DO WOMEN STILL HAVE TO WEAR GORILLA MASKS TO BE LISTENED?

ON THE 35TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE GUERRILLA GIRLS’ MET ICONIC POSTER

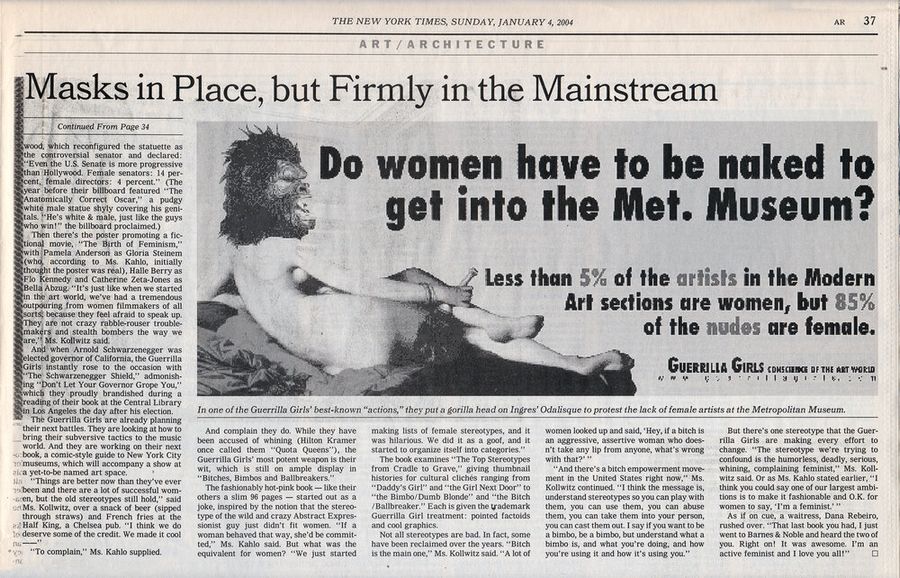

The Guerrilla Girls have had an impact on the New York art world since they emerged in 1985 with a poster that exposed gender disparity at the Museum of Modern Art. Internationally renowned, they have created a brand around their gorilla masks and the imagery of their most famous artworks. Since then, they have declared themselves the “conscience of the art world”, and publicly exposed names and uncomfortable numbers for art institutions. Through their posters, they highlight the discrimination faced by women in the art world, something for which we are all responsible: museums, curators, educators, universities, critics, researchers, art dealers, galleries, auction houses, collectors, and more.

