A CONVERSATION WITH CECILIA VICUÑA: ