WHO WAS JUAN TREPADORI?

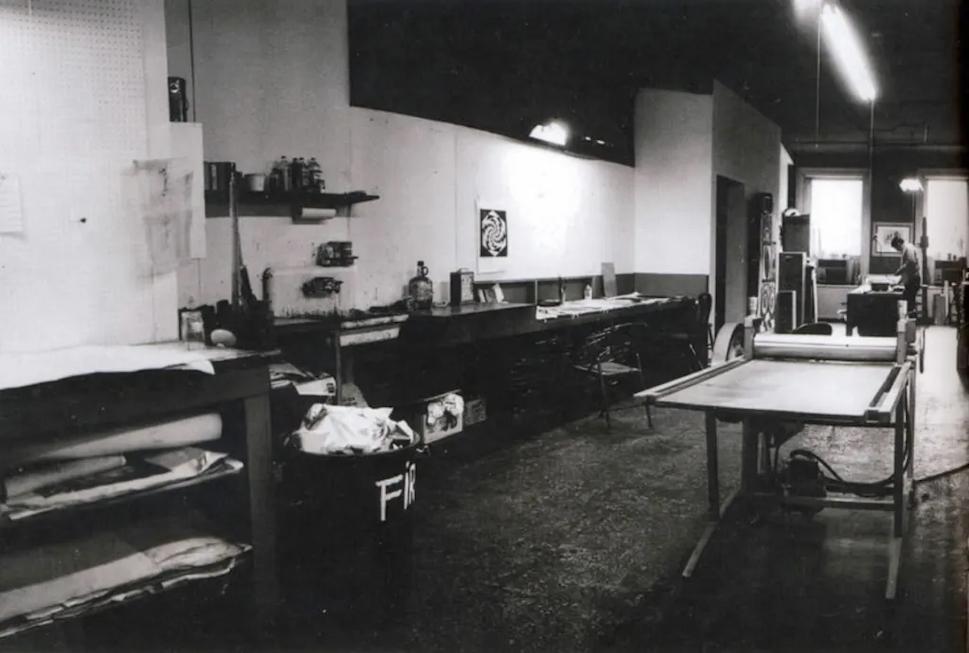

2024 marks the 60th anniversary of the New York Graphic Workshop (NYGW), the group of printmaking artists formed in 1964 by Liliana Porter (Argentina), Luis Camnitzer (Uruguay) and José Guillermo Castillo (Venezuela). Among the artworks that should be remembered are those of an artist completely made up by the group.

The life of the artist Juan Trepadori is fascinating.

So fascinating that it is said Juan Trepadori was born in Paragua, in Asunción, in 1939. He was a child prodigy and a piano virtuoso, but his musical dream was cut short when he was the victim of a car accident.

It is known that was the moment where he lost his parents and the mobility of his legs. But Trepadori’s life is so amazing, that despite ending up in a wheelchair he did not give up, and he decided to change music for art. It is said that, at that time, he was already living in Europe, in Lisbon more specifically, and he began to paint as a self-taught artist. He even took a printmaking course at the school of German-French artist Johnny Friedlander. It is said that during the 50s and 60s many Latin American artists went to the Atelier Friedlander in Paris. But of course, Trepadori took the course by mail, because he was not able to move.

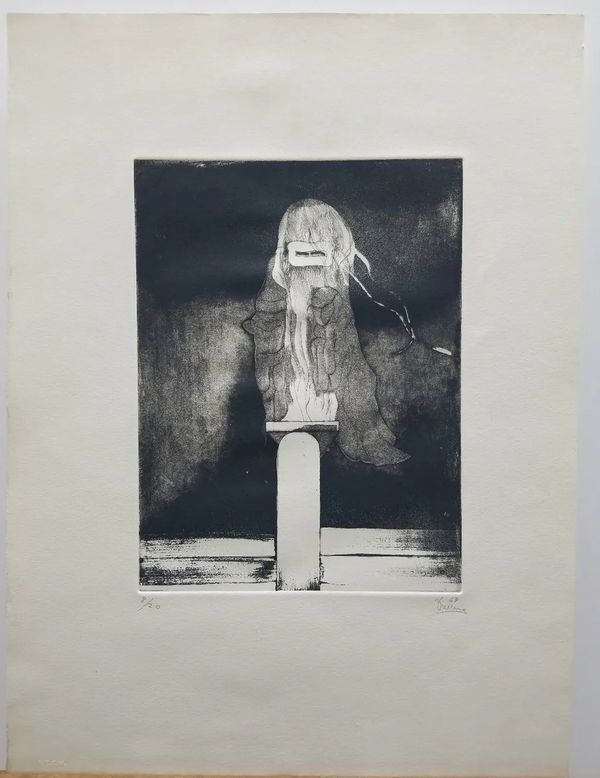

His works, colorful and vibrant, was light in the face of the darkness of a tragic personal history, “it is easy to think of it as an escape route,” says art historian Gina McDaniel Tarver in her article “The Trepadori Project” for the Blanton Museum of Art.