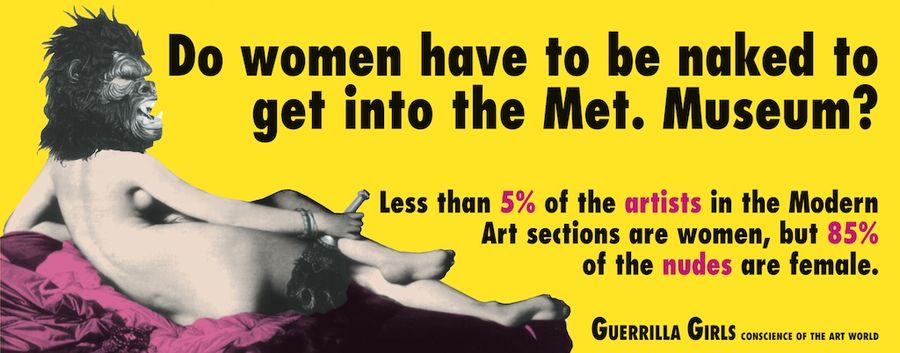

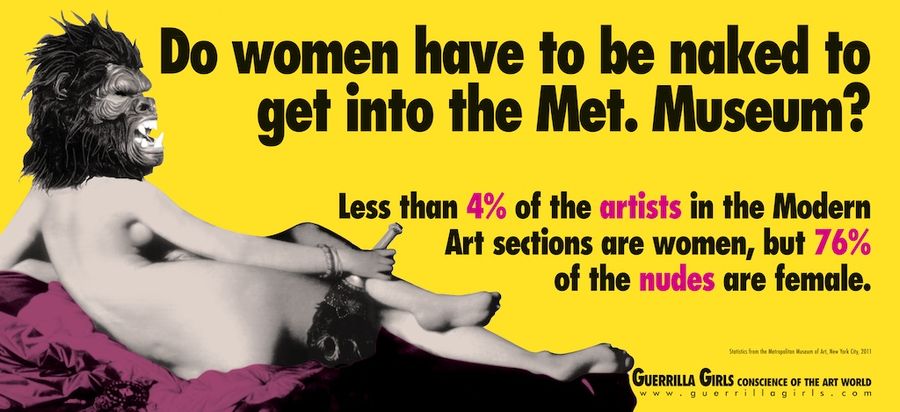

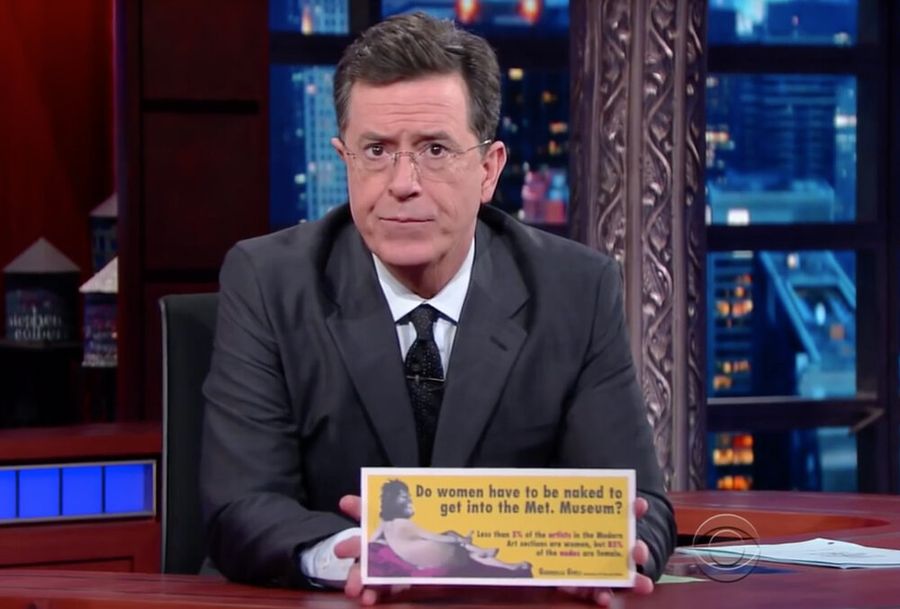

This essay specifically focuses on the 1989 poster “Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?”—a work that the Guerrilla Girls describe as “the poster that changed it all.”[1] An iconic poster that turns 35 in the spring of 2024, the perfect occasion to commemorate International Women’s Month.

The gorilla-masked odalisque

The artwork is titled Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum? and dates back to the year 1989. It is an 11 x 18-inch lithograph that, ironically, now belongs to the Met.[2] As a limited print, it is also part of other branded collections.

The piece features a striking design typical of the ‘80s with a significant conceptual content. The first thing that catches the eye is the nude depiction of a woman with a long spine, wearing only a gorilla mask that seems incongruous with the stylized body in a sensual pose.

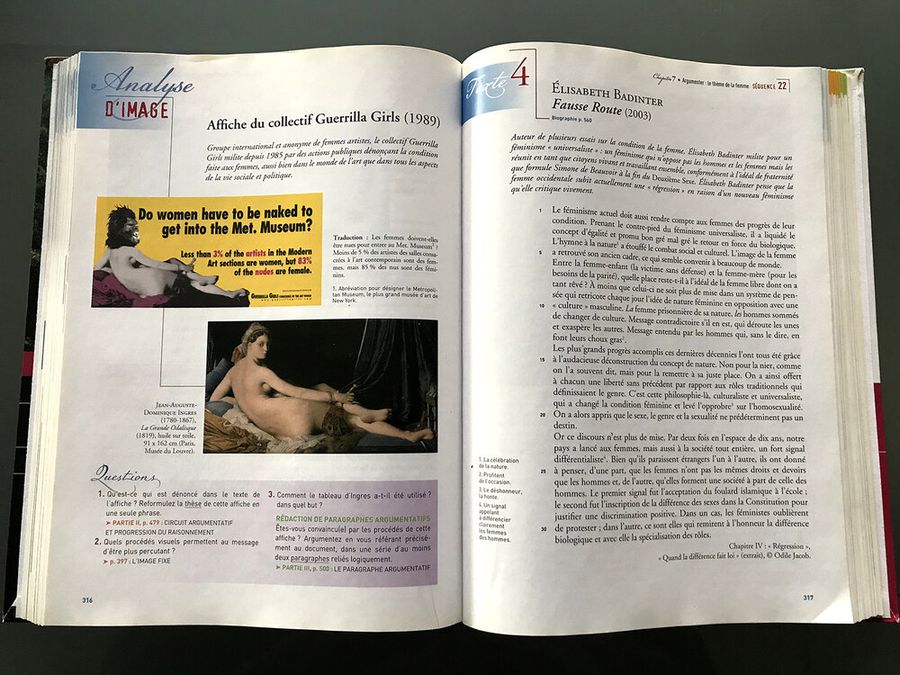

It is an appropriation of the 1814 painting Grande Odalisque by the French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a seminal work in the construction of the ideal of feminine beauty. This piece, from a canonized male master of late French Neoclassicism, turned out to be a smart choice by the Guerrilla Girls.

On one hand, the odalisque is a product inherited from the patriarchal system of the artistic academy (and also orientalist), so it carried in its iconicity the symbolism of that which the artists wanted to directly confront. This point is emphasized by Anne Teresa Demo:

By appropriating Ingres’s odalisque, the Guerrilla Girls illustrate how history can be re-presented. Yet in order to represent their vision of idealized female beauty, the Guerrilla Girls must not only appropriate the odalisque image but also mark it. Ingress odalisque is a classic symbol of patriarchal art; by defacing it, the Guerrilla Girls use the odalisque to critique the very institutions that canonize such images. Their juxtaposition of symbols produced by the dominant (male) culture with feminist imagery call into question the ideological construction of idealized femininity as submissive.[3]

On the other hand, the odalisque is not only a well-known image but also a back-facing nude. Perhaps, this was considered as part of the strategy to circumvent potential censorship for showing frontal nudity. As will be detailed later, the piece was subjected to censorship not once, but twice, despite being a relatively modest nude compared to other alternatives that could have been chosen. For instance, Manet’s Olympia might have been deemed potentially provocative if used in place of the odalisque.

