THE BOTANICAL MIND. ART, MYSTICISM AND THE COSMIC TREE

Humanity’s place in the natural order is under scrutiny as never before, held in a precarious balance between visible and invisible forces: from the microscopic threat of a virus to the monumental power of climate change.

Drawing on indigenous traditions from the Amazon rainforest; alternative perspectives on Western scientific rationalism; and new thinking around plant intelligence, philosophy and cultural theory, the online exhibition The Botanical Mind investigates the significance of the plant kingdom to human life, consciousness and spirituality across cultures and through time. It positions the plant as both a universal symbol found in almost every civilisation and religion across the globe, and the most fundamental but misunderstood form of life on our planet.

This new online project has been developed in response to the COVID-19 crisis and the closure of the Camden Art Centre (London) due to the pandemic. Curated by Gina Buenfeld and Martin Clark, The Botanical Mind: Art, Mysticism and The Cosmic Tree was originally conceived as a trans-generational group exhibition, bringing together surrealist, modernist and contemporary works alongside historical and ethnographic artefacts, textiles and manuscripts spanning more than 500 years.

Including new digital commissions; a focus on the Yawanawa people of Amazonian Brazil, who were to travel to London to take part in the exhibition but are now self-isolating in their village; and a new podcast series drawing on some of the leading voices in the fields of science, anthropology, music, art and philosophy, the project forms an expanding archive exploring ideas of plant sentience, indigenous cosmologies, radical botany, Gaia theory, quantum biology, and the influence of psychoactive plant medicines on various cultures and counter-cultures across the globe.

During this period of enforced stillness, our behaviour might be seen to resonate with plants: like them we are now fixed in one place, subject to new rhythms of time, contemplation, personal growth and transformation. Millions of years ago plants chose to forego mobility in favour of a life rooted in place, embedded in a particular context or environment. The life of a plant is one of constant, sensitive response to its environment—a process of growth, problem-solving, nourishment and transformation, played out at speeds and scales very different to our own. In this moment of global crisis and change there has perhaps never been a better moment to reflect on and learn from them.

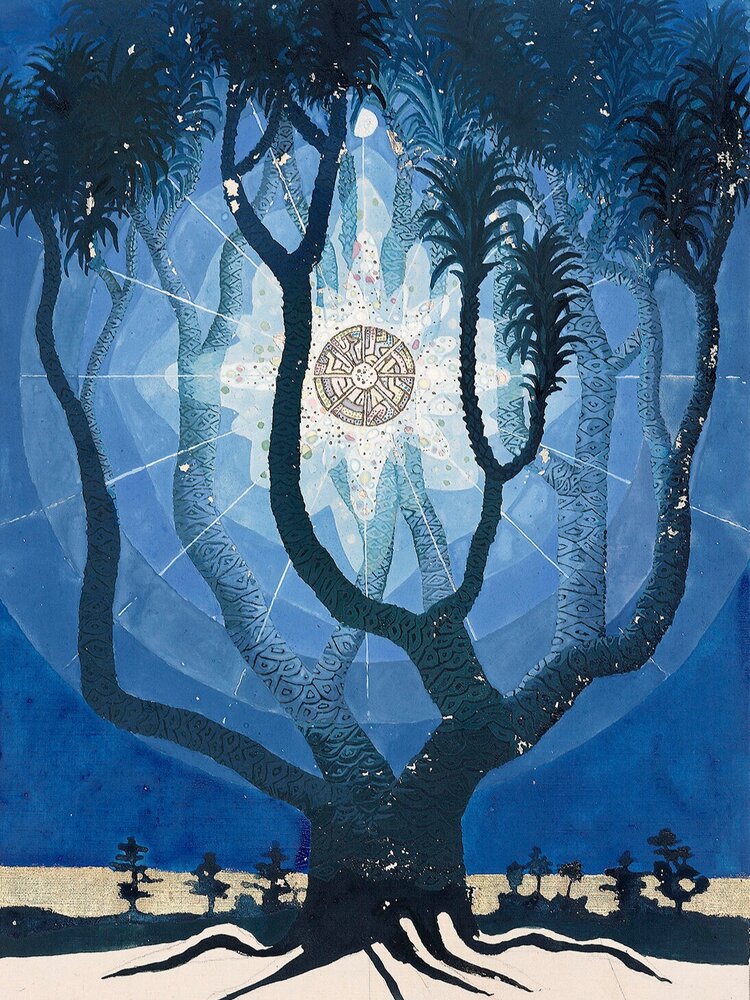

The Cosmic Tree

The Cosmic Tree is a universal archetype that appears in the symbolism and mythologies of countless civilisations. It represents the Axis Mundi, or World Axis, that connects every aspect of the universe. The motif of a sacred tree is often associated with the figure of a serpent – an emblem of the shamanic experience, ascending from the shadows to the spiritual plane.

