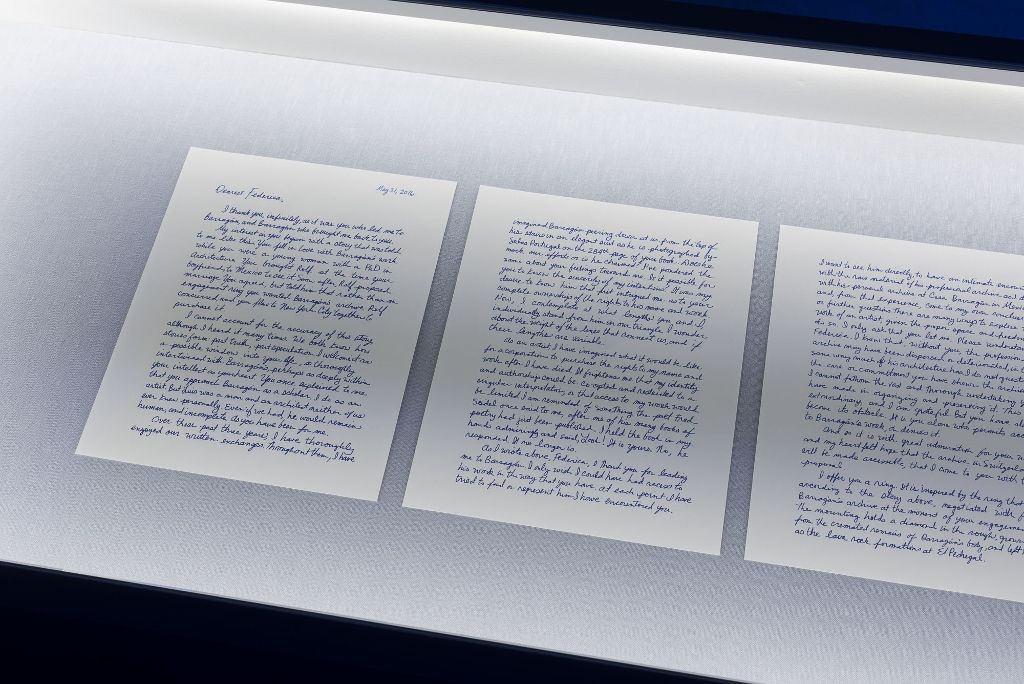

Jill Magid, La Vitrina del Arquivista (detalle), 2016, vitrina, facsímil de la carta de Propuesta a Federica Zanco, 4 páginas. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich; y Galerie Untilthen, París. Foto: Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen / Stefan Jaeggi

El primero de agosto de este año –una semana después de la inauguración de Ex-Voto en la galería mexicana LABOR [8]–, se publicó el artículo The Architect Who Became a Diamond [El arquitecto que se convirtió en diamante], de Alice Gregory en The New Yorker.[9] Esta cautivadora narración que detalla el proyecto de Magid detonó una serie de artículos polémicos alrededor de The Barragán Archives, escritos por una diversidad de personalidades de distintos ámbitos, inclusive algunos ajenos al mundo del arte: una docena de importantes plumas, como las del escritor y periodista Juan Villoro,[10] el también escritor y analista político Jesús Silva-Herzog Márquez [11] y los curadores y críticos Daniel Garza-Usabiaga [12] y Cuauhtémoc Medina.[13]

Estos artículos ponen en evidencia las construcciones sociales que rigen los sistemas que habitan estos autores –ahora soy una más– y reflejan las distintas maneras en que enmarcamos la realidad. Algunos, como yo, nos aproximamos a la obra con asombro, mientras que otros lo hicieron con disgusto o inclusive con horror.

Tal como sucede en Melancolía, aquí se presenta un acontecimiento: The Proposal como parte del proyecto de arte The Barragán Archives. Cada uno nos enfrentamos a este acontecimiento desde los distintos lentes de nuestras propias historias y fantasías, las cuales determinan nuestra construcción de la vida. ¿Se trata de la fantasía de la imagen de Barragán? ¿Del contenido del archivo? ¿Del arte mismo? O bien, ¿la fantasía de dos mujeres: Jill Magid y Federica Zanco?

Una de las posturas de la crítica se enfoca en la pieza The Proposal y plantea una problemática de forma. Aquí podemos ubicar los textos de Juan Villoro y de Jesús Silva-Herzog Márquez, quienes refutan el proceso que condujo a la creación de este anillo y lo conciben como una especie de profanación al lugar de descanso del arquitecto y a su propio patrimonio. Si el origen de esta postura fuera de índole religiosa –aunque ninguno de los dos autores lo expresó así–, no habría nada que decir, ya que por definición la fe no se puede refutar.

