OPEN WOUND. THE MOURNING OF HERNÁN PARADA

When art researcher Alejandro de la Fuente approached Chilean artist Hernán Parada to exhibit at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MAC) the entire constellation of materials that orbit around his Obrabierta -an ongoing work initiated in 1978-, he had no doubt. “It seemed like a confirmation to me,” says Parada. “The time had come to do something with the archive I had kept for years.” The story began on July 30, 1974, when agents of the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship kidnapped his older brother, then-university student Alejandro Parada, while he was sleeping in his house in Cerrillos. Since then, Hernán – who in 1972 enrolled the Universidad de Chile to study visual arts – felt the desire “to make art, make his brother appear and go out into the street.”

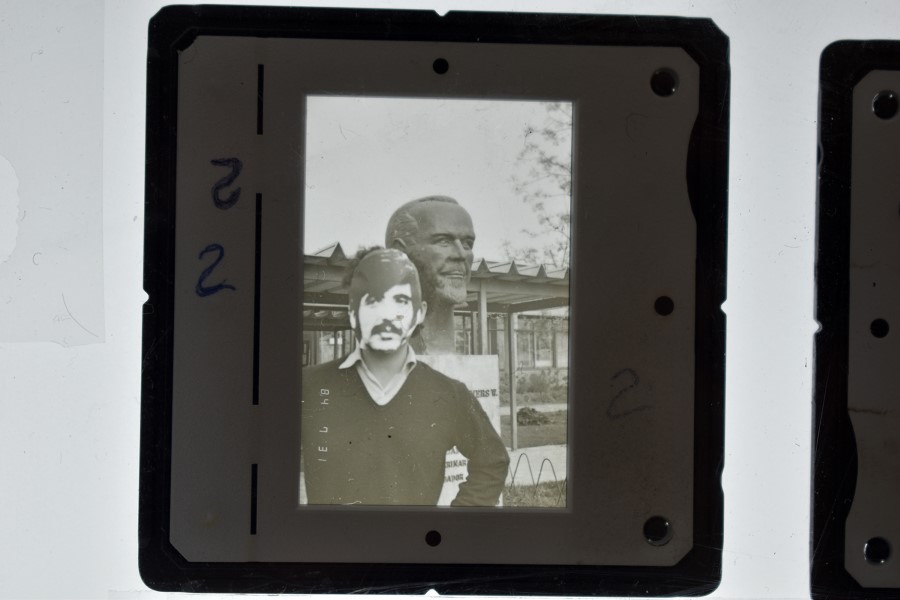

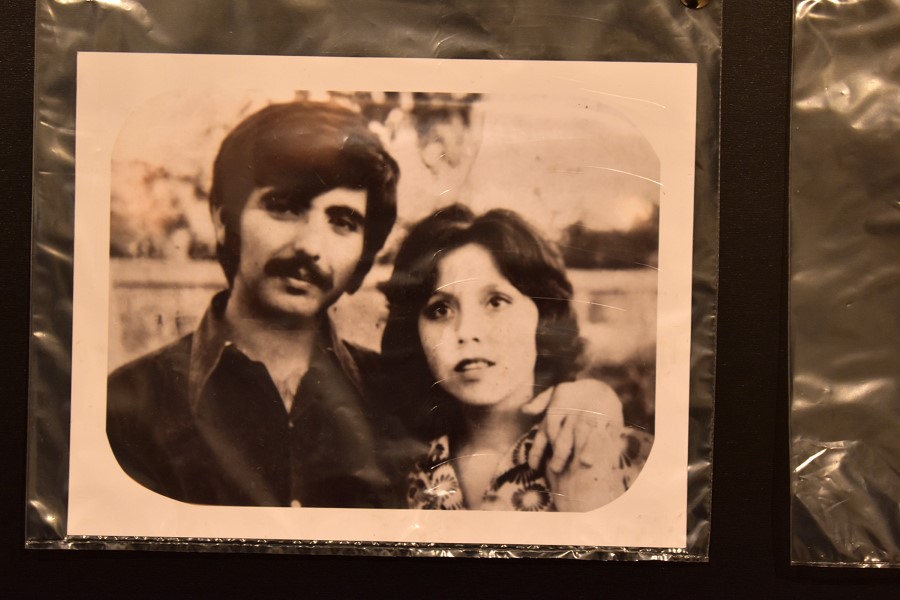

The initial idea was to carry a photo of him with Alejandro and take it to iconic places in the city. There were several recent family pictures of his brother. But Hernán says that he was incredibly moved by a frontal, half-length shot, in which he appeared next to his partner, taken shortly before his disappearance. “That photograph was published in Vicaría de la Solidaridad magazine. I fell in love with my brother’s expression and, besides that, the texture of the print allowed it to be enlarged without distorting it,” says Hernán. With that image, printed on a 46 x 60 cm photo paper, he headed to Plaza Italia -nowadays Plaza Dignidad-, and to the Palacio de la Moneda. He was accompanied by the artist Elías Adasme, and clandestinely, he photographed himself in front of those places holding the photo of his brother. It was late 1979.