The great Twentieth century psychoanalyst Carl Jung developed a deep understanding of the archetypes of the collective unconscious and how they emerge as symbolic images. He created an extraordinary manuscript – the Liber Novus – now commonly known as The Red Book, filled with symbolic images he discovered in the depths of his own mind. The tree was a recurring motif, pictured as both supporting and connecting every aspect of the cosmos. Planted in the earth its roots reach down through the terrestrial realm toward darkness and the shadow realm, whilst its branches stretch up through the celestial, toward the star-filled heavens.

Artist Andrea Büttner reveals the now-overgrown planting-beds and greenhouses in a former Nazi concentration camp. Last year, she made a video, Karmel Dachau, about a Carmelite convent that was founded in 1964 adjacent to the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial. “I’ve known this convent since my childhood. Next to the concentration camp memorial, former greenhouse structures and the concrete borders of plant beds still exist. They were part of the plantation at the Dachau concentration camp, where the prisoners had to work and were killed by labor. One of the purposes of the Nazi’s plantation was cultivate German drugs, German herbs, and to do research in biodynamic gardening.”

Sacred Geometry

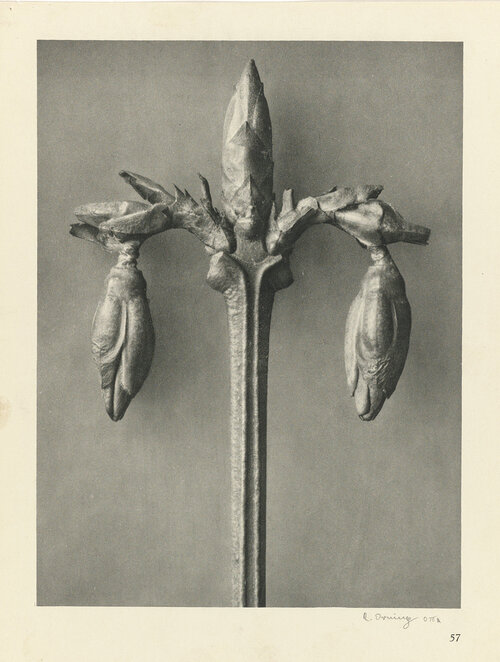

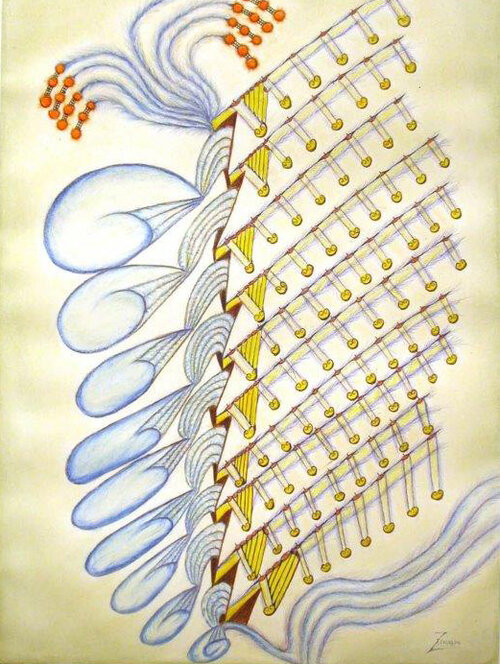

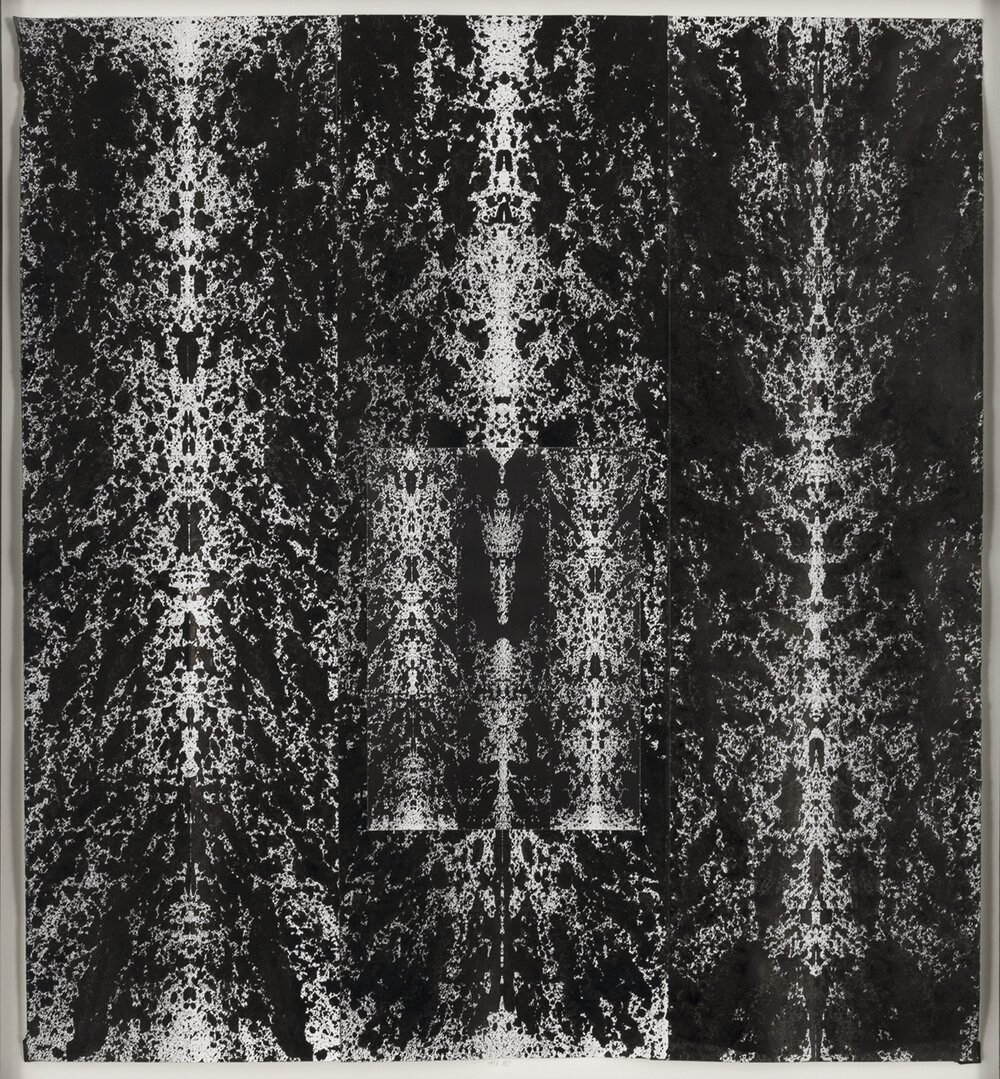