En una inquietud por explorar otra manera de ver y comprender la exhumación de las cenizas de Barragán, visité la exposición The Proposal en el San Francisco Art Institute. Conversé con Hesse McGraw, vicepresidente de exposiciones y del programa público y curador de la muestra –que estará expuesta en las Galerías Walter y McBean hasta el 10 de diciembre–, quien expresó cómo la obra no sólo exhumó los restos de Barragán, sino también abrió nuevas posibilidades para su legado.

McGraw habló del doble significado de la palabra “exhumar”: el primero efectivamente tiene que ver con desenterrar restos humanos, pero la segunda definición es “sacar a la luz lo olvidado”.[14] Al decir de McGraw, “la idea de que este proyecto esté trayendo al archivo y al legado nuevamente como temas de conversación, de maneras en que no se había hecho antes, es algo muy poderoso”.[15] Él ve The Proposal a través de un marco de creación artística, sin connotaciones religiosas. Exhumar las cenizas de Barragán para tomar 525 gramos y tornarlas en una obra de arte, constituye una especie de alquimia poética y política.

Dentro de las reacciones negativas ante The Proposal, también hay críticas que trascienden la exhumación y se enfocan en las cualidades simbólicas comúnmente atribuidas a los diamantes. El argumento se centra alrededor de la idea de que un diamante representa ostentación y glamour, atributos ajenos a los ideales de Barragán. Juan Villoro dice: “El maestro de los espacios austeros es ahora un adorno banal. ¿Qué explica este grotesco reciclaje?” [16]. Quizás esto puede ser explicado a través de la historia del arte mismo: el simbolismo de un objeto cambia al ser insertado en el sistema del arte.

Tan solo pensemos en La fuente (1917) de Marcel Duchamp. Efectivamente en ese entonces –hace casi un siglo–, la obra de Duchamp fue recibida con gran polémica, los críticos etiquetaban los ready-mades como inmorales y vulgares e incluso los consideraron un plagio [17]. Sin embargo, aquel mingitorio acabó por convertirse en fuente y Duchamp cambió el curso de la historia del arte y abrió el camino para el arte conceptual. Quizá también es un buen momento para releer las reflexiones de Octavio Paz sobre esto en Marcel Duchamp o El castillo de la pureza (1968) y en Apariencia desnuda (1973).

Como el urinario de Duchamp pasa a ser una fuente, de la misma manera el anillo de Magid ya no puede ser visto como una joya. En mi opinión, el diamante brilla pero no con una luminosidad arrogante y fatua, sino con un resplandor que nos muestra las penumbras de nuestro tiempo. Antes de viajar a San Francisco, la exposición The Proposal estuvo en St. Gallen, Suiza, en el Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen. En ninguna de estas dos ciudades se suscitó el revuelo que hubo en México. Podría argumentarse que fue porque el arquitecto convertido en diamante no era estadounidense ni suizo, que a lo mejor la reacción hubiera sido distinta si estuviéramos hablando de las cenizas de Frank Lloyd Wright o Le Corbusier.

¿O será más bien que esto tiene que ver con el peso de nuestro bagaje histórico que aún limita nuestra manera de entender ciertas cosas? The Barragán Archives presenta una forma de arte cuya práctica evidentemente no apela a los anhelos formales de muchos en México. Sólo hay que recorrer la historia del arte y ver la transformación del mismo, que no es más que un reflejo de la evolución del propio ser humano.

¿Será coincidencia que hace solamente algunas semanas el Vaticano prohibiera públicamente que las cenizas de los difuntos sean convertidas en piezas de joyería o esparcidas en la naturaleza? ¿O es posible que una “mera” obra de arte tenga el poder de infiltrar las gruesas paredes de la sede católica? Hay que recordar que una característica de la práctica artística de la propia Magid ha sido subvertir el orden establecido mediante el resquebrajamiento de algunos de los sistemas de autoridad más notorios como el cuerpo policiaco de Nueva York, el servicio secreto holandés y otros regímenes de vigilancia. ¿El poder del arte?.

Jill Magid, The Exhumation (La Exhumación), video, 2016. Comisionado por Field of Vision como parte de un proyecto más grande en colaboración con la artista. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich; y Galerie Untilthen, París. Foto: Jarred Alterman

Jill Magid, The Exhumation (La Exhumación), video, 2016. Comisionado por Field of Vision como parte de un proyecto más grande en colaboración con la artista. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich; y Galerie Untilthen, París. Foto: Jarred Alterman

Regresando al alegado valor mercantil de The Proposal, en el artículo Las cenizas del arquitecto, Silva-Herzog Márquez expresa: “Un mundo que mercantiliza todo es un mundo que hace pose artística con todo […] Todo es mercancía para el discurso del arte conceptual, tan escaso de arte, tan pobre en concepto y tan abundante en rollo” [17]. Basta con indagar un poco en el proyecto de Magid para percatarse de que el anillo es todo menos mercancía; es poesía.