Additionally, from a design perspective, Grande Odalisque also allowed for the ease of occupying space with more concentration on the left side and the lower half, tracing a diagonal that guides the viewer’s gaze through the woman (something Ingres was already aware of). This allowed the Guerrilla Girls to effortlessly incorporate easily readable typography within the composition, in accordance with the principles of graphic design and the viewer’s eye movements. Pop colors accompany this intervention of the masterpiece, rendering it in saturated pink and yellow hues, which add to the intended incongruity of the image-background.

Speaking of incongruities, it’s time to revisit the visual device of the gorilla mask, which obscures the face of the beautiful nude woman. The use of the mask is the distinctive mark of the Guerrilla Girls, who play on the pun of the subtle pronunciation between the homophones “guerrilla” and “gorilla” to create a visually impactful and humorous element that captures the audience’s attention.

The Guerrilla Girls use these masks to remain anonymous and present themselves for lectures at museums, universities, and other venues that have invited them for decades to engage with the public. Their performance involves evading questions about their identity, organizational structure, and any inquiries that divert attention from the artwork’s message towards their identities[4] or other details irrelevant to their purpose.

Kerry O’Neill points out a redefinition of anonymity, where it is exploited as an element of mystery and power:

In contrast to the history of female artistic expression, where anonymity was often the only recourse, the Guerrilla Girls use anonymity strategically to gain power. Members can be anywhere – even within the New York art establishment, subtly affecting decisions. The director of a gallery could have a studio assistant or secretary who is a Guerrilla Girl and not even know it.[5]

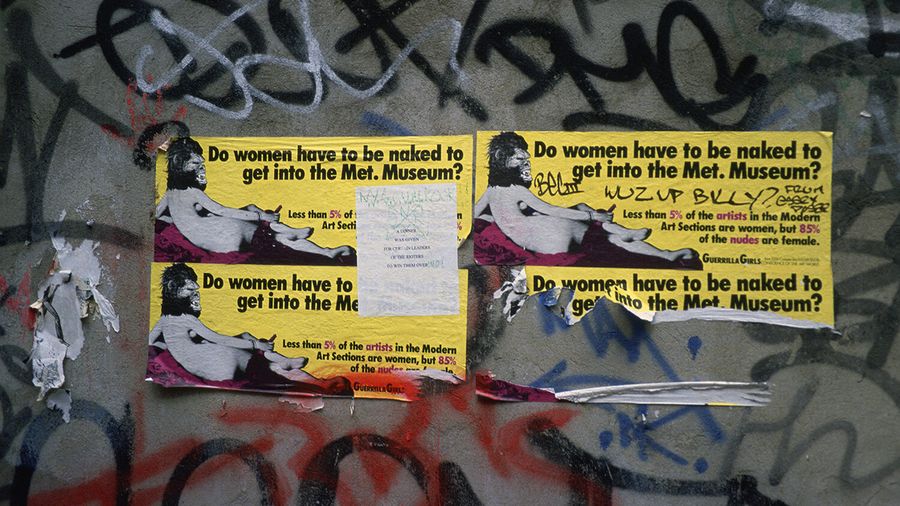

The gorilla mask also serves as a protective measure against potential reprisals that the members of the group may face, given that they are women artists and professionals in the art and museum fields. More than just their names and professional careers, their physical integrity was also at risk at some point in the guerrilla tactics. This is how they transitioned from the romanticized image of women with gorilla heads vandalizing the walls of SoHo at night to the economic possibility of hiring male workers to paste posters for them.[6]

Roberta Smith contributes to the discussion: “Their anonymity, while protecting them from retaliation, also means that whatever power they gain cannot be recycled into individual careers.”[7] This is how the fame of their modus operandi began to take shape, in Guerrillaesque fashion:

They required this interview procedure: All inquiries were to be left on the office answering machine; members returned calls at unknown days and times. (…) Over the years, members have conducted interviews with dozens of publications and have publicly appeared – a la gorilla masks – in panel discussions and in lecture halls of universities and museums around the country.[8]

And among many other reasons, the gorilla mask is the personal signature of these impersonal characters. It is what allows them to be attention-grabbing, readable, heard, praised, or criticized. Putting it on Ingres’ beautiful odalisque is a sacrilege to the grand and official(ized) History of Art.

Another important element in the poster is, of course, the title and the statement that straightforwardly displays the statistics of a powerful institution in the art world, pointing it out as the direct target of a shameful critique. Instead of traditional political arguments that might bore the viewer, the artists pose a provocative question (“Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?”), followed by indisputable numbers.