Echoing the fractal and spiral geometries inherent in plant-forms and flowers – as well as the psychoactive visions induced by (entheogenic) mind-manifesting plant medicines – certain patterns or designs emerge again and again in art and science, appearing and reappearing across cultures and through time. Blueprints for the natural world, they seem to connect the macro- to the micro-cosmos, revealing an encoded intelligence. These ‘sacred’ geometries can be seen in the arrangement of Camelia and Dahlia petals, the seeds in a sunflower head or the fractals of Romanesco broccoli. They recur throughout nature in the animal, mineral and vegetal kingdoms – the curve of a conch shell resembles the unfurling of a fern, or the spiral of a lizard’s tail. The flower-like figure of the mandala, common to Indian, Japanese, Persian, Mesoamerican and European religions, is one of the oldest spiritual symbols and another example of these sacred geometries. As too, is the proliferation of pattern and repetition found across Islamic, Nordic and Neolithic art. As Theophrastus wrote in the 2nd Century BC: ‘Repetition is the essence of the plant’ – a life of unceasing nourishment, growth, replication, and a complex and constant extrapolation of forms.

Indigenous Cosmologies

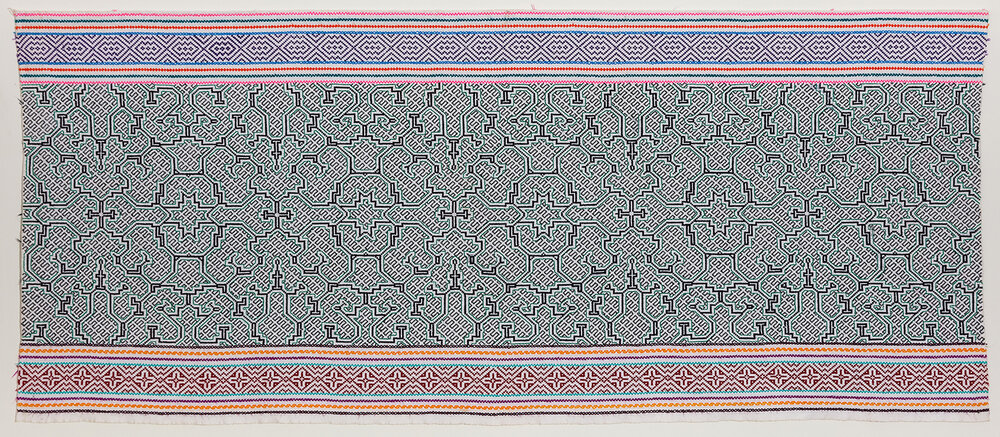

In the Amazon rainforest, the patterns found in nature are the basis of sacred geometries that indigenous people paint onto their skin and ceramics, or weave and embroider as textiles or bead-work. They call these patterns ‘kené (sacred designs) and some say that these geometries once connected the universe in a continuous tissue -a primordial reality in which the planes of existence (material, immaterial, visible, invisible) were once unified and whole.