Existe un contrato legal que estipula que la pieza jamás puede ser vendida, por ende su importancia no es monetaria. Es un regalo que sólo puede recibir Federica Zanco. The Proposal ya no debe verse como una alhaja, sino como una obra de arte cuyo valor va más allá de lo económico. Porque un anillo también simboliza un compromiso, en este caso un compromiso con el arte.

Al parecer, The Proposal se ha convertido en un elemento amenazador, como el planeta que chocará contra la Tierra en Melancolía. ¿Un reflejo de un miedo a una “otredad” en la que un objeto no puede ser concebido más allá de su forma? ¿Pero qué pasa si esa forma que violenta a tantos era necesaria para causar el efecto que se desencadenó? Y más allá de esto, ¿qué sucede si consideramos la selección de un anillo de compromiso como una decisión deliberada por parte de la artista?

Lejos de ser un gesto “ingenuo” yo veo la determinación de Magid de convertir las cenizas de Barragán en un diamante –algo efectivamente inadecuado para representar al arquitecto– y no en un objeto afín a él, como un acto consciente. Ella domina la doble significación del anillo: superfluo e imprescindible, ilusorio e innegable, lúgubre y prometedor. Magid sabía que sólo un símbolo tan lejano a Barragán sería capaz de dislocarnos, precisamente a través de la ironía de este, la cual inevitablemente nos obliga a mirar desde otro lugar.

En la película Melancolía, cuando los personajes observan cómo este planeta se aproxima a la Tierra, para tranquilizar a Claire, John le dice que lo mire a través de un círculo de alambre y que lo vuelva a ver diez minutos después para comprobar que la forma se ha vuelto más pequeña, una prueba de que Melancolía se está alejando de la tierra.[18] Si nos asomáramos por ese círculo de alambre y lo apuntáramos al anillo, veríamos que a raíz de la polémica el diamante ha crecido de manera exponencial.

Jill Magid, Cena Familiar, Museo de Arte de Zapopan, Guadalajara, México, 19 de julio de 2014. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich; y Galerie Untilthen, París

Jill Magid, El Acuerdo Familiar, 2016. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich; y Galerie Untilthen, París

Es gracias a The Proposal que llegamos a los archivos de Luis Barragán, la herencia de un artista a su mundo, a su siglo, y al núcleo del proyecto de Magid, quien se pregunta respecto al legado de un artista, “cómo es construido, manipulado, consultado y poseído”.[20] O quizás otra pregunta sería, ¿qué responsabilidades debe tener una institución que se adueña de un legado, no sólo con el artista, sino también con el público?

La propuesta de Magid no sólo va dirigida a Federica Zanco para que literalmente abra el acervo, sino a cada uno de nosotros para que cuestionemos nuestra manera de relacionamos con las estructuras de poder, y hasta con las posibilidades y los límites del arte. Es probable que Magid esté consciente de que su propia práctica no puede escapar lo comercial, ya que aunque The Proposal no puede ser vendida su práctica se mercantiliza a través de las galerías que la representan. Por esto, tampoco me parecería descabellado que a través de The Barragán Archives Magid se cuestione su papel en el sistema y reconozca su propia complicidad dentro de este.[21]

The Proposal no sólo interrumpe, sino que irrumpe. Crea rupturas en un sistema ya fracturado que inevitablemente nos confronta con nuestras propias fallas, carencias y maneras estrechas de enmarcar lo que nos rodea. Nos enfrenta con lo que Žižek cataloga como lo “conocido desconocido”: “…las creencias y las suposiciones negadas de las que ni siquiera somos conscientes y que se adhieren a nosotros”.[22] Así, el anillo se convierte en un Acontecimiento, en “la exposición de la realidad que nadie quiere admitir, pero que ahora se ha convertido en una revelación, y que ha cambiado las reglas del juego”.[23] La controversia surgida es ahora parte de la obra. Cada uno de estos artículos se vuelve una estrella en la constelación de The Barragán Archives.

Hay algo vital que se escapa a todo esto. En su discurso al recibir el Premio Pritzker en 1980, Barragán dijo: “Es alarmante que las publicaciones dedicadas a la arquitectura hayan desaparecido de sus páginas las palabras Belleza, Inspiración, Magia, Hechizo, Encantamiento…”[24] ¿Acaso el polémico anillo no tiene un toque de cada una de estas palabras tan valoradas por el propio arquitecto? Después de todo, como dice Jill Magid, “…la herramienta más radical del pragmatismo es la poesía”.[25]

[1] Slavoj Žižek, Acontecimiento, trad. Raquel Vicedo, Madrid, Editorial Sexto Piso, 2014, p. 16.