Their statistical strategy denounces: “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.” They sign as “Guerrilla Girls, Conscience of the Art World.” The naming and shaming of individuals are part of their guerrilla practice, and they have thus exposed male artists, galleries, museums, and critics who do not provide a space for women artists in their domains.

This method is highly effective in capturing the audience’s attention and guides the viewer in the following way:

After leading viewers on, or rather toward, one way of conceptualizing how women artists “get into” the Met, the group abruptly shifts the frame. The dramatic margin of difference between the percentage of women artists exhibited and the number of nude female figures displayed foregrounds the legacy of objectification within the artistic canon. Historically, women have been limited to three roles: muse, model, or object. The suggestion that, even in 1989, a woman has better chances of appearing on gallery walls as a nude model rather than an artist dramatizes the art world entailments of institutionalized sexism.[9]

On a communication level, according to Stephannie L. Rhyner, this poster goes beyond being merely satirical to be “laden with meta-communication that forces the viewer to move beyond merely looking and forces them to question and reinterpret how they see institutions, stereotypes, and art history.”[10] Meanwhile, a former target and later ally of the Guerrilla Girls, art critic Roberta Smith, states that their hit-and-run poster campaign is “confrontational without prescribing behavior.”[11]

After this formalist and interpretative reading of the work, it is possible to proceed to contextualize it within its historical moment. Using primary sources, a chronological timeline of the history of this artwork will be established.

Chronicle of an Announced Censorship

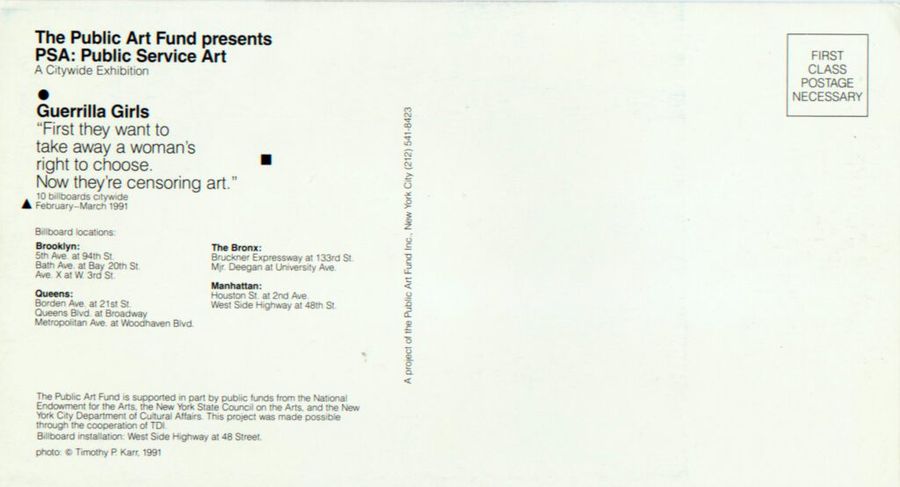

The genealogy that can be traced of the work under study begins when in 1989 the New York Public Art Fund commissioned the Guerrilla Girls to design a poster to publish it in billboard format.

By that time, the Guerrilla Girls had been operating on the streets of New York for almost five years, and had already produced 30 posters on the streets of the art districts.[12] For this occasion, they took the Met as their target, in the words of “Frida Kahlo”,[13] one of its founders:

One Sunday morning, a group of us went to the Metropolitan Museum with little notebooks. We were going to count naked bodies and female artists. It was only when we hit the 19th century, that early modern period, when sex replaced religion as the major preoccupation of European artists, did we get our statistic: Only 5 percent of the artists were women, but 85 percent of the nudes are female.[14]

From this field research emerges the statement of the work Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?, in a context where female artists were underrepresented in museums, which were funded and managed by a white male elite. The artists asserted that the museums were documenting power structures, not art.

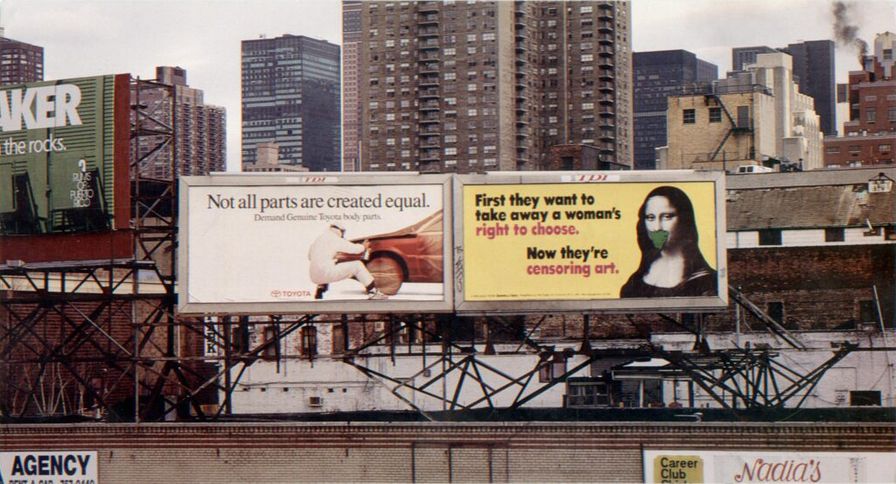

The Guerrilla Girls submitted this poster to the Public Art Fund, which marked the first censorship of this artwork. The institution requested a change to the proposal, citing it wasn’t “clear enough,”[15] and without further explanation, rejected the idea. The artists altered the design to a slightly more accommodating one, appropriating the image of the Mona Lisa with similar pop elements to those applied to the odalisque, accompanied by a message on a different topic.