The Yawanawá people are settled in villages along the banks of River Gregorio, in the Brazilian rainforest -guardians of 200,000 hectares of biodiverse virgin rainforest. They survived violent contact with western society and after nearly a century of domination they have reclaimed their land and freedom, their ancestral culture and spirituality. They live in harmony with the natural cycles of nature, nourishing a profound connection with the healing plants of the Amazon.

In collaboration with Delfina Muñoz de Toro, an indigenist, visual artist and musician from Argentina, and artists from the Yawanawá family, The Botanical Mind presents a new project based on their kené and music. Their designs and music are central to their cosmology -their aesthetic vision involving plants, animals, and beings from the spirit world.

The Covid-19 pandemic poses a particular threat to indigenous communities who are vulnerable to infections and diseases from outside their territories. During the European colonisation of the Amazon, many ethnic groups were decimated by diseases that they had no immunity to. The Yawanawá, like many other indigenous communities, are now in self-isolation in their sacred village.

In 2014, independent filmmakers and sound-explorers Priscilla Telmon & Vincent Moon spent time with the Yawanawá family, recording and filming their daily life in the rainforest. This footage is part of an archive of the diverse spiritual traditions in Brazil and their interwoven roots –Híbridos [Hybrids] – amassed over a four-year period.

Their films are all available on their open-source, creative commons, platform and span the traditional ceremonies and plant-based healing techniques of indigenous peoples of the Amazon, as well as the syncretic lines of Umbanda –an Afro-Brazilian religion– and Santo Daime, which incorporates folk Catholicism, African Animism, and indigenous shamanism from South America, in particular the use of a sacred plant medicine known as Ayahuasca. Telmon and Moon’s ethnographic experimental films and music recordings explore transcendent states with image and sound -filming sacred music, religious and shamanic rituals and drawing from the wisdom traditions and teachings they receive from spiritual elders and shamans around the world. They are compelled by a shared knowledge that everything, visible and invisible, is vibrating energy, the foundation of ancient science and healing through music.

Indigenous Amazonian people have a wealth of knowledge about their plant allies gained not through scientific experiment but in communion with music and the senses. They make allegiances with plants they consider to be sacred ancestors, emissaries of spiritual wisdom, plants that guide them and reveal their healing properties and preparations as musical transmissions -icaros or healing songs. In the Shipibo-Conibo lineage, an ethnic group indigenous to the Amazonian lowlands of Peru, these songs can have both visual and aural form, distinctive vocal and percussive music that is whispered, whistled and sung to stimulate contact with a subtle dimension that’s interlaced with intricate abstract geometries. For these communities, both music and visual abstraction are central to their deeply entwined relationship with the rainforest.

For the Huni Kuin people from the Amazon rainforest in Brazil, their designs are passed through ancestral lines signifying indigenous identity and spirituality. They sing music while they weave them into textiles -specific songs that are related to the designs they are making. They learn to weave from an early age and have a sense of transformation through the process which for them, is intimately related to The Great Spirit.

In the Twentieth Century many European artists and thinkers were inspired by indigenous cultures in the Americas, including Yves Laloy and Wolfgang Paalen. Josef and Anni Albers spent periods of time in Mexico and Peru where their work was influenced by pre-Colombian aesthetics, the ancient stone carvings at Mitla, and the traditional textiles of Andean weavers.

Astrological Botany

The intrinsic connection between geometry, music and the earthly and astral realms has been contemplated by European philosophers and artists since antiquity. But it would resurface in the 20th century in works by a number of outsider, surrealist and modernist artists including Anna Zemankova, Adolf Wölfli, Hilma Af Klint, Ithell Colqhoun, Eileen Agar, and Anni and Josef Albers.