[2] Ibid., pp. 28-35.

[3] Ibid., p. 29.

[4] Cronología de exposiciones: The Proposal [La propuesta], San Francisco Art Institute: Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco, 2016; Ex-Voto, LABOR, Ciudad de México, 2016; The Proposal, Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gallen, 2016; Woman with Sombrero [Mujer con sombrero], Museo de Arte Zapopan, Guadalajara, 2014; Quartet [Cuarteto], South London Gallery, Londres, 2014; Homage [Homenaje], RaebervonStenglin, Zúrich, 2014; Woman with Sombrero, Yvon Lambert, París, 2014; Woman with Sombrero, Art in General, Nueva York, 2013; Der Trog [El bebedero], Art Basel Parcours, 2013.

[5] The Proposal fue un encargo del San Francisco Art Institute. La exposición está curada por Hesse McGraw, vicepresidente de exposiciones y del programa público del SFAI, y organizada con Katie Hood Morgan, asistente curatorial y gestora de exposiciones.

[6] Cita textual de la carta de Propuesta a Federica Zanco: “The ring will always be available to you, and to you alone, whenever you are ready to open the archive to the public in Mexico.”

[7] Jill Magid, comunicado de prensa de The Proposal, San Francisco Art Institute.

[8] En LABOR –la galería que representa a Magid en México y se encuentra frente a Casa Luis Barragán–, Magid mostró Ex-Voto (del 23 de julio al 3 de septiembre de 2016). En esta exposición no se mostró la pieza The Proposal, sino “dos nuevas esculturas, su trabajo de video The Exhumation [La exhumación], y una serie de ex-votos. Un Ex-Voto, a menudo se hace como una pintura narrativa sobre una placa de estaño o aluminio, estos son presentados a un santo o divinidad en cumplimiento de un voto. En la exhumación de las cenizas de Barragán en la Rotonda de los Jaliscienses Ilustres, Magid hizo a Barragán una ofrenda votiva: un caballo de plata, equivalente a los 525 gramos de sus cenizas que se retiraron de la urna, y que fue colocado permanentemente de nuevo en ella. Los Ex-Votos de Magid, son una serie de cuatro caballos de aluminio pintado, agradeciendo a la familia Barragán, al Gobierno de Jalisco, al caballo de plata y al diamante, hecho únicamente a partir de los restos de Barragán. Un quinto caballo será producido cuando y si el anillo es aceptado” (Extracto del comunicado de la exposición, disponible en http://www.labor.org.mx/jilll-magid-ex-voto/).

[9] Alice Gregory, “The Architect Who Became a Diamond” [El arquitecto que se convirtió en dimanante], The New Yorker, 1 de agosto de 2016. Disponible en: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/08/01/how-luis-barragan-became-a-diamond

[10] Juan Villoro, “Anillo de Compromiso”, Reforma, 5 de agosto de 2016 y “De vuelta a las cenizas”, Reforma, 12 de agosto de 2016.

[11] Jesús Silva-Herzog Márquez, “Las cenizas del arquitecto”, Andar y ver: el blog de Jesús Silva-Herzog Márquez, 11 de agosto de 2016. Disponible en: http://www.andaryver.mx/

[12] Pamela Ballesteros entrevista a Daniel Garza-Usabiaga, Entrevista | Daniel Garza-Usabiaga, La implicación del archivo Barragán, GASTV, agosto de 2016. Disponible en:

Parte uno: http://gastv.mx/entrevista-daniel-garza-usabiaga-la-implicacion-del-archivo-barragan/

Parte dos: http://gastv.mx/entrevista-daniel-garza-usabiaga-la-implicacion-del-archivo-barragan-parte-ii/

[13] Cuauhtémoc Medina, “Un anillo embrujado”, Excélsior, 19 de agosto de 2016. Disponible en: http://www.excelsior.com.mx/opinion/columnista-invitado-comunidad/2016/08/19/1111937

[14] Real Academia Española. Exhumar, en Diccionario de la lengua española (23.a ed.), 2014. Recuperado de: http://dle.rae.es/?id=HFF3tzp

[15] Hesse McGraw, conversación personal, noviembre de 2016.

[16] Villoro, op. cit., “Anillo de compromiso”.

[17] MoMA Learning, “Marcel Duchamp and the Readymade” [Marcel Duchamp y el ready-made]. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/dada/marcel-duchamp-and-the-readymade

[18] Silva-Herzog Márquez, op. cit.

[19] Žižek, Acontecimiento, op. cit., p. 30.