Juan Trepadori never left Lisbon, but surprisingly his works reached New York. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he appeared in several exhibitions by the group of artists of the New York Graphic Workshop (NYGW), and quickly began selling his prints to American collectors. “In fact Juan was very good, financially speaking, much better than us,” recalls Luis Camnitzer, one of the members of the Workshop.

It is also said that in his desire to help young Latin American artists who had recently arrived in New York, in 1969 he began to donate 24% of his sale profits to the Fandso Foundation, created by members of the New York Graphic Workshop, a foundation that offered scholarships to study printmaking in the city. The last thing known about Juan Trepadori is that he exhibited his final works in 1973. After that moment, he disappeared.

The life of artist Juan Trepadori is so fascinating, that he was someone who never existed.

Juan Trepadori is an invention of the New York Graphic Workshop, the group of artists formed in 1964 by Liliana Porter, Luis Camnitzer and José Guillermo Castillo. “We wanted to redefine the concept of printmaking”, Porter recalls.

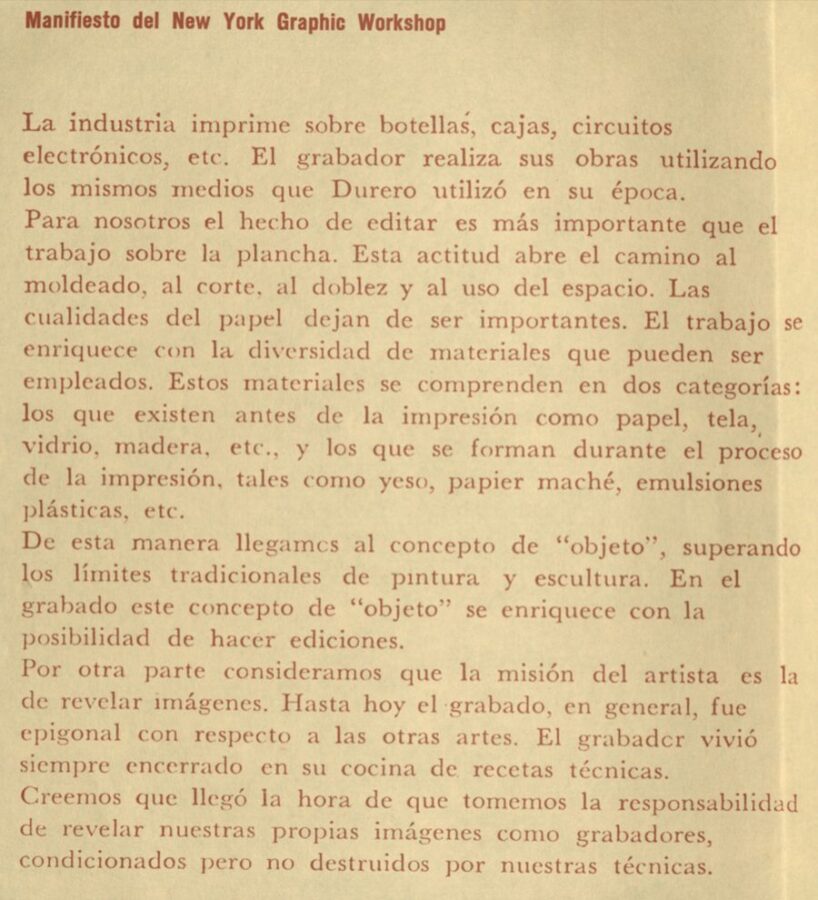

It is precisely in their first manifesto where they advocate for a new concept of printmaking that goes beyond working on plates and paper, and gives importance to the aesthetic dimension of editions. “The NYGW did not believe that a work of art had to be singular and unique in order to have artistic value, in fact, they recognized the creativity and generative possibilities of reproduction”, says art historian Rachel Vogel, “it is the viewer who gives the seal of originality, not the artist,” she continues.