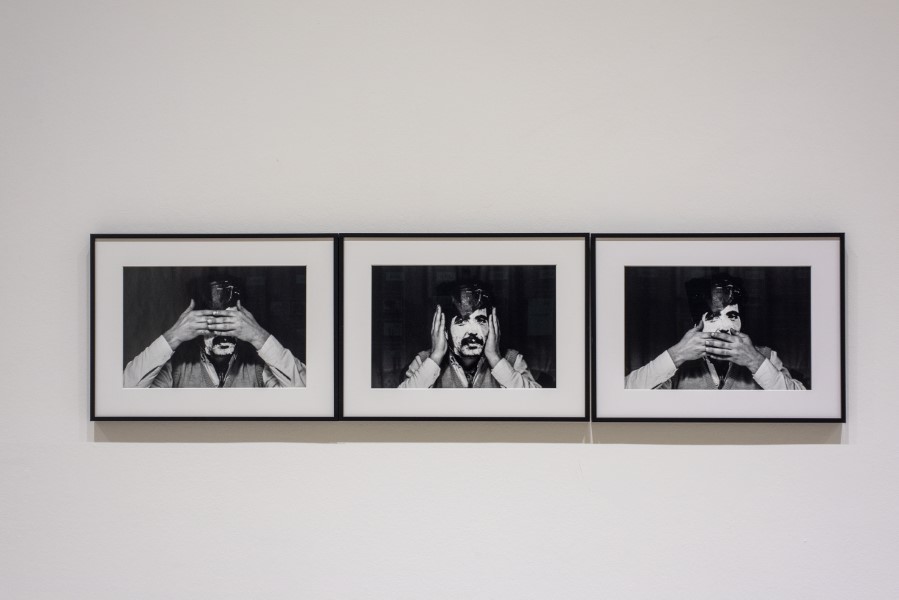

Hernán continued to perform the same action for several weeks but, at the beginning of the eighties, he gave a spin by making a mask of his brother’s face from that same portrait. He drilled into it two small holes at eye level through which he could see, but still he needed some guidance. Along with artist Víctor Hugo Codocedo, he went to the Palacio Tribunales de Justicia to carry out a photo-performance denouncing that justice was acting as an accomplice in Alejandro’s disappearance by rejecting the appeals for protection presented by various civil organizations. “They deny and make invisible the cases of violations of human rights,” says Hernán.

In that occasion, Víctor Hugo Codocedo took pictures of Hernán wearing the mask of his brother Alejandro inside the palace. Parada repeated the action in front of the Biblioteca Nacional, Escuela de Veterinaria, and Plaza de Armas. If someone approached him, he would say: “Hello, I’m Alejandro Parada; my brother Hernán lent me his body to come to talk to you. I want to know if you can give me some information to find out where I am because, right now, I am missing”.

The action continued in 1985 with Hernán walking around the city, wearing his brother’s mask outside Estación Central subway’s station, and around Patio 19 at the Cementerio General, just in front of the anonymous disappeared detainees’ mass grave. Luz Donoso took that photo series in sessions that the artist remembers as “very precarious and silent.”

“Bring in flowers to the N.N. It is something that my brother would have done”, says Hernán today. And the truth is that he knew what Alejandro was like better than anyone. They were very close during their childhood. In their parents’ apartment, on Matta and Viel Avenues, they both shared a room and a cabin bed. Alejandro slept up and Hernán down. Although Hernán asserts that they did not physically resemble each other (his missing brother had short, straight hair, while he had long, curly hair), they both had mustaches and blue eyes. “I was more of a crybaby than he was, and, the last time I wore his mask for my performances, it covered the fact that I was crying.”