[20] Jill Magid, “Locating Legacy: Jill Magid in Conversation with Nikolaus Hirsch and Hesse McGraw” [Localizando el legado: Jill Magid en conversación con Nikolaus Hirsch and Hesse McGraw], en Nikolaus Hirsch, Carin Kuoni, Hesse McGraw y Markus Miessen (eds.), The Proposal. Jill Magid (Critical Spatial Practice 8), Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2016, p. 6.

[21] Lo anterior me recuerda las palabras de la artista Andrea Fraser, “…la institución está dentro de nosotros, y nosotros no podemos salir de nosotros mismos.” En De la crítica institucional a la institución de la crítica, Siglo XXI Editores, 2016, p. 22.

[22] Žižek, op. cit., p. 23.

[23] Ibid., pp. 25-26.

[24] Luis Barragán, “Ceremony Acceptance Speech” [Discurso de aceptación de ceremonia], The Hyatt Foundation / The Pritzker Architecture Prize, 1980. Disponible en: http://www.pritzkerprize.com/1980/ceremony_speech1

[25] Magid, “Locating Legacy…”, en Hirsch, Kuoni, McGraw y Miessen (eds.), op. cit., p. 15.

Jill Magid, still de video en proceso, 2016. Comisionado por Field of Vision como parte de un proyecto más grande en colaboración con la artista. Cortesía de la artista; LABOR, Ciudad de México; RaebervonStenglin, Zurich; y Galerie Untilthen, París. Foto: Jarred Alterman

DUST, ASHES AND ART

By Othiana Roffiel

Translated by Christopher Fraga

In Lars von Trier’s film Melancholia (2011), the main characters are faced with the imminent collision of a planet called Melancholia with Earth, which might spell the end of the world. Slavoj Žižek analyzes this film in his recent book Event (2014), through the titular concept of the «event» as «something that emerges seemingly out of nowhere»[1] and interrupts reality, destabilizing the structures that sustain it. On the basis of this premise, Žižek posits the planet’s possible crash as the event of the film and explores how the characters experience it by means of the frame through which each of them understands his or her surroundings.[2] The arrival of an event inevitably alters our way not only of understanding reality but of relating to it.

In the context of contemporary art in Mexico, the event of the moment is not the collision of a «massive blue telluric planet»[3] with Earth, but rather a work of art by Jill Magid (U.S.A., 1973): The Proposal (2014-2016), a ring with an uncut 2.02-carat blue diamond, made out of 525 grams of the architect Luis Barragán’s ashes (Mexico, 1902-1988).

The Proposal is part of an extensive multimedia project by Jill Magid, The Barragán Archives, which began in 2013 and through which the artist has researched the management of the archive of the famous architect—the only Mexican to have received the Pritzker Prize—in order to delve into the exercise of control over his legacy. Luis Barragán’s archive is divided into two parts: his library and personal archive are managed by the Fundación de Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán A.C. in conjunction with the government of the State of Jalisco, and are located at Casa Luis Barragán in Mexico City, formerly the architect’s home and studio, which was established as a museum in 1994. Meanwhile, his professional archive of drawings, sketches, blueprints, manuscripts and preparatory materials is managed by The Barragan Foundation (sans accent), which was established with the support of Vitra, a Swiss company that produces designer furniture. The professional archive is found on Vitra’s campus in Birsfelden, near Basel. This archive was acquired in 1995 by the owner of Vitra, Rolf Fehlbaum, and was supposedly an engagement present for his current wife and director of The Barragan Foundation, the Italian architectural historian Federica Zanco. Through Barragán’s archive, Magid questions the organs of power that regulate access to this collection of historical records, as well as the complexity of authors’ rights in the present day and how all this can come to determine an artist’s legacy.

The Barragán Archives has entailed an arduous investigation lasting nearly four years on Magid’s part. This research has been manifested in the creation of various works and exhibitions.[4] Nevertheless, the project has reached a turning point with the piece The Proposal—and the exhibition of the same name[5]—since the work encompasses not only the ring, but also a daring proposition: Magid has offered it to Federica Zanco in exchange for opening Barragán’s professional archive to the public in Mexico:[6] «the body for the body of work.»[7]

On August 1, 2016, one week after the opening of Ex-Voto at the Mexican gallery LABOR,[8] Alice Gregory published the article «The Architect Who Became a Diamond» in The New Yorker.[9] This captivating chronicle of Magid’s project triggered a series of polemical articles about The Barragán Archives, written by a variety of figures from different fields, including some who are foreign to the art world: the dozen or so important pens included those of the writer and journalist Juan Villoro,[10] the writer and political analyst Jesús Silva-Herzog Márquez,[11] and the curators Daniel Garza-Usabiaga[12] and Cuauhtémoc Medina, both of whom double as art critics.[13] These articles reveal the social constructions that rule over the systems inhabited by these writers—whom I have now joined—and reflect the different ways in which we frame reality. Some, like myself, approached the work with amazement, while others did so with disgust or even horror. As in Melancholia, we are presented here with an event: The Proposal as part of the art project The Barragán Archives. Each of us confronts this event through the different lenses of our own histories and fantasies, which determine how we construct life. Is it about the fantasy of Barragán’s image? About the content of the archive? About art itself? Or could it be about the fantasy of two women, Jill Magid and Federica Zanco?