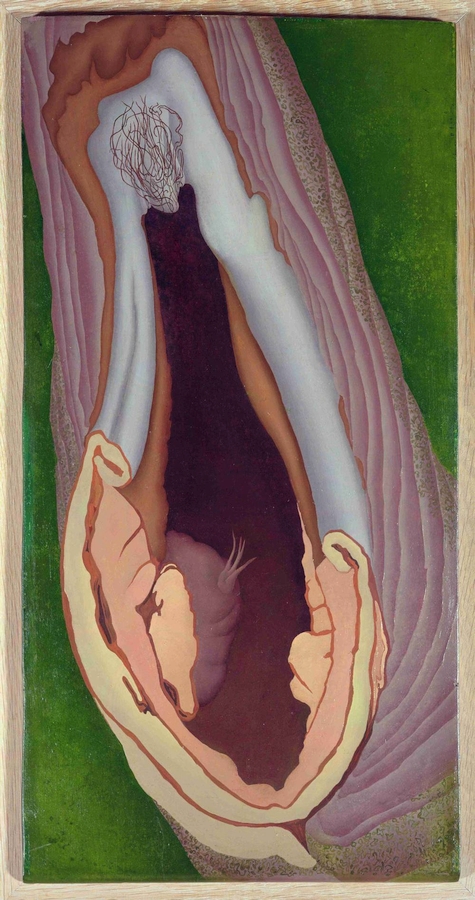

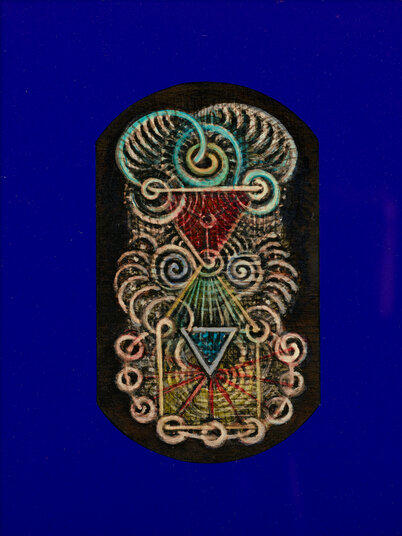

Ithell Colquhoun (b. 1906-d. 1988) was a British-Indian artist and occultist. She studied at the Slade in the late 1920s and was later a member of the British Surrealist Group. She was expelled soon after, her work and ideas apparently too esoteric, even for them. As well as her work as an artist, she wrote a number of books and articles on magic, divination, landscape, and myth, as well as stories and poems. Colquhoun was a practicing occultist, interested in various systems of magical thought, hermeticism and alchemy. She created a tarot from shapes and forms automatically produced through poured enamel paints, as well as making paintings and drawings based on various automatic, or ‘mantic’ techniques. These works sought a kind of equivalence with the patterns and forms of nature and were, for her, aids to divination, enlightenment and knowledge.