The discourse at the time revolved around the idea of the “original print” and its codification was given by the need to differentiate between works of art and their copies within a market that tried to regulate fraudulent reproductions. On the other hand, McDaniel Tarver highlights how it was common in art magazines to find ads that encouraged collectors to “build a valuable collection made up of limited editions.” The fact is that pop and conceptual artists were contributing to the legitimization multiples within the market of plastic arts.

However, the NYGW was trying to move away from the label of conceptualism. “At that time the term conceptual art appeared, and we decided as a group that word was bullshit”, says Luis Camnitzer, “what we wanted to do was contextual art”. Voguel explains that, although the formal result of the NYGW works resembles that of their conceptualist contemporaries – minimalist aesthetics, use of text, instructions that request the participation of the consumer -, in the eyes of the group, the conceptual artists placed too much emphasis on idea of the artist as a mechanism to determine the work. By considering themselves “contextual” artists, they emphasized the reception side and not the creation side. That is, the consumer’s side and not the artist’s side.

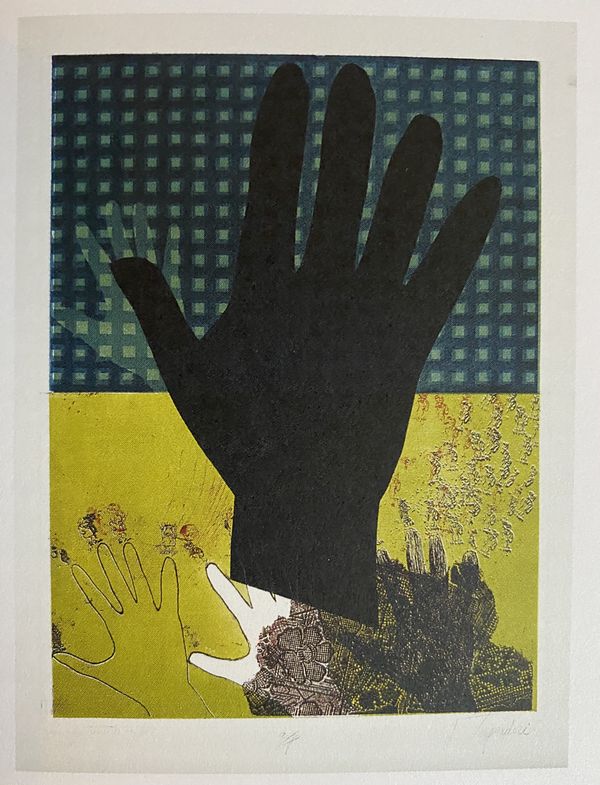

In this context, in 1967, Porter, Camnitzer and Castillo decided to create the first Trepadori under the title Three Hands Reaching the Sky. “My father was very funny, very witty, he had many ideas”, says Camila Castillo, José Guillermo’s daughter, “he always found a way to find a positive spin in what seemed negative. The creation of Juan Trepadori is an example of that”.

The idea of the group was to present a work of impeccable technique but void of meaning, which would compete in the annual exhibition of SAGA (Society for American Graphic Artists) where they could win up to 3,000 per work (more than $30,000 today), explains McDaniel Tarver. Then they would uncover the secret and expose the industry.