One of the positions taken by critics focuses specifically on The Proposal and problematizes its form. This is the case in the texts of Villoro and Silva-Herzog Márquez, who object to the process that led to the creation of this ring and regard it as profaning the architect’s final resting place and his patrimony itself. If the origin of this position were religious in nature—although none of the authors express it this way—there would be nothing more to say, since by definition faith cannot be refuted.

Curious to explore another way of seeing and understanding the exhumation of Barragán’s ashes, I visited The Proposal at the San Francisco Art Institute. I spoke with Hesse McGraw, Vice President for Exhibitions and Public Programs and curator of the exhibition—which will be on display at the Walter and McBean Galleries until December 10—who explained how the artwork not only exhumed Barragán’s remains, but also opened new possibilities for his legacy. McGraw spoke of the double meaning of the word «exhume»: the first definition is indeed related to disinterring human remains, but the second is «to unearth, bring to light.»[14] As McGraw put it, «the idea that this project is bringing the archive and the legacy once again as topics of conversation, in ways that hadn’t been done before is quite powerful.»[15] He sees The Proposal through a frame of artistic creation, without religious connotations. Exhuming Barragán’s ashes in order to take 525 grams of them to be turned into a work of art constitutes a sort of poetic and political alchemy.

The negative reactions to The Proposal also include critiques that go beyond the exhumation and focus on the symbolic qualities commonly attributed to diamonds. This argument focuses on the idea that a diamond represents glamour and ostentatiousness, attributes that were foreign to Barragán’s ideals. As Villoro writes, «The master of austere spaces is now a banal adornment. What explains this grotesque act of recycling?»[16] Perhaps it can be explained through the history of art itself: an object’s symbolism changes when it is inserted into the art system. We need only to think of Marcel Duchamp’s The Fountain (1917). Indeed, at that time—almost a century ago—Duchamp’s work provoked great polemics. Critics labeled his readymades as immoral and vulgar, and even regarded them as acts of plagiarism.[17] Nevertheless, that urinal did end up becoming a fountain, and Duchamp did change the course of art history, opening the path for conceptual art. Perhaps the time is right to reread Octavio Paz’s reflections on these issues in Marcel Duchamp or The Castle of Purity (1968) and Marcel Duchamp, Appearance Stripped Bare (1973).

Just as Duchamp’s urinal has become a fountain, Magid’s ring can no longer be seen as just a piece of jewelry. In my opinion, the diamond shines not with an arrogant or fatuous luminosity but rather with a radiance that shows us the shadows of our time. Before traveling to San Francisco, the exhibition The Proposal was in St. Gallen, Switzerland, at the Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen. In neither of these two cities did it prompt the commotion that arose in Mexico. One could argue that this was because the architect-turned-diamond was neither Swiss nor American, and that the reaction might have been different if the ashes in question had belonged to Frank Lloyd Wright or Le Corbusier. Or might it be that the project touches on the weight of Mexico’s colonial history, which perhaps makes it difficult to consider an exhumation from a standpoint that is neither moral nor religious? At the same time, The Proposal evidently does not appeal to the purely formalist desires of many people in Mexico. One need only survey the history of art to note its transformations, which are nothing more than reflections of the evolution of humankind itself.

Is it a coincidence that just a few weeks ago the Vatican publicly prohibited the ashes of the deceased from being turned into jewelry or scattered in nature? Or is it possible that a «mere» work of art could have the power to penetrate the thick walls of the Holy See? We must recall that one characteristic of Magid’s own artistic practice has been to subvert the established order by undermining some of the most infamous systems of authority, like the New York Police Department, the Dutch intelligence agency, and other surveillance regimes. The power of art…?

To return to the alleged commercial value of The Proposal, in the article «Las cenizas del arquitecto» [The Architect’s Ashes], Silva-Herzog Márquez writes, «A world that commoditizes everything is a world that makes everything into an artistic pose […]. Everything is a commodity for the discourse of conceptual art, so meager in art, so poor in concept, and so abundant in empty patter.»[18] It suffices to examine Magid’s project a bit more closely to realize that the ring is anything but a commodity; it is poetry. There is a legal contract that stipulates that the piece can never be sold; therefore its importance is not monetary. It is an offering that can only be received by Federica Zanco. The Proposal can no longer be seen as a piece of jewelry, but must be regarded as a work of art whose value goes beyond the domain of the economic, because a ring also symbolizes a commitment, in this case a commitment to art.