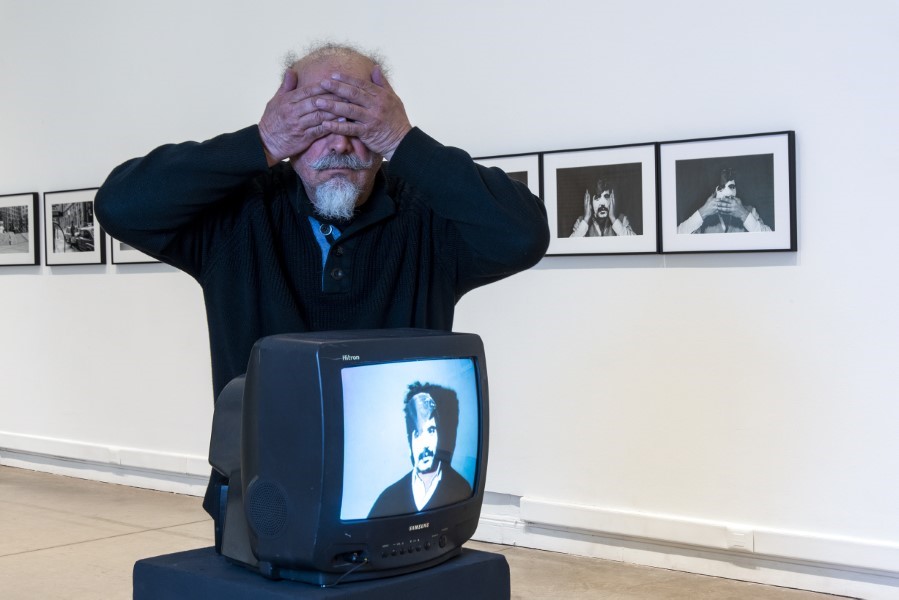

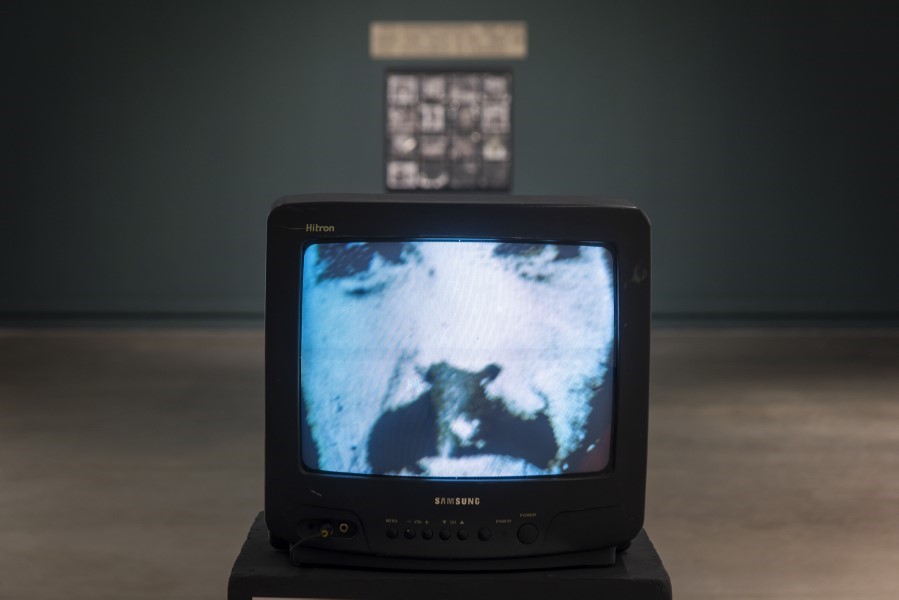

In Obrabierta: El Tiempo, La Vida, La Información, the exhibition curated by Alejandro de la Fuente and recently opened at MAC Santiago, the artist’s archive is displayed, including original pieces that until today had not been digitized or exhibited. Alongside the archive are records of political actions by the Asociación de Detenidos Desaparecidos and photographs that Parada captured while working with the group. The exhibition, in its entirety, exposes the conceptual richness of Parada’s work and his exquisite visual craftsmanship, while at the same time being tremendously emotional.

Seeing the exhibition, Hernán assures he is moved. He had never seen the material gathered. He further says the image he has of his brother has not changed over time. Within his family they continue to remember him constantly, and in light of events, it seems that Hernán Parada’s work is not only open but is also a way of mourning. “Obrabierta is not closed until Alejandro reappears,” he says firmly.

Even today, Hernán continues to lend a body to his brother. Every time he donates blood, for instance, he does it twice: blood is drawn once in his name, and a second time in the name of his brother. 17,455 days have passed since Alejandro Parada disappeared and 44 years since Hernán began working in Obrabierta. No one has ever asked the artist what his brother would think of the work he has kept open in his memory. To answer this, Hernán lends his voice to ‘Cano’, as they affectionately called Alejandro back then: “It seems that you loved me because you have spent a lot of time thinking about me. Thanks for that. Thanks for remembering».

OBRABIERTA: el tiempo, la vida, la información, de Hernán Parada, is on view until July 9th, 2022, at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MAC), Parque Forestal, Santiago, Chile

También te puede interesar

TECNOCHAMANISMO ROEDOR

En varios sentidos, Marco Arias fue el principal agente de la escena chilena de arte otaku que vivió su apogeo entre 2017 y 2019; escena que nació espontáneamente de la conjugación de algunas poéticas...

JUAN CÉSPEDES: MISTERIOS MISTERIOSOS DE LA LONTANANZA LEJANA (PRIMERA PARTE)

La tercera exposición individual del artista chileno en la galería Die Ecke (Santiago) incluye una serie de pinturas, cuyos procesos formales tienen relación directa con los recursos técnicos utilizados en el uso del aerógrafo,...

MÁXIMO CORVALÁN-PINCHEIRA: PADECE

Cuando Corvalán-Pincheira tomó conciencia del peligro ambiental que enfrenta la araucaria en el Sur de Chile, cambió su interés de una década por el ADN de pueblos desaparecidos en Chile, Estados Unidos, México y...