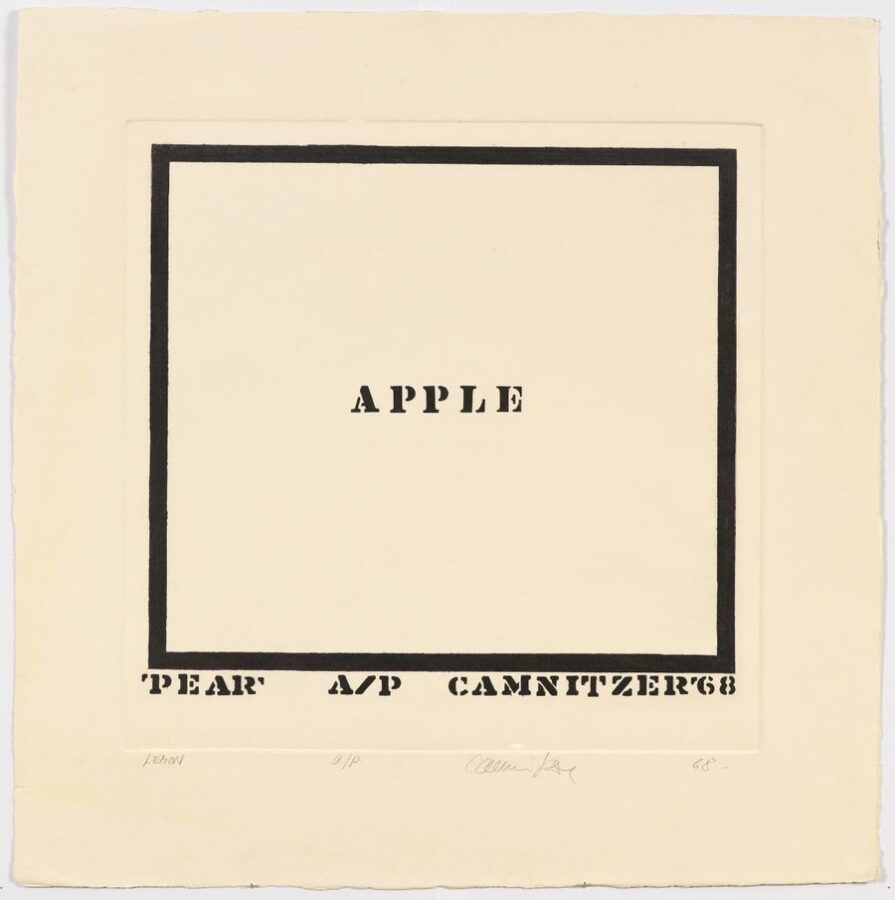

This way Juan Trepadori allowed the NYGW to play in a way that did not compromise their ideas on authorship, originality, and conceptualism. “The Print Council of America (PCA) said that a piece could only be an original if it was signed by the artist, but in this case, technically, there is no artist,” Vogel observes.

Before being able to submit any work, SAGA required artists to become members of the organization and create eight pieces. Neither Porter, nor Camnitzer, nor Castillo wanted to create an exhaustive portfolio of Trepadoris, so they put their plan on hold. But only until two years later, where Juan Trepadori would resurrect to help a friend in financial trouble.

In 1969, the Chilean-Spanish artist Gastón Orellana was travelling to New York from Spain. He brought with him several artworks that ended up being confiscated at customs and he did not have enough money to pay the fees. NYGW members then thought about selling copies of their work to help him. But the works that the NYGW was producing at the time were simply not selling.

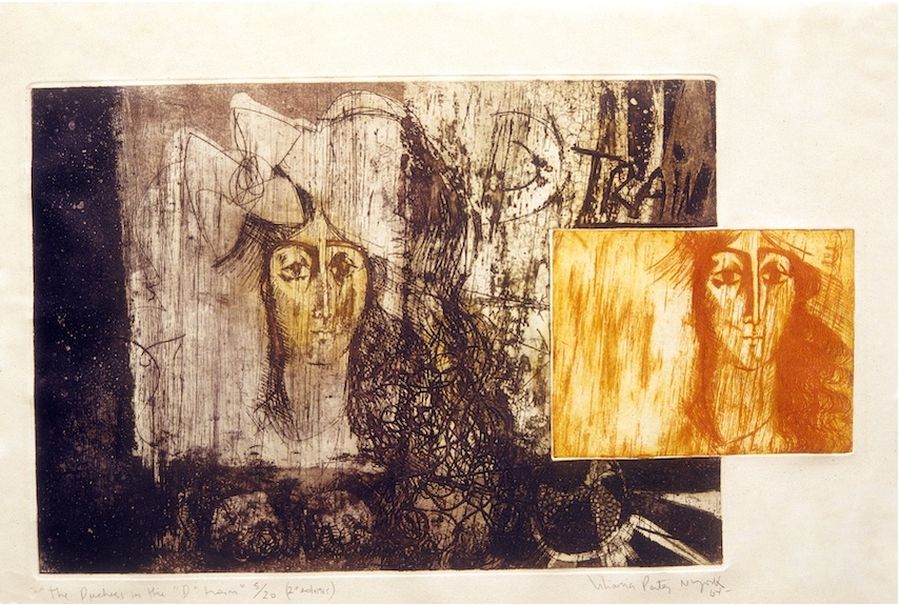

Before forming the NYGW was formed, Porter had made good money selling works such as The Duchess of Alba on the D Train, which, according to her art dealer, was more in line with the tastes of American consumers: color, naturalism, primitivism, folklore.

Trepadori’s works were intended to please the expectations of the market in which they found themselves. “Whether it was intended or not, viewers surely saw Trepadori’s works as representing Latin American identity. The norm was to anticipate a typical imaginary related to an indigenous culture,” says McDaniel Tarver. With that premise, the group decided to get to work and create works that were “easy” to sell.