One of the founders, “Gertrude Stein,” recounts the situation: “In 1991 we did a billboard project at the invitation of the Public Art Fund, (…) with the image of the Mona Lisa with a fig leaf over her mouth. (…) This was after our first design, based on Ingres’s Odalisque, was rejected.”[16] This is also confirmed by the Public Art Fund:

This citywide billboard project by the Guerrilla Girls (…) is the fourth and final artwork of the Public Art Fund’s PSA: Public Service Art exhibition series. The Guerrilla Girls have created ten billboards that alert the public to the current threat of censorship and a woman’s right to choose.[17]

The impact of this work was a 10-month exhibition of billboards (from February 1 to March 31, 1989), with two posters located in Manhattan, three in Brooklyn, three in Queens, and two in The Bronx, as documented on the reverse side of a collectible postcard detailing the exact locations of the billboards.[18]

While we won’t delve into the content of this work, it is of interest because it was the result that, as a symptom, managed to please both the commissioner and the artists. This reconciliation was successful, and the project was realized in 1991. However, back in 1989, there still remained the question of what to do with the wonderful idea of the odalisque.

The rest is history, and we know that the artists paid to place the poster on a Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) bus. Although the exact duration of the poster’s circulation cannot be traced, we do know that it was in the spring of 1989[19] and that it was removed for the following reason:

The New York City Transit Authority decided the Ingres picture was kind of dirty, and ordered its removal from the bus. About its defeat, the group is sanguine, noting that the $2,000 for the poster came from money earned through gorilla appearances.[20]

“Gertrude Stein’s” account confirms it once again: “We refashioned it as a bus poster; it stayed up for a little while before the bus company canceled our lease, saying the image was ‘too suggestive.’”[21] Following a second censorship, the Guerrilla Girls made the final decision to print the poster on a large scale and return to plaster the streets,[22] as is their well-known method.

Meanwhile, the Guerrilla Girls were further solidifying their public image, garnering both critics and supporters with a diverse range of opinions. One of their most mentioned critics is gallery owner Mary Boone, who stated, “the whole art world is highly competitive and discriminatory, (…) but it’s discriminatory based on talent, not on gender. (…) The issue is not men versus women, the issue is really success versus failure.”[23] Boone elaborates:

Art dealers say prices for art are not based on gender, but rather on a hierarchy that places artists such as Picasso and Van Gogh on one level, [Jasper] Johns and Andy Warhol at another. The price is based on supply and demand, the accessibility and the desirability of the work and the artist’s audience (…). Very few command multimillion dollar prices.”[24]

Another female gallery owner, Diane Brown, also responded without fully grasping the structural issue that the Guerrilla Girls aimed to highlight when she said in her critique of the group: “I will never represent someone because they’re a woman or not represent them because they’re not a woman. That’s really not an issue on why I choose to represent an artist.”[25] Baltimore female artist Grace Hartigan, dismissed the Guerrilla Girls as “absurd”:

They’re not going to change anything. (…) There is the same level of discrimination in the art world as in society at large, but says excellence should be what matters. The Guerrilla Girls (…) want the right for women to be as mediocre as men… The best always rise.[26]

Some men also spoke disparagingly about the impact of the Guerrilla Girls. For instance, David Adams of Allan Frumkin expressed at the time that the art world had already improved dramatically for women in recent years, but refused to attribute this change to the Guerrilla Girls, stating, “there are people who have simply grown up a little bit, and have gotten a little smarter.”[27]

More examples of the controversy. David Leiber of Sperone Westwater, said he doesn’t know anyone who might make an immediate decision in response to Guerrilla Girl tactics. “Some galleries might show more women than others, but I think it’s a reflection of their tastes in different works, and not a reponse [sic] to a quota system,” he argued.[28] Also, Robert Buck, who was at the time the director of the Brooklyn Museum, spoke out against the group’s anonymity.[29]

On the other hand, the Guerrilla Girls gained important allies in the media. We already mentioned, for example, Roberta Smith, who in 1990 responded to all the previous arguments by saying that “it is tempting to believe that true talent will always make its way to the top. But the Guerrilla Girls have demonstrated that differences in sex and race can make talent rise at very different speeds.”[30]

One of the most important women in contemporary New York art, Marcia Tucker, founder of the New Museum, said:

I think they are telling the art world things it doesn’t want to know. Certainly the major museums must know on some level that what they do does not represent the actual composition of the art community. In my experience, over thirty years of being in this field, there are certainly as many women working as men – and there are at least as many interesting women as men.[31]