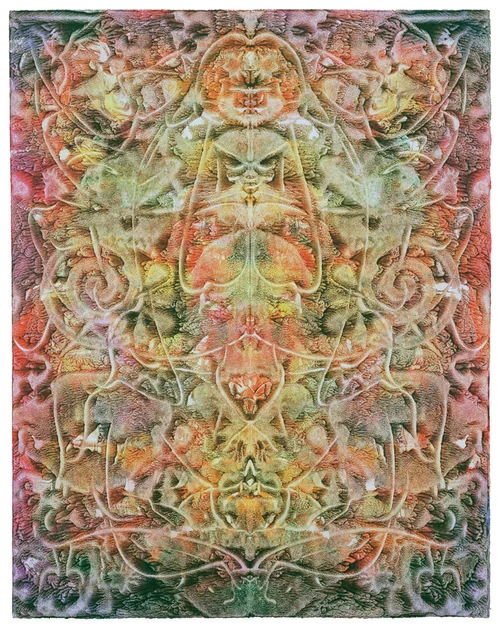

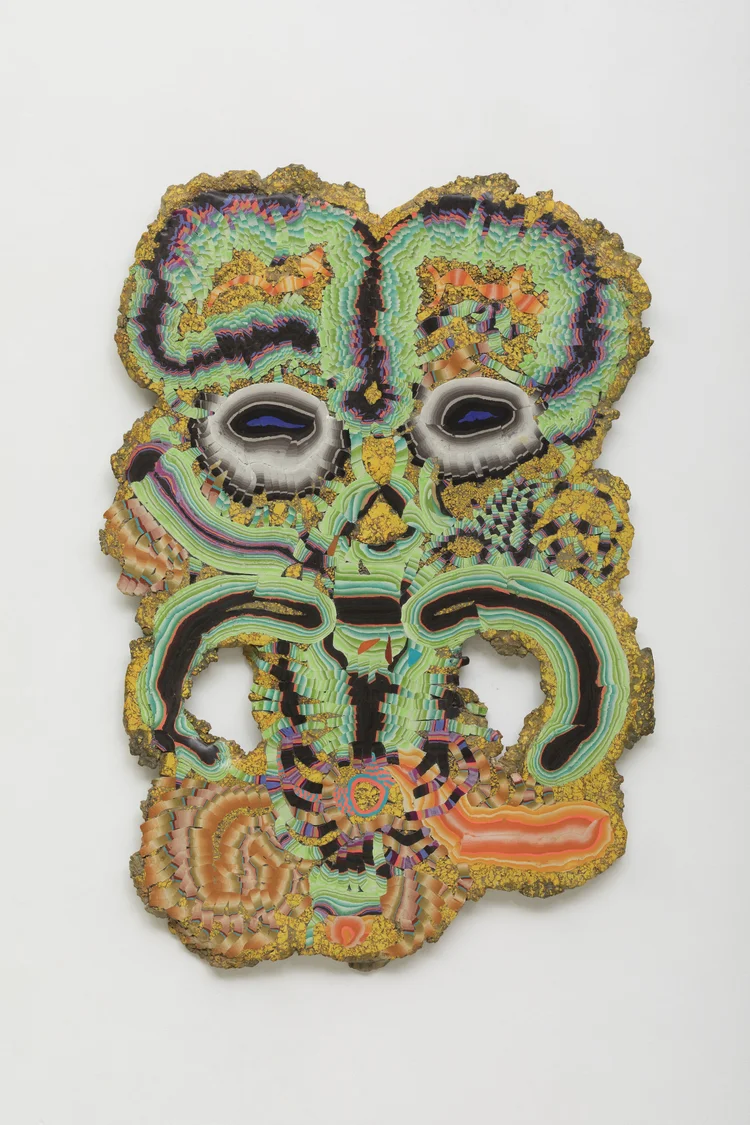

Kerstin Brätsch’s practice has involved collaborations with other artists, astrologers, psychics and artisans working with traditional stained glass and paper marbling techniques. Her distinctive, highly saturated and abstract images resemble patterns found in nature –geodes or other stone formations, or the markings of plants and animals– and also read like ciphers, a kind of language. She works with processes that are like alchemical rituals, combining pigments and liquids with other materials in precise measures according to traditional, event ancient, methods and surrendering to the intelligence of the materials in themselves – the way they behave.

23 1/16 x 21 7/16 in. (58.6 x 54.5 cm). Photo: Steven Probert © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

As Within, So Without

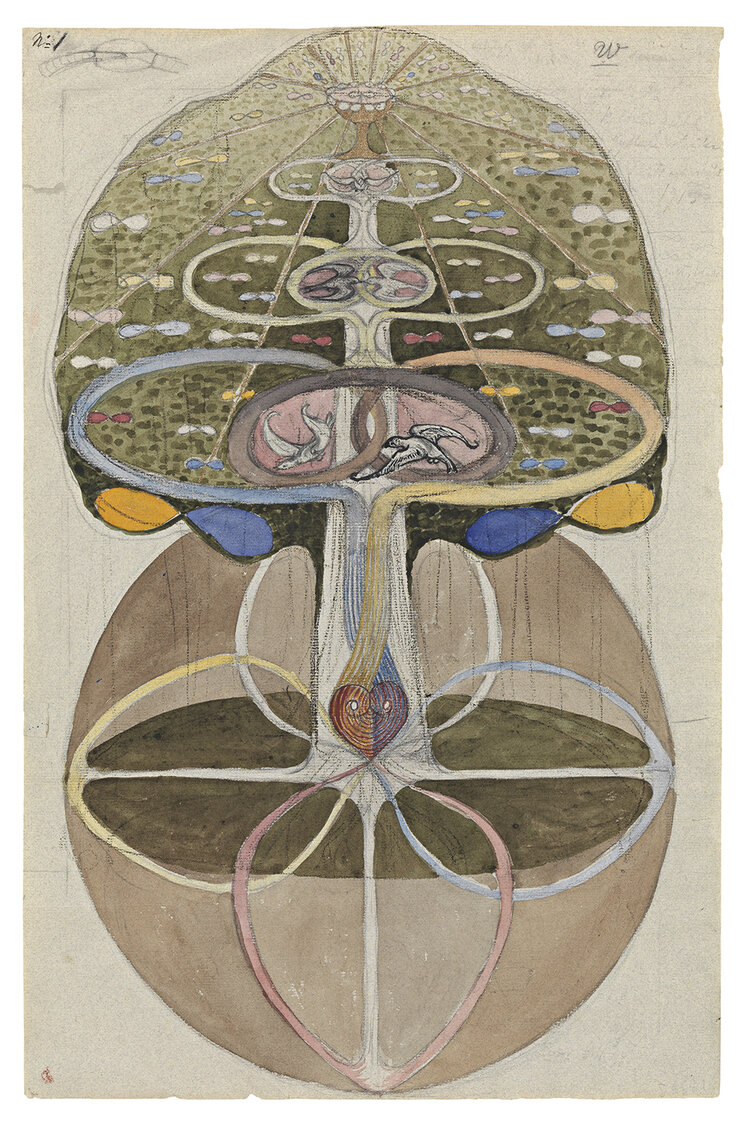

In Carl Jung’s concept of the archetypes, he perceived continuities between the forms of physical as well as psychic reality, essential patterns – regularities of form and structure – that appear in nature and arise naturally in the mind. The many mandalas that appear in his Liber Novus, or Red Book, were created with a method he called Active Imagination – an attempt to ‘form in matter’ his innermost thoughts and the structure of his psyche.

The mandala is one of the oldest spiritual symbols and an image which attempts to both represent the universe schematically – with the individual subject occupying the central position – whilst also operating as an active meditation device, a gateway enabling transformative states of consciousness. They are common to various traditions of eastern and western mysticism, but they have also been created by a number of contemporary and modern artists.

The popularised fractal or spiral geometries associated with the art and images of psychedelia, appear not only in the morphology of plants but in the visions induced by mind-manifesting plant medicines, like Psilocybin found naturally in certain mushrooms, Mescaline arising in the Peyote cactus or Dimethyltryptamine, a substance secreted naturally in the brain, and activated when drinking Ayahuasca. The mystical experiences invoked by psychoactive plants, as well as encounters with Eastern mysticism, became central to the counter-cultural revolution of the 1960s, exemplified in art, music and literature by figures like Bruce Conner, William Burroughs, Aldous Huxley and Brion Gysin.

