MARKING TIME: ART IN THE AGE OF MASS INCARCERATION

More than two million people are currently behind bars in the United States. Incarceration not only separates the imprisoned from their families and communities; it also exposes them to shocking levels of deprivation and abuse and subjects them to the arbitrary cruelties of the criminal justice system. Yet, as Professor of American Studies and Art History at Rutgers University Nicole Fleetwood reveals, US’s prisons are filled with art. Despite the isolation and degradation they experience, the incarcerated are driven to assert their humanity in the face of a system that dehumanizes them.

Fleetwood is the guest curator of Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, a survey and analysis of visual art and creative practices among incarcerated artists, as well as art that responds to mass incarceration exploring the work of artists within US prisons and the centrality of incarceration to contemporary art and culture. The exhibition is on view at PS1 MoMA until April 4, 2021.

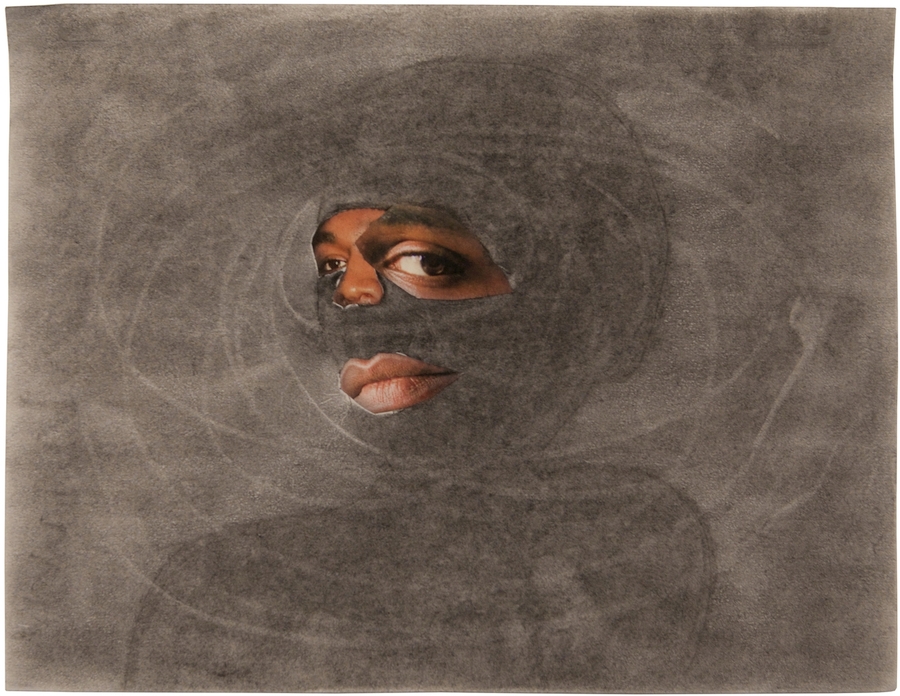

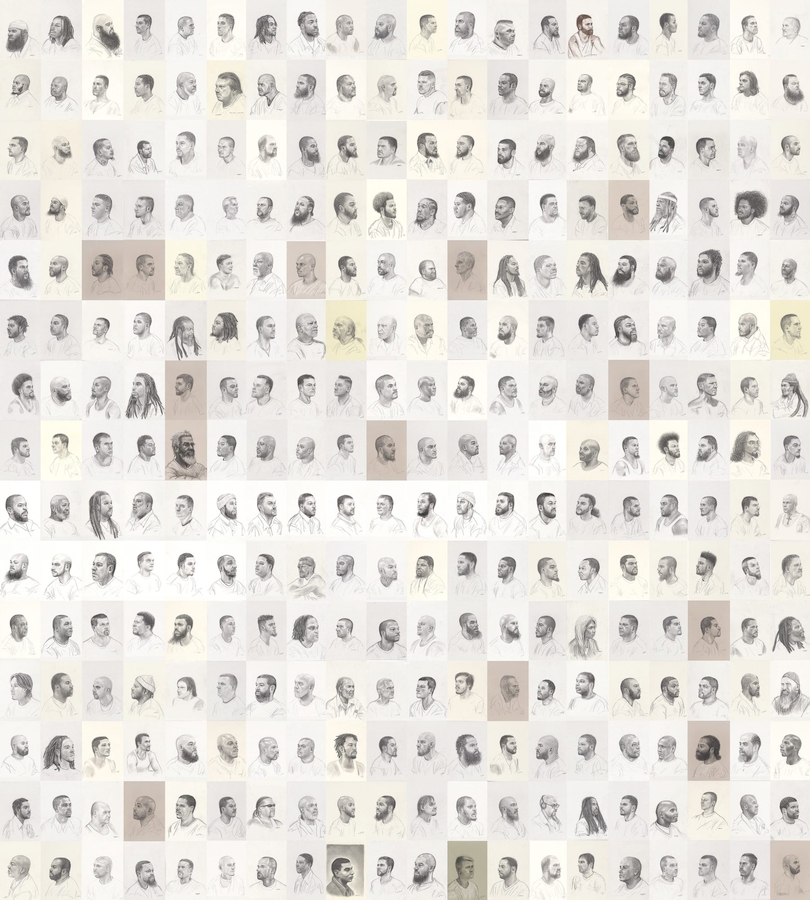

Featuring art made by people in prisons and work by non-incarcerated artists concerned with state repression, erasure, and imprisonment, the exhibition highlights more than 35 artists, including Tameca Cole, Russell Craig, Maria Gaspar, James “Yaya” Hough, Jesse Krimes, Mark Loughney, Gilberto Rivera, and Sable Elyse Smith. The presentation has been updated to reflect the growing COVID-19 crisis in US prisons, featuring new works by exhibition artists made in response to this ongoing emergency.

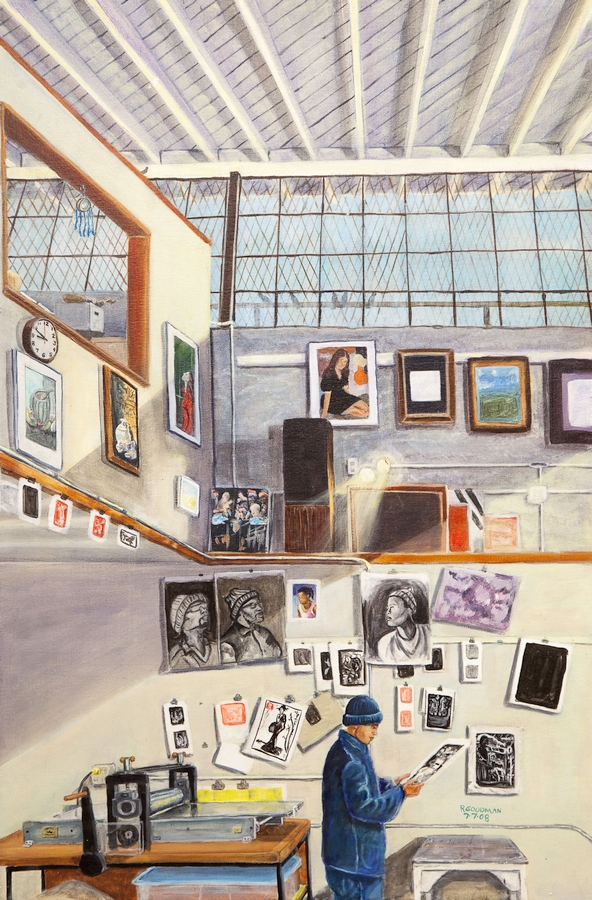

Based on interviews with currently and formerly incarcerated artists, prison visits, and the author’s own family experiences with the penal system, Marking Time shows how the imprisoned turn ordinary objects into elaborate works of art. Working with meager supplies and in the harshest conditions—including solitary confinement—these artists find ways to resist the brutality and depravity that prisons engender.

“I originally started working on Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration as a way to deal with the grief about so many of my relatives, neighbors, and childhood friends who were spending years, decades, or life sentences in prison. It was also an effort to connect with others who are separated from their loved ones by prisons, parole, policed streets, and other forms of institutional and quotidian violence,” Fleetwood explains in Creation in Confinement: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, an article published by The New York Review.

The impact of their art, Fleetwood observes, can be felt far beyond prison walls. Their bold works have opened new possibilities in US art.

“Marking Time is about both the centrality of prisons in contemporary art and culture and the robust world of art-making inside US prisons. I set out to engage the politics of this art-making in prisons, and, more expansively, art as politics in an era of extensive human caging and under other forms of carceral power. How has the colossal reach of the prison industrial complex shaped contemporary art institutions and art-making? And how does visual art help to reveal the depth of devastation caused by our nation’s punishment system?”, she adds.