Eugenia Foxworth of Soho 20, a cooperative women’s gallery, said the Guerrilla Girls are “the innovators in starting a movement to get women and minorities into galleries that have not shown them before,»[32] and Bill Arning of White Columns believed “there’s a lot of peculiarity about the numbers when people percentage out who gets shown and who doesn’t. It’s helpful to have someone pointing that out. I think they have made a real difference.”[33]

The Gorilla Girls have “raised people’s consciousness,” in the words of Linda Shearer, who was the director of the William College Museum of Art and previously a curator at the Modern Museum of Art. While Lisa Phillips, who was curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, said “their poster project has been extremely effective in reorienting art-world thinking”.[34]

These opinions from figures in the art world were published in newspapers during the time when the poster Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into The Met. Museum? was being published, censored, and then reborn to vandalize the walls of New York. They are not necessarily comments specifically about this work, but they reflect the polarization that the Guerrilla Girls were creating at the very moment when the piece was gaining attention.

Wrong answers and one missed opportunity

Although the institutions that unintentionally contributed to the success of this campaign did not face direct repercussions, they did miss the opportunity to sponsor a work that became an icon of contemporary art.

Both the Public Art Fund and the MTA censored the piece, depriving it of the chance to reach the public on ten billboards and a bus. Not only were they unclear about their limits and expectations, but they also censored a work of art. However, these suppressions ultimately propelled the poster into the streets, increasing its impact on the people.

The Guerrilla Girls’ presence on the streets became so influential that, “while never intended as art, the posters are sometimes peeled off building walls by admirers, saved and even framed.”[35] History has taught us that the more control and surveillance are exerted, the more likely the system will encounter resistance from the other side that responds.

On the other hand, the Met Museum continued to be a fixed target for the Guerrilla Girls. The work Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into The Met. Museum? has been monitored by the artists, who have conducted surveys in the museum and updated the poster. According to the latest count, dating back to 2012, there have been shameful changes: a 1% increase in female artists and slightly more male nudes than before.[36]

The work was donated to the Met as part of a limited edition of prints in 2021. However, the piece is not currently on view. It was only displayed in a minor exhibition focusing on the museum’s print collection,[37] rather than in a feminist-themed exhibition.

Censored twice and then overlooked by the Met, the Guerrilla Girls are not the losers in this story. The consequences of this controversy for the artists were that their poster went viral in a pre-internet era, both within and outside the United States.

Moreover, the poster is displayed in several major museums such as the Tate, Whitney Museum of American Art, National Gallery of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), Dallas Museum of Art, Art Institute of Chicago, Nasher Sculpture Center, and Moderna Museet (Stockholm).[38] Additionally, the Guerrilla Girls are recognized in prominent texts on feminist art, with the piece featuring the odalisque serving as their introduction.

Beyond major collections and academies, the Guerrilla Girls also capitalized on this momentum to reach the mainstream audience. Their concept, indebted to pop art, successfully achieves its goal through the creation of merchandise featuring the artists’ works and their presence on social media. It is for these reasons that their collective project has remained vibrant to this day, not confined to museum archives and history books.

Undoubtedly, the primary beneficiaries of this controversy have been the local and international female artistic community. Within the art world, “the Guerrilla Girls have helped fuel an increasingly noisy debate about elitism in the art world, part of a larger debate, spilling out from universities, about whether racial and sexual biases have narrowed the understanding of history and culture.” [39]

With this debate, fundamental theoretical concepts of male-centered History of Art are also called into question. In the words of Kerry O’Neill:

The crusty soil surrounding the ideological barriers that define “art” and “art history,” is consequently cracking. The mere presence of this group in the art world, along with the growing momentum of the 20-year-old feminist art history movement, is raising the bigger and tougher questions: “What does it mean to say a piece of art has ‘masterpiece’ or ‘genius’ quality?” “Who defines quality, and what prejudice does it reflect?” And, the all-inclusive: “How has racial and sexual biases narrowed our understanding of history and culture?”[40]

An article published in The Washington Post, from the same period in which we sought the impact of our poster, mentions that the Guerrilla Girls’ campaign “shows signs of success. More women are getting into galleries, and major museums have held a few shows of female and minority artists.”[41]

After enumerating many improvements that women artists experienced during the first five years of the Guerrilla Girls’ existence, exactly when they created the Met poster, Roberta Smith had it clear:

The increase in talented younger women artists is not something the Guerrilla Girls can take direct credit for, but they have certainly increased the pressure among dealers to seek out work by women, and this in turn encourages young female artists.[42]

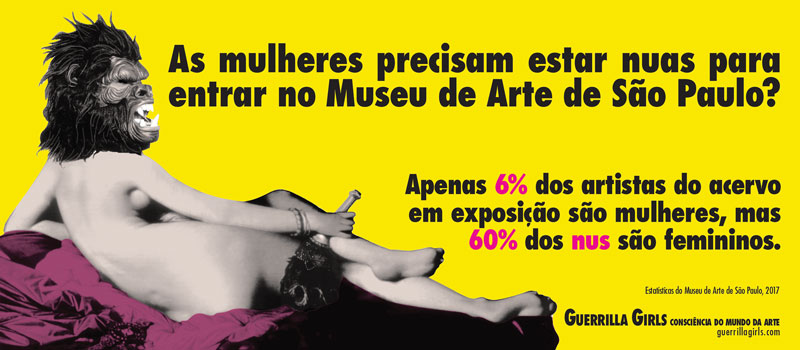

The Met poster has been replicated in many languages and reused to criticize museum collections around the world. It has also been recontextualized for new settings, reaching art consumers beyond just museums and galleries, entering to the mainstream world.[43]

An Institutional Mea Culpa

The Met gave one of the worst possible responses, choosing to ignore both the poster and the artists: “The Museum of Modern Art would not comment on them, and the Met did not return calls made by The Associated Press.”[44] We know that being ignored is worse than being criticized.