Scholars have also speculated on the role of entheogenic plants in the evolution of consciousness and language, as well as the development of global religions, including that the mystical substance Soma in the ancient Indian Vedas was a psychoactive mushroom, and that the ritualistic use of psychedelic plants played a part in the development of Christianity.

Bruce Conner (1933-2008), well known for his landmark experimental films, was motivated by mysticism, spirituality and psychedelia. His visionary works were often filled with dark subject matter, symbolic and religious imagery. One of Conner’s first departures from the found material that constituted his earlier works is Looking for Mushrooms, a visionary travelogue including footage of journeys he and his wife Jean made in Mexico, as well as scenes of their life in San Francisco. Between 1961 – 62 while he and Jean were living in Mexico City, they ventured into the rural landscapes to look for psychedelic mushrooms, on at least one occasion accompanied by Timothy Leary who appears on camera. The original version was shown as a loop, with a soundtrack by The Beatles. Conner revisited it in 1996, repeating each frame five times, stretching the footage out to fourteen-and-a-half minutes and accompanying it with a soundtrack composed and performed by experimental musician Terry Riley. The, at-times dark, subject matter combined with rapid rhythm, multiple-exposure sequences and strobe effects, evokes an atmosphere of meditation or perhaps even a psychedelic experience, in which subliminal images are allowed space to arise within the mind.

Jordan Belson (1926 – 2011) made paintings from a young age and later became known as one of the most important artists in 20th century avant-garde cinema and visual music. He was interested in expansive states of consciousness, devoting himself to a meditation practice and experimenting with hallucinogens. His films and paintings convey the inner images of his mind’s eye, of altered psychic states. He sought universal truths by voyaging inwardly, through meditation, to discover primary forms – circles, spheres, squares, pentagrams, hexagons – that also appear in sacred art, in Tibetan mandalas and tantric paintings.

Belson was a mystic who combined the spiritual with the scientific, with geometry and physics. His paintings and films are filled with dynamic and abstract forms that could equally emerge in the nebulous forms of deep space phenomena, the celestial, as well as in the sub-atomic realm or the immaterial expanses of the mind.

Vegetal Ontology

Plant sentience is often dismissed as its characteristics cannot easily be overlaid on the signs of consciousness expressed in human, or animal, subjects. A philosophical consideration of vegetal life requires an expanded appreciation for modes of being peculiar to plants, attending to them on their own terms as centres of intelligence that exert behaviour within scales of time and movement that differ vastly from our own. If the animal is bounded by a body that moves, the plant is instead defined in ‘being-sessile’; rooted in one place and subject to change and growth in a complex and highly sophisticated relationship with its environment.

We now know that plants can learn from experience and environmental stimuli; that they can interact and communicate, not just with other plants but with other animals and insects in highly manipulative ways; and their sensitive, rhizomatic root structure and decentred, collective intelligence provides a far more modern way of thinking about social and environmental relations. To be sessile, embedded in a milieu, is to express life-force on a molecular-cellular level. Plants do not possess a neurological centre but, like art perhaps, they are defined by a state of ceaseless unfolding, a material knowledge or thinking without thinking, and an insatiable, immanent becoming.