Marking Time features works that bear witness to artists’ experimentation with and reimagining of the fundamentals of living—time, space, and physical matter—pushing the possibilities of these basic features of daily experience to create new aesthetic visions achieved through material and formal invention. The resulting work is often laborious, time-consuming, and immersive, as incarcerated artists manage penal time through their work and experiment with the material constraints that shape art-making in prison.

The exhibition also includes work made by non-incarcerated artists —both artists who were formerly incarcerated and those personally impacted by the US prison system. From various sites of freedom or unfreedom, these artists devise strategies for visualizing, mapping, and making physically present the impact and scale of life under carceral conditions, underscoring how prisons and the prison industrial complex have shaped contemporary culture.

Rowan Renee‘s No spirit for me (2019) is an installation composed of reproductions and re-creations of her father’s criminal case file from the Florida State Attorney who prosecuted him. The file included the official records used to condemn her father – court records, witness statements and police evidence photographs. Through these documents, she was able to track how the justice process failed in a case that the State hailed as an example of justice served.

Using lithography, weaving and metalwork, Renee re-presents over 1000 pages of these records as “hanging files” in a fictitious police evidence room. The repetitive motions of printing 1000 pages through an etching press, of tracing the shapes of redaction on the loom, of welding dozens of steel joints was a method to use her body –the site of violence– as a vehicle for justice.

As the movement to transform the country’s criminal justice system grows, art provides the imprisoned with a political voice. Their works testify to the economic and racial injustices that underpin American punishment and offer a new vision of freedom for the twenty-first century.

“As hundreds of thousands of people take to the streets demanding the defunding of police departments, the end of anti-Black racism, and justice for George Floyd, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Rayshard Brooks, it is important to remember that the seeds of the police and prison abolitionist movement were planted long ago, as far back as the struggle to end slavery. In recent decades, Black women have tended these seeds by developing the conceptual framework for the movement (think Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Mariame Kaba) and by performing the care labor of holding together communities that have been convulsed by mass incarceration”, says Fleetwood.

Marking Time reflects her decade-long commitment to the research, analysis, and archiving of the visual art and creative practices of incarcerated artists and art that responds to mass incarceration. The exhibition follows the release of Fleetwood’s new book, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Harvard University Press, 2020) [1], a thoroughly researched and heartbreakingly personal look at prison art and the broader visual culture of incarceration, and the way art becomes a mode of relationality among prisoners who use it to combat the imposed isolation of imprisonment.

Rather than analyzing prison art as “outsider art” or as a form of therapy, Fleetwood uses the term “carceral aesthetics” to describe how penal space, time, and matter shape the production of the art she examines. Other studies have focused on art programs and workshops based on models of art therapy, which grow out of the disciplines of psychology, education, and criminology and which promote exploring creative outlets as forms of healing and rehabilitating people.

“My main concern about a rehabilitative framework is that in its primary focus on changing the individual, it does not offer an analysis or critique of how the carceral state relies on producing criminal subjects. My engagement with art is through an abolitionist perspective, and while I do not write about prison art as necessarily therapeutic or rehabilitative, I do acknowledge and respect that many incarcerated artists use and understand art-making as part of their healing and coping inside prisons.”

Incarcerated artists create under conditions of extreme duress. Their supplies are limited to what they can purchase through the commissary or access through arts programs (which, if available at all, are usually restricted to prisoners with no disciplinary records). Certain paint colors are banned (due to their chemical composition) and the kinds of items prisoners can possess are strictly regulated.

Prisoners are always being watched. The content of the work they produce, what they can say to outside collaborators, and how they circulate their work are censored or mediated by prison administrators. And yet they still create art—often compulsively, sometimes using contraband materials or repurposed trash. Art can also be a means of survival for prisoners who trade it for food, services, or commissary items.

“One of the challenges of writing about this has been that many of the artists, whether currently or formerly incarcerated, do not have possession of their art, nor any documentation of their work, nor knowledge of how and where their art has circulated. For reasons that have to do with the inequality and exploitation that incarcerated people suffer, art made in prison may be sent to relatives, traded with fellow prisoners, sold or ‘gifted’ to prison staff, donated to nonprofit organizations, and sometimes made for private clients. There are people I interviewed who described their work and practices to me but had nothing to show.”

