Soto.vibrations 1950–1960

‘Art should evolve with the same seriousness as philosophy, mathematics, and scientific research. For me, art is valuable when this evolution is rationally justified.’

Soto

Renowned as art history’s leading kinetic artist, Jesús Rafael Soto (Venezuela, 1923-2005) explored the dematerialization, or ‘disintegration’ of the art object, breaking new ground while anticipating conceptual strategies to come. Hauser & Wirth in New York presents Soto. Vibrations 1950 – 1960, the first exhibition to focus on the critical first decade of the artist’s life in Paris, curated by Jean-Paul Ameline. A believer in art historical evolution, Soto built upon the work of artistic masters that preceded him in order to challenge figurative tradition via abstraction and repetition. Imbued with vibration and movement, Soto’s early works constitute a breakthrough in his output, laying crucial groundwork for his later kinetic works and the uniquely fluid style that shaped his artistic vocabulary.

The exhibition opens with Soto’s Compositions dynamiques, a series of ten paintings made during his initial year in Paris. First exhibited in the summer of 1951 at the influential Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, an annual showcase that presented a wide range of abstract art, these works reveal Soto’s earliest investigation of geometric abstraction, driven by a subversion of formal compositional principles in painting. Building upon the neoplastic language pioneered by Piet Mondrian, Soto developed his compositions by adhering to a self-imposed, gridded format and a limited color scheme of yellows, reds, blues, and greens. Through his art, Soto wanted to engage viewers as active participants in the process of perception and experimented with the serial repetition of color and geometric forms in an effort to create optical vibrations and what he referred to as ‘the displacement of the viewer.’ As a result, these experimental, serialized paintings convey a sense of depth through an overlay of bright shapes and black delineations, and serve as the foundation of Soto’s trajectory.

Bridging the first and second floors of the gallery is a focused body of work that signals another evolution in Soto’s practice as he begins to experiment in the use of translucent materials. From 1954 to 1957, Plexiglas would become the artist’s primary material. Works such as Points blancs sur points noirs (1954) characterize a radical departure from conventional two-dimensional painting while furthering Soto’s preoccupation with the perception of light, space, and volume, an interest inspired by László Moholy-Nagy’s earlier application of paint on transparent grounds. Duchamp’s influence is equally observed in Soto’s Espiral series, which finds its precedent in Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics), created three decades earlier. “Based upon the work of these artists,” Soto stated, “I began to construct a world, telling myself that I must make use of all the elements they had set forth, but whose implications they had not fully explored.” These implications of optical vibrations and the displacement of the viewer are exemplified in Espiral con rojo (1955), which enacted a seminal shift in his development of kinetic art. Soto exhibited these works for the first time in 1955, alongside Alexander Calder and Duchamp.