This response from the museum kept them safe from scandals they deemed “unnecessary” or “insignificant,” maintaining the museum’s status quo, which had nothing to lose directly from the existence and circulation of the poster.

However, an institution truly committed to social justice and the famous DEAI[45] principles could respond by taking responsibility for the situation denounced by the Guerrilla Girls. For instance, the museum could have started with a press release acknowledging the criticism in the artwork, and admitting that its role as a museum has contributed to the structural gender inequalities in Western society.

In this case, it was the museum’s duty to set an example of good practice, bearing the responsibility to disrupt with something shocking and innovative. Now that it had become the target of a high-impact social and media campaign, the museum should have used this statement to invite other museums, galleries, collectors, auction houses, and other art world stakeholders to review their collections and practices as institutions with social responsibility.

An immediate measure the Met could have taken is to purchase the artwork. We know it was donated by an intermediary on behalf of the Guerrilla Girls in 2021, which is embarrassing for a museum that allocates substantial budgets to acquiring works by established male artists. The museum has always played a role in the eternal cycle of “branding each other” with other male-white actors to maintain its normalized power as it is. Moreover, the museum not only should have bought the artwork but immediately displayed it in a strategically visible location. Self-targeting doesn’t harm the museum, but it is a direct way of taking responsibility for the problem.

The museum could have also established dialogue spaces with the Guerrilla Girls, female artists, academia, and the general public. This would have involved various educational programs of the quality and budget that the Met can actually offer. This way, the institution can mediate the discussion on its grounds and make more accurate decisions, with the perspectives of the counterparts being heard and considered.

As short and long-term goals, the Met could have assembled a diverse team of women experts in the necessary branches of art history and museology to lead a series of tasks such as: (1) Investigating the collection from a feminist perspective, (2) Reinterpreting the collection with the historical and theoretical information gathered, (3) Rewriting necessary descriptions and labels in its facilities and website, (4) Gradually bringing out all works by female artists from storage, (5) Creating statistics on female representation in the collection as a professional follow-up to the Guerrilla Girls’ poster, (6) Proposing acquisition policies that increase female representation, eventually reaching an ideally equitable quota.

This team should have also worked collaboratively with the community and diverse female artists who had wished to participate in the discussion. The museum should have demonstrated transparency with the decisions made and the results found from all these investigations and re-curation of the collection.

Please, let’s get over the 70s!

What will women need to continue doing to be represented in museums? This is a question that remains with the new generations who inherit the torch of succession. While the future of the situation at the Met cannot be avoided, collective and individual efforts contribute to pushing for change and feminist awareness.

The starting point is still the question posed in Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,”[46] where the author questions and challenges the traditional art historical narrative that largely excluded women from the canon of “great artists.”

She argues that the absence of great women artists is not due to any inherent “lack of talent or creativity” in women, but is instead a result of the social and educational structures that have systematically limited women’s access to artistic training, opportunities, and recognition. That is how societal expectations, gender roles, and institutional biases have contributed to the underrepresentation of women in the art world.

In addition to critiquing the historical exclusion of women, this seminal (ovular?) paper calls for a reevaluation of art history to recognize and appreciate the contributions of women artists. She encourages a more inclusive and diverse perspective in the study and interpretation of art, challenging the assumptions that have perpetuated the marginalization of women artists throughout history.

In this normalized patriarchal structural system, we cannot expect a 50% quota for female representation in the art world or sudden improvements in the training of young female artists. However, if a museum like the Met had taken the first step and had encouraged other museums to be self-critical of their practices that perpetuate inequality, perhaps we could have slightly expedited this inherently slow process.

This generation may not witness significant advances in the redistribution of power in museums, which are known to be problematic institutions responding to sometimes conflicting interests. Museums are susceptible to controversy in the public eye and often have rigid structures legitimized by their donor and board systems. So, the changes will be gradual.

Nevertheless, without art that commits to exerting pressure on these monstrously powerful and seemingly immovable and perpetual structures like museums, without the brilliant ideas of groups like the Guerrilla Girls, the possibility of long-term change would not even exist. Therefore, those “intrepid and anonymous demographers of the art world status quo”[47] are aiming to “make feminism fashionable again”[48] after a period when the “feminist demonstrations of the 1970s had failed to move public opinion.”[49]

The relevance of the Guerrilla Girls is evident, and the Met poster remains current. Perhaps these times are calling for more racial and transfeminist diversity within the group, as new generations are recognizing intersections that second-wave feminism did not see. However, any generational shift concerns only the Guerrilla Girls, and they seek to divert public attention away from themselves and their group dynamics.