It would seem that The Proposal has become something of a threat, like the planet that could crash into Earth in Melancholia. A reflection of a fear of an «otherness» in which an object cannot be conceived beyond its form? But what if that form which offends so many people was necessary to cause the effect that has been unleashed? Moreover, what happens if we regard the selection of an engagement ring as a deliberate decision on the artist’s part? Far from being a «naïve» gesture, I see Magid’s determination to turn Barragán’s ashes into a diamond—something inadequate indeed for representing the architect—and not into an object associated more closely with him, as a conscious choice. She masters the double signification of the ring: at once superfluous and indispensable, illusory and undeniable, mournful and promising. Magid knew that only a symbol so distant from Barragán would be capable of dislocating us, precisely through its irony, which inevitably forces us to regard it from another standpoint. As the titular planet in Melancholia approaches Earth, one character attempts to calm another down by telling her to look at it through a wire hoop, and then to look at it again ten minutes later to see that it has gotten smaller, which ends up proving that Melancholia is moving away from the Earth.[19] If we were to peer through that wire hoop ourselves and point it at the ring, we would see that because of these polemics, the diamond has grown exponentially.

It is thanks to The Proposal that we arrive at the archives of Luis Barragán, an artist’s bequest to his world, to his century, and to the core of Magid’s project, which raises the question of an artist’s legacy, «how it is constructed, manipulated, consulted, and owned.»[20] Another question might be: what responsibilities should befall an institution that takes ownership of a legacy, not only vis-à-vis the artist, but also vis-à-vis the public? Magid’s proposal is aimed not simply at getting Federica Zanco to literally open the archive, but also at getting each of us to question our way of relating to structures of power, and even with the possibilities and limits of art. It is likely that Magid is aware that her own practice cannot escape the realm of commerce, since even though The Proposal itself cannot be sold, her practice has been commoditized through the galleries that represent her. Thus, it does not seem far-fetched to me that through The Barragán Archives Magid should come to question her role in the system and recognize her own complicity within it.[21]

The Proposal not only interrupts, but also erupts. It creates ruptures in an already fractured system that inevitably confronts us with our own fault lines, lacks and narrow ways of framing what surrounds us. We are faced with what Žižek calls «unknown knowns»: «the disavowed beliefs and suppositions we are not even aware of adhering to ourselves.»[22] Thus the ring becomes an Event, «the exposure of the reality that nobody wanted to admit, but which has now become a revelation, and has changed the playing field.»[23] The controversy that it created is now part of the work. Each one of these articles has become a star in the constellation of The Barragán Archives.

There is something vital that escapes all of this. In his speech upon receiving the Pritzker Prize in 1980, Barragán said, «It is alarming that publications devoted to architecture have banished from their pages the words Beauty, Inspiration, Magic, Spellbound, Enchantment […].»[24] Is it not the case that the polemical ring has a touch of each of these words, so highly valued by the architect himself? After all, as Jill Magid says, «[…] the most radical tool of pragmatism is poetry.»[25]

[1] Slavoj Žižek, Event: A Philosophical Journey Through a Concept (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2014), p. 4.

[2] Ibid, pp. 16-20.

[3] Ibid, p. 18.

[4] A chronology of exhibitions, in reverse order: The Proposal, San Francisco Art Institute, Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco, 2016; Ex-Voto, LABOR, Mexico City, 2016; The Proposal, Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Gallen, 2016; Woman with Sombrero, Museo de Arte Zapopan, Guadalajara, 2014; Quartet, South London Gallery, London, 2014; Homage, RaebervonStenglin, Zürich, 2014; Woman with Sombrero, Yvon Lambert, Paris, 2014; Woman with Sombrero, Art in General, New York City, 2013; Der Trog, Art Basel Parcours, 2013.

[5] The Proposal was commissioned by the San Francisco Art Institute. The exhibition was curated by Hesse McGraw, SFAI Vice President for Exhibitions and Public Programs, and organized with Katie Hood Morgan, Assistant Curator and Exhibitions Manager.

[6] Magid wrote in her letter of proposal to Federica Zanco: «The ring will always be available to you, and to you alone, whenever you are ready to open the archive to the public in Mexico.»

[7] Jill Magid, press release for The Proposal, San Francisco Art Institute.