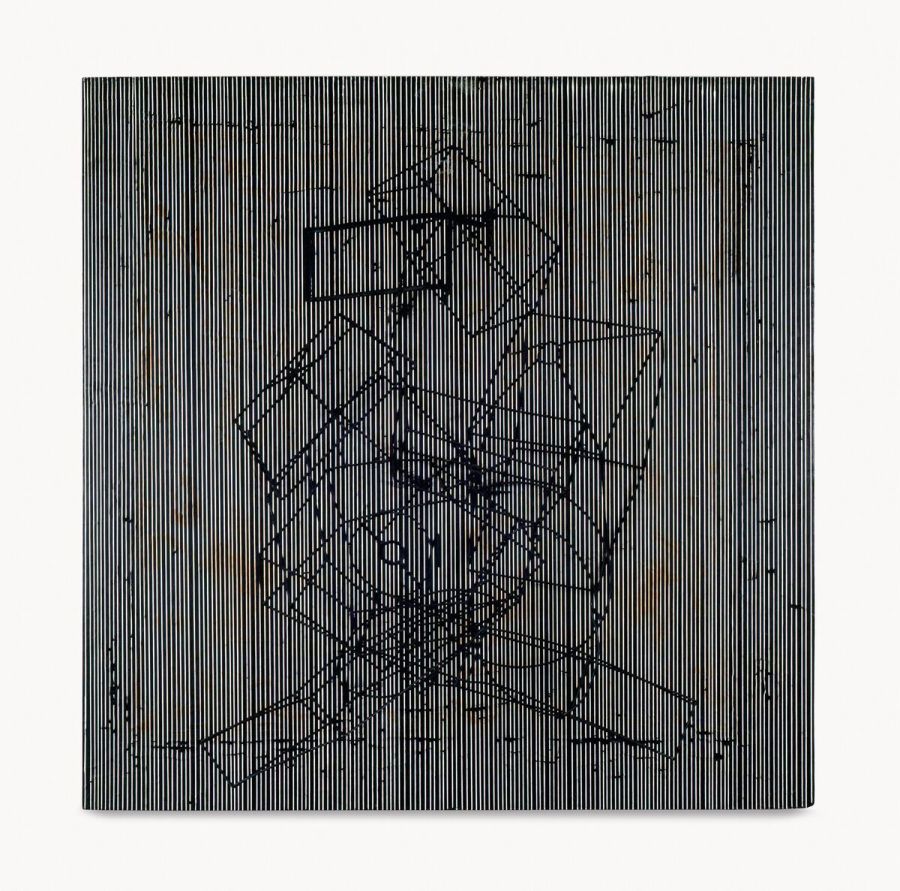

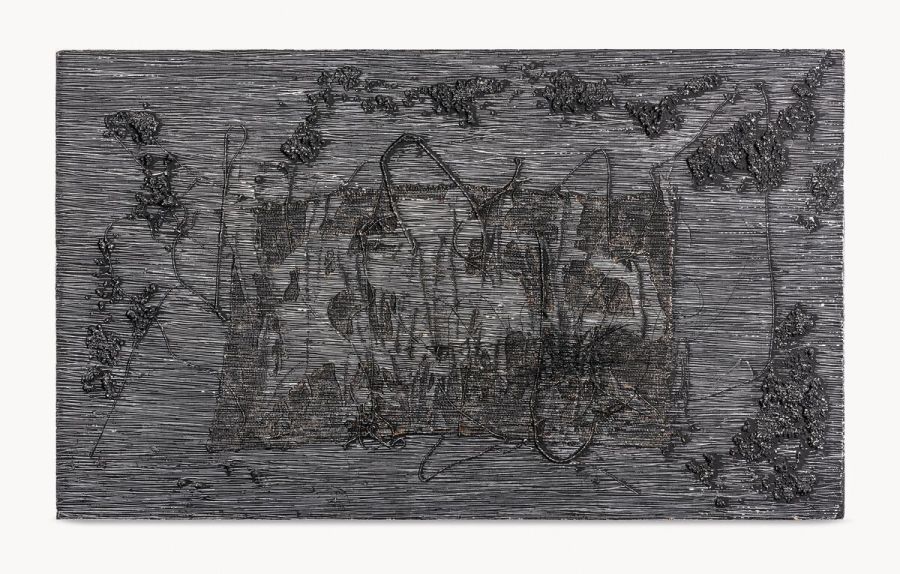

Furthering his experimentation as the decade progressed, Soto simplified his palette to black and white and began incorporating the use of wire after 1957, arranging painted metal into gridded forms against streaked backgrounds, or as found in El juego de la luz (1959), animating a surface of vertical lines through the dynamic juxtaposition of a gestural wire relief, effectively ‘drawing in space.’ These later works unfold onto the third floor of the gallery, where we find Soto extending into the irregular gestures and materials commonly associated with Art Informel, integrating found materials, putty, plaster, and fabrics into his practice. As made visible in Vibración blanca (1960), and other works from the Vibration series, Soto’s desire to break with the stability of forms was an enduring aspect of his oeuvre, one that thrived and then surpassed his seminal Parisian period, heralding his place in the history of avant-garde and kinetic art.

Featured image: Jesús Rafael Soto, Untitled (Barroco Negro), 1961, mixed media on panel, 95.3 x 158.8 x 15.2 cm. Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Alfredo Gugig

También te puede interesar

SIGFREDO CHACÓN: SITUATIONS. EARLY WORK, 1972

Miami Biennale y Henrique Faria Fine Art | New York presentan "Situations", una recreación de la instalación del artista Sigfredo Chacón (Caracas, 1950) presentada originalmente en el Ateneo de Caracas, en 1972. Desafiando la...

ABRAHAM PALATNIK: SEISMOGRAPH OF COLOR

Nara Roesler presents the first retrospective of Brazilian artist Abraham Palatnik (1928-2020) in New York. Curated by Luis Pérez-Oramas, it presents a selection of works that reveal Palatnik’s fundamental role in Brazilian art in...

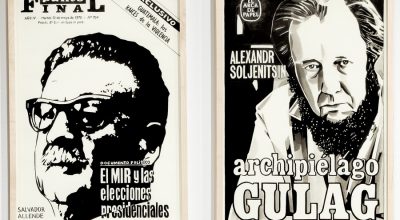

Fernando Bryce:the Decade Review

In Bryce’s review of the decade what is implicit is that world diplomacy was a game played expertly, and exclusively, in the Northern Hemisphere, while the South was dealt and tampered with, most frequently...