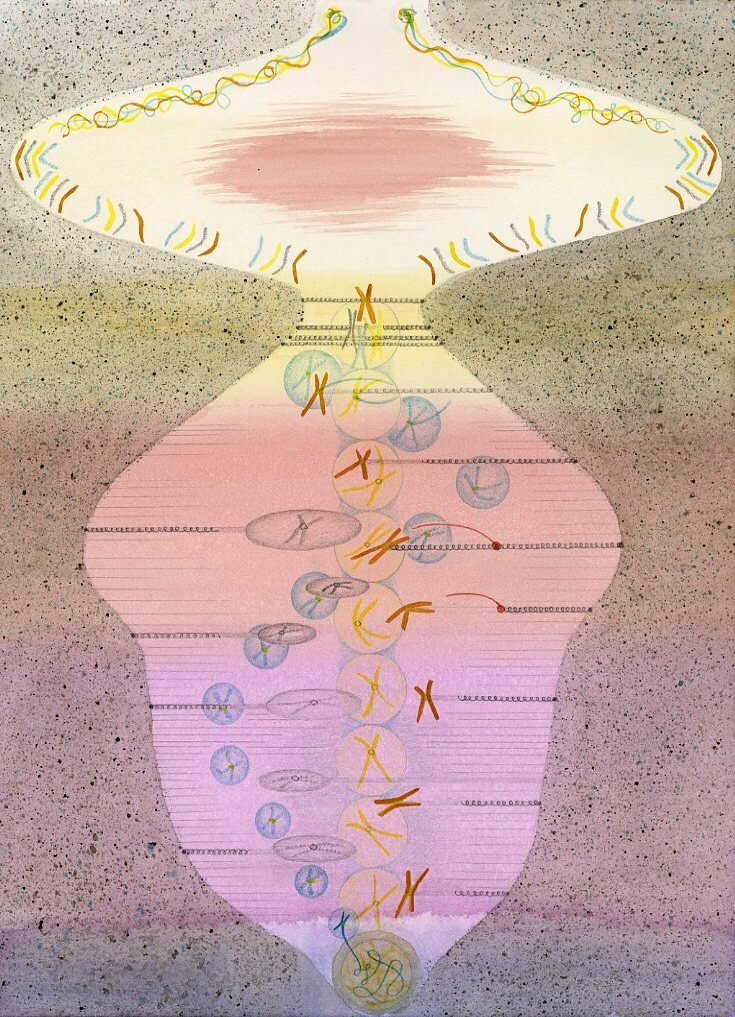

Gemma Anderson’s experimental drawings emerge from an iterative process of (mis-) understanding and reforming in her longstanding collaboration with a biologist (James Wakefield) and a philosopher of science (John Dupré). Following Goethe, they share the question of how to create mental and physical images of living processes without adopting a ‘thing/object’ based vision. They understand living systems as ‘processual’ – as patterns and eddies in a flow rather than static, solid objects in a machine. Anderson’s images represent major processes in living organisms as scores for an orchestra or choreographies of elements working together in a dance reflecting on the shared qualities of pattern and waves of energy.

These drawings make visible aspects of dynamic living processes such as cell division and protein folding (cross species) at the molecular and nano scale. Rather than describing morphological characteristics, the abstract content of the drawings aligns to energetic relationships and movement patterns. They are made in collaboration with cell and molecular scientists and a philosopher of biology as part of an ongoing research project ‘Representing Biology as Process’ [www.probioart.uk].

Artists and Writers

Eileen Agar / Anni Albers / Josef Albers / Sarah Angliss / Consuelo «Chelo» González Amézcua / Gemma Anderson with Wakefield Lab and John Dupré / Anna Atkins / Kirk Barley / Jordan Belson / Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater / Karl Blossfeldt / Carol Bove / Jagadish Chandra Bose / Kerstin Brätsch / Bernd Brabec De Mori / Hildegarde von Bingen / Andrea Büttner / Adam Chodzko / Ithell Colquhoun / Bruce Conner / Brenda Danilowitz / Das Institut / Mirtha Dermisache / Minnie Evans / Cerith Wyn Evans / Charles Filiger / Robert Fludd / Monica Gagliano / Giorgio Griffa / Brion Gysin / Friedrich Wilhelm Heine / Ernst Haeckel / Dr Stephan Harding / Anna Haskel / Tamara Henderson / Channa Horwitz / Textiles from the Huni Kuin (Kaxinawa) people / C.G. Jung / Joachim Koester / Rachid Koraïchi / Hilma af Klint / Emma Kunz / Yves Laloy / Ghislaine Leung / Linder / Simon Ling / Michael Marder / Agnes Martin / André Masson / John McCracken / Terence McKenna / Henri Michaux / Matt Mullican / Wolfgang Paalen / Paul Păun / Stefan A. Pedersen / Santiago Ramón y Cajal / Steve Reinke and James Richards / Edith Rimmington / Adele Röder / Daniel Rios Rodriguez / Rupert Sheldrake / Textiles and ceramics from the Shipibo-Conibo people / Penny Slinger / F. Percy Smith / Janet Sobel / Philip Taaffe / Priscilla Telmon and Vincent Moon / Fred Tomaselli / Delfina Muñoz de Toro / Alexander Tovborg / David Tudor / Lee Ufan / Scottie Wilson / Terry Winters / Adolf Wölfli / Bryan Wynter / Henriette Zéphir / Anna Zemánková / Unica Zürn / artists from the Yawanawá community

The Botanical Mind Podcast Series has been developed and produced with Matt Williams and Alannah Chance.

También te puede interesar

PATRICIA DOMÍNGUEZ: GREEN IRISES

Chilean artist Patricia Domínguez explores healing practices emerging from the points where many worlds meet, clash and overlap as a result of colonial encounters. Rooted in the artist’s ongoing investigation of ethnobotany in South...

Paz Errázuriz: Próceres [National Heroes]

'Próceres [National Heroes]' is a newly printed series (2018) that Paz Errázuriz originally took in 1983. Taken in a government run warehouse in Chile, 'Próceres [National Heroes]' captures the last evidence of toppled Chilean...

Residencies in London And New York Supported by The Caribbean Art Initiative

The Caribbean Art Initiative collaborates actively and on the long-term with cultural institutions and not-for-profit organizations that exhibit and support artists inside the Caribbean region, as well as with organizations outside the region that...