[8] At LABOR—the gallery that represents Magid in Mexico, and which is located across the street from Casa Luis Barragán—Magid presented Ex-Voto (from July 23 to September 3, 2016). This exhibition did not show the piece The Proposal, but rather «two new sculptures, her video work The Exhumation, and a series of ex-votos. An ex-voto, often realized as a narrative painting or tin plaque, is a votive offering presented to a saint or divinity in fulfillment of a vow. At the exhumation of Barragán’s ashes from Rotonda de los Jalisciences Ilustres (Rotunda of Illustrious Persons from Jalisco), Magid made Barragán a votive offering: a pure silver horse, equivalent to the 525 grams of his ashes she removed from the urn, which was permanently placed back into it. Magid’s Ex-Votos, a series of four painted tin horses, thank the Barragán family, the Government of Jalisco, the silver horse and the diamond, made solely from Barragán’s remains. A fifth horse will be produced when and if the ring is accepted.» (Excerpt from the press release for the exhibition, available online at <http://www.labor.org.mx/en/jilll-magid-ex-voto/>.)

[9] Alice Gregory, «The Architect Who Became a Diamond,» The New Yorker (August 1, 2016), pp. 26-33. This article appears in the electronic version of the same issue under the title «Body of Work.»

[10] Juan Villoro, «Anillo de compromiso» [Engagement Ring], Reforma (August 5, 2016) and «De vuelta a las cenizas» [Back to Ashes], Reforma (August 12, 2016).

[11] Jesús Silva-Herzog Márquez, «Las cenizas del arquitecto» [The Architect’s Ashes], Andar y ver: el blog de Jesús Silva-Herzog Márquez (August 11, 2016). Available online at <http://www.andaryver.mx>.

[12] Pamela Ballesteros in interview with Daniel Garza-Usabiaga, «La implicación del archivo Barragán» [The Implication of the Barragán Archive], GASTV (August 2016). Part one is available online at <http://gastv.mx/entrevista-daniel-garza-usabiaga-la-implicacion-del-archivo-barragan/> and part two at <http://gastv.mx/entrevista-daniel-garza-usabiaga-la-implicacion-del-archivo-barragan-parte-ii/>.

[13] Cuauhtémoc Medina, «Un anillo embrujado» [A Bewitched Ring], Excélsior (August 19, 2016), available online at <http://www.excelsior.com.mx/opinion/columnista-invitado-comunidad/2016/08/19/1111937>.

[14] «exhume, v.» OED Online. December 2016. Oxford University Press. <http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/66211> (accessed February 3, 2017).

[15] Hesse McGraw, conversation with Othiana Roffiel, November 2016.

[16] Villoro, op. cit.

[17] MoMA Learning, «Marcel Duchamp and the Readymade,» available online at <http://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/dada/marcel-duchamp-and-the-readymade>.

[18] Silva-Herzog Márquez, op. cit.

[19] Žižek, op. cit., pp. 18-19.

[20] Jill Magid, «Locating Legacy: Jill Magid in Conversation with Nikolaus Hirsch and Hesse McGraw,» in The Proposal: Jill Magid, edited by Nikolaus Hirsch, Carin Kuoni, Hesse McGraw and Markus Miessen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), pp. 6-7.

[21] The preceding reminds me of something Andrea Fraser wrote: «[…] the institution is inside of us, and we can’t get outside of ourselves.» Fraser, «From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique,» Artforum (September 2005): 282.

[22] Žižek, op. cit., p. 11.

[23] Ibid, p. 14.

[24] Luis Barragán, «Ceremony Acceptance Speech,» The Hyatt Foundation / The Pritzker Architecture Prize, 1980. Available online at <http://www.pritzkerprize.com/1980/ceremony_speech1>.

[25] Magid, op. cit., p. 15.

También te puede interesar

12° BIENAL DE SHANGHÁI. PROREGRESS: ARTE EN UNA ERA DE AMBIVALENCIA HISTÓRICA

Curada por Cuauhtémoc Medina, y con la co-curaduría de María Belén Sáez de Ibarra, Yukie Kamiya y Wang Weiwei, la 12° Bienal de Shanghái reúne a 67 artistas de 26 países –la edición con...

MARÍA LAURA ROSA Y JULIA ANTIVILO: CURAR E HISTORIAR LAS TRAMAS FEMINISTAS

El CNAC, en Santiago, presenta la primera muestra antológica de Polvo de Gallina Negra, colectiva pionera de arte feminista mexicano, y sus vínculos con el artivismo feminista latinoamericano. Mariairis Flores entrevista a las curadoras...

“MONUMENTOS HORIZONTALES”, DE MIGUEL BRACELI. UNA MEMORIA DEL FUTURO

Braceli parece echar luz nuevamente sobre Juárez, lo desnaturaliza derrumbando el homenaje, pero construyendo, en ese derrumbe, una representación metafórica y a escala de aquello que Juárez representa. Y el carácter efímero de este...