Art made by people in prison can even be lucrative for some institutions, and art workshops and education can function as ways of managing people held captive so that they do not challenge prison authority. At Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola, prison art is sold at the biannual rodeo show, bringing in significant profit to the institution, with a percentage for the incarcerated people, who can use it toward commissary or send it home to relatives.

Over the last 40 years, incarceration has grown into an $80 billion industry. One that depends on the human caging of 2.3 million people to extract wealth and resources from the economically-distressed, and disproportionately black and brown communities unjustly targeted by our criminal legal system. Companies like Securus and Union Supply charge spouses $3.95 to listen to a voicemail from their partners and mothers $4.15 to deposit $10 on the commissary accounts of their children.

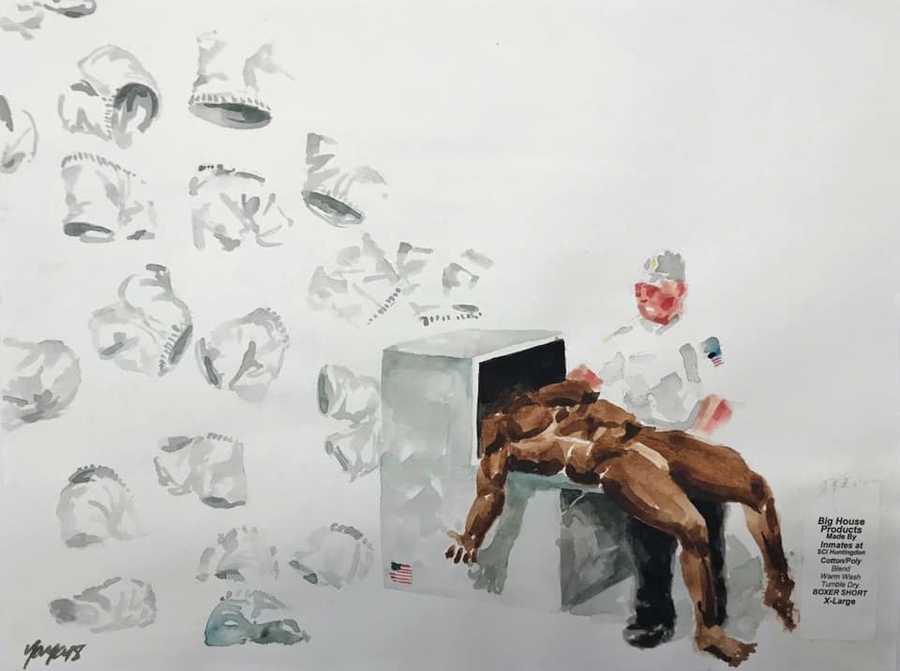

Incarcerated people know best that profits in the prison industry are directly linked to suffering. Often, however, words fall short in conveying the harms that commercialization inflicts. In James “Yaya” Hough’s How Big House Products Makes Boxer Shorts, for instance, an African American prisoner’s body is being used, or processed, by Pennsylvania Correctional Industries to make Big House products, like boxer shorts, for slave wages. These products are sold back to prisoners. A pack of six Big House boxer shorts costs $3.09 in commissary.

Sentenced to life in prison without parole at seventeen years old, James «Yaya» Hough spent 27 years in a cell in Pennsylvania before he was released in August 2019. While imprisoned, he created a huge body of work exploring recurring themes of isolation, race, interpersonal violence, resistance of authoritarian systems, and the relationship between sex and violence in the US. By making and forming creative communities inside prison (including a deep friendship with fellow Marking Time artists Russell Craig and Jesse Krimes), Hough fought the punitive isolation that is imposed incarcerated people.

In the weeks following the murder of George Floyd, Hough took over PS1 Instagram account to reflect on the crisis of white supremacy in his hometown of Philadelphia. «As a Black man in this city, I am constantly confronted with an existential dilemma: am I a citizen, or their potential problem?»

Alongside the exhibition, a series of public programs, education initiatives, and ongoing projects at MoMA PS1 will explore the social and cultural impact of mass incarceration.

[1] So far, the book has won the following recognitions: National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist; Smithsonian Book of the Year; New York Review of Books Best of 2020; New York Times Best Art Book of the Year; The Art Newspaper Book of the Year.

También te puede interesar

BUILDING RADICAL SOIL

"Building Radical Soil", exposición organizada por The Latinx Project de la Universidad de Nueva York (NYU) y curada por Sofía Shaula Reeser-del Rio, reúne los trabajos de un grupo de artistas latinxs que analizan...