And the truth is that the works under the Trepadori label were unequivocally inspired by a monolithic and stereotyped vision. “At that time everything was Diego Rivera and Diego Rivera. At that moment it seemed that they [NYGW] denied all that, what did they want to change about Latinidad?” says Dulcina Abreu, independent curator. “You can’t really change it, we are too diverse. There is room for tropicalism and for conceptualism,” she adds, “we are as great as the diversities in which we live, the languages we contain, the color of our skin and the texture of our hair. Art cannot be homogeneous”.

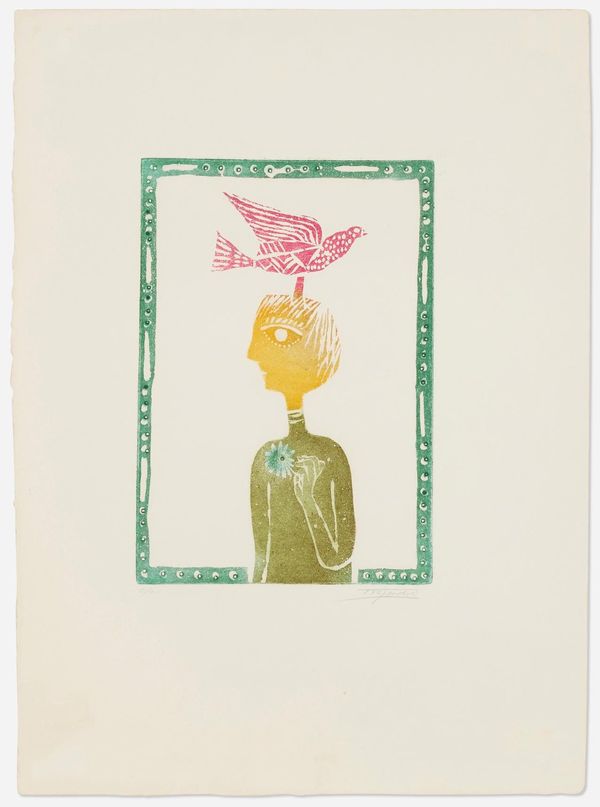

In her dissertation “Mutual Registration: Printmaking and/as Conceptual Art”, Vogel highlights how, even though the artists were not necessarily intending to invoke styles associated with Latin American artists, such references are evident in prints like Niño e Idea from 1969, which replicates in aquatint the flat shapes and white lines associated with Mexican woodcuts.

“This adds an additional layer to the NYGW’s criticism of the print market, pointing to its appetite for Latin American artworks only when they conform to collector’s mental image of what they “should” look like, with little regard for supporting Latin American artists”, she continues.

Later, the NYGW expanded Juan Trepadori’s idea into the Fandso Foundation. “They were kind of still playing with this idea of challenging institutions,” says Vogel, “but they do it by supporting the causes that they consider important.” In this case, the money raised from the sale of Trepadoris would go towards funding scholarships for Latin American artists at the Pratt Graphic Center.

The rules of the Foundation were, among others, that: Juan Trepadori’s function, as an extension of the Foundation, was to help artists, mainly those from Latin America, during times of economic difficulty. Juan Trepadori should not be used in any case that was not justified as a legitimate economic need. The profits would be distributed as follows: 23% for the artist who designed the work, 24% for the scholarship, 40% for the printer of Trepadori’s work, 5% for the manager (which would be Orellana), and 8% for the cost of materials.

The foundation would grant a small number of scholarships until 1970, including that of the Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino.