The question arises: do women have to wear gorilla masks to be heard? It seems like it has been a necessary and clever tactic for these artists. For the rest of us, the option is to continue fighting our personal and professional guerrillas (which may ultimately be the same, as the personal is political), such as myself, writing about this artwork because I think it is what I do best.

[1] Guerrilla Girls, “Posters, Stickers, Billboards, Videos, Actions: 1985-2023”, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.guerrillagirls.com/projects

[2] Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?,” accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/849438

[3] Anne Teresa Demo, “The Guerrilla Girls’ Comic Politics of Subversion.” Women’s Studies in Communication; Laramie 23, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 149.

[4] Eric Siegel, “Guerrillas Who Fight the Elitism in Art,” The Sun, September 30, 1990, 1C. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[5] Kerry O’Neill, “Striking at Sexism in the Art World”, The Christian Science Monitor, December 17, 1990, 10. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[6] Gertrude Stein et alias, “Guerrilla Girls and Guerrilla Girls BroadBand: Inside Story,” Art Journal, August 9, 2011.

[7] Roberta Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War’: Girls Sound the Discrimination Alarm in Art Circles,” Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1990, E7.

[8] O’Neill, “Striking”.

[9] Demo, “The Guerrilla Girls’ Comic,” 149.

[10] Stephanie L. Rhyner, “Satirical Warfare: Guerrilla Girls’ Performance and Activism from 1985-1995” (Master diss., University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015), 37.

[11] Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War,’” E7.

[12] O’Neill, “Striking”.

[13] The Guerrilla Girls use names of significant women in the art world to maintain their anonymity.

[14] Melena Ryzik, “The Guerrilla Girls, After 3 Decades, Still Rattling Art World Cages,” New York Times, August 15, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/09/arts/design/the-guerrilla-girls-after-3-decades-still-rattling-art-world-cages.html

[15] Guerrilla Girls, The Art of Behaving Badly (Chronicle Books LLC, 2020).

[16] Stein et alias, “Guerrilla Girls,” 91.

[17] Public Art Fund, “Guerrilla Girls: First They Want To Take Away A Woman’s Right To Choose… Now They’re Censoring Art,” accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.publicartfund.org/exhibitions/view/first-they-want-to-take-away-a-womans-right-to-choose-now-theyre-censoring-art/

[18] Gallery 98, “Public Art Fund, Guerrilla Girls, Billboard Project Card, 1991,” accessed November 30, 2023, https://gallery98.org/2017/guerrilla-girls-billboard-1991/

[19] Joan Smith, “Going Ape: Women Artists Go Underground to Fight Sexism in the Art World,” The San Francisco Examiner, February 25, 1990: 276.

[20] Says an anonymous untitled note in The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 3, 1989, 51.

[21] Stein et alias, “Guerrilla Girls,” 91.

[22] Guerrilla Girls, “Do Women Still Have To Be Naked To Get Into The Met. Museum?,” accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.guerrillagirls.com/naked-through-the-ages

[23] Paul Geitner, “Women Artists Fighting Guerrilla War: Masked Marvels Battle Sexism in the Art World,” Austin American Statesman, January 20, 1990, G5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[24] Says an anonymous untitled note in The Tennessean, February 4, 1990, 62.

[25] O’Neill, “Striking.”

[26] Siegel, “Guerrillas Who Fight,” 1C.

[27] O’Neill, “Striking.”

[28] O’Neill, “Striking.”

[29] Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War,’” E7.

[30] Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War,’” E7.

[31] O’Neill, “Striking.”

[32] O’Neill, “Striking.”

[33] O’Neill, “Striking.”

[34] Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War,’” E7.

[35] Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War,’” E7.

[36] Guerrilla Girls, “Do Women.”

[37] Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Do Women.”

[38] Artsy, “Guerrilla Girls: Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into The Met. Museum?,” accessed November, 30, 2023.

[39] Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War,’” E7.

[40] O’Neill, “Striking.”

[41] Gorilla Warfare in the Art World: Masked ‘Girls’ Fight Bias. The Washington Post, January 18, 1990, B10a. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[42] Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War,’” E7.

[43] Many examples are displayed on Guerrilla Girls, “Posters.”

[44] Geitner, “Women Artists,” G5.

[45] “Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, Inclusion.”

[46] Linda Nochlin, Why have there been no great women artists?, (London: Thames and Hudson, 2021).

[47] Roberta Smith, “Galleries Paint a Brighter Picture for Women: Is it Fashion or Progress?,” New York Times, April 14, 1989, C1, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[48] Smith, “Guerrilla ‘War,’” E7.

[49] Stein et alias, “Guerrilla Girls,” 91.

También te puede interesar

60 Artistas Participan en “frestas -trienal de Artes”, en Brasil

Entre el 12 de agosto y el 3 de diciembre de 2017, el Sesc de Sorocaba, en São Paulo, presenta la 2ª edición de Frestas - Trienal de Artes, un evento en el que...