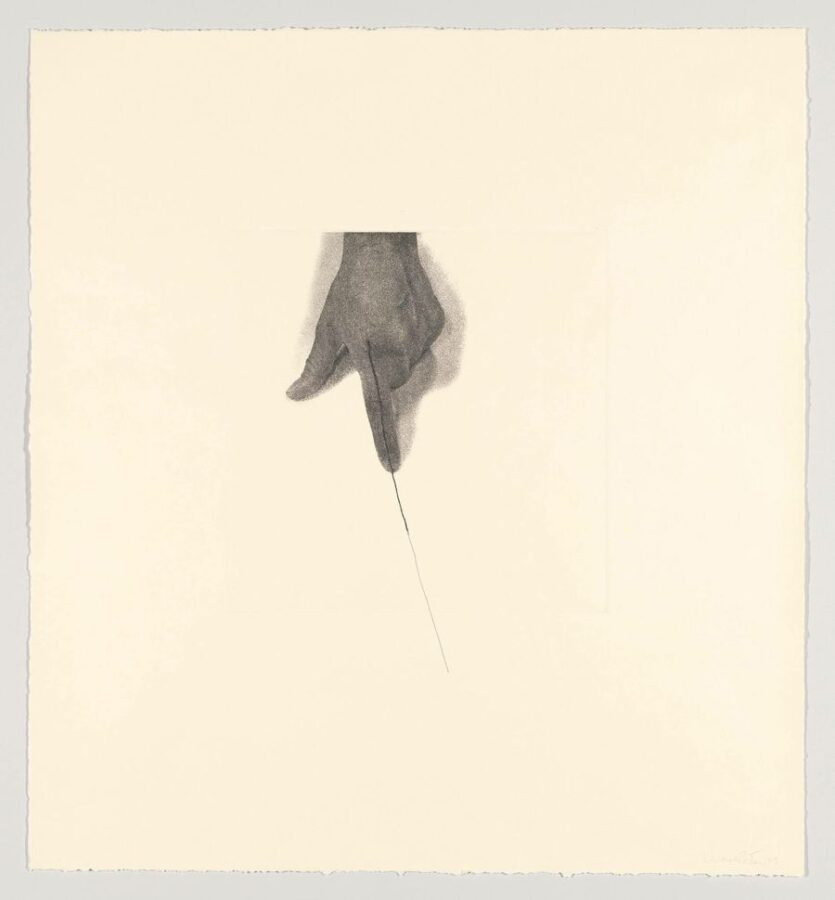

José Guillermo Castillo, Untitled, 1967 | Liliana Porter, The Line, 1973 | Luis Camnitzer, Lemon, 1968

Juan Trepadori’s project also ended up being a source of entertainment. Creating an alter ego allowed artists to escape intellectual rigor and create works in a context of entertainment. “Liliana [Porter] tells how people started creating Trepadoris and how much fun they had doing it” says Vogel, “making work that is not directly associated with your particular style, that doesn’t have your name on it, it gives a certain freedom outside the pressures of the art market.” The art historian adds that the fact that Juan Trepadori’s identity was kept a secret for so long distinguishes the NYGW from other conceptual artists of the time. There was an element of resistance to the industry, but its critical dimension was only known to those who were participating inside the joke. “Trepadori was a strategy to navigate and manage the contradictory position in which Latinamerican artists of the time found themselves. The project spoke of the pressures to conform to market demands, and yet, the NYGW, with its characteristic humor, managed to ensure that artists benefited without compromising their artistic practices,” Vogel concludes.

“Although I have my reservations with their interpretation of tropicalism and how they showed resistance to that style, at the same time I cannot say that I am so out of the loop that the NYGW was proposing in the 60s,” adds curator Abreu, “in the sense that I now benefit from how they educated a public that continued to look at Latin America with a colonial lens and expected all art to be only tropical.”

McDaniel Tarver details that among the invoices kept by Luis Camnitzer it is recorded that an art dealer paid up to $1,125 (about $11,760 today) for works by Juan Trepadori. A payment document from July 1969 reflects the purchase of 45 copies of four different works, that is, a total of 180 units at $6.25 each (about $50.57 today). When the art dealer asked to meet Juan Trepadori, the group had to make up a story to explain why it was impossible for Juan to meet in person. Gastón Orellana then devised the entire plot around Trepadori’s fateful accident, and from there his fascinating biography was created.

The last time a Juan Trepadori was sold was in January 2023 in Los Angeles, at the LAMA (Los Angeles Modern Auctions) auction house for $189. It was copy number 51 of 60 of Niño e Idea.

También te puede interesar

RETROSPECTIVA DE LUIS CAMNITZER EN EL MUSEO REINA SOFÍA

El Museo Reina Sofía, en Madrid, presenta a partir del 17 de octubre una retrospectiva de Luis Camnitzer (1937) que permite tener una visión global y contextualizada de la multifacética propuesta desarrollada por el...

EL PROGRAMA EDUCATIVO DE LA 10ª BIENAL DE MERCOSUR QUE HA DISEÑADO EL CHILENO CRISTIÁN GALLEGOS

Entre el 8 de octubre y el 22 de noviembre de 2015 se realizará la 10° Bienal de Mercosur en Porto Alegre, Brasil, bajo el título de Mensajes de una Nueva América. La curaduría de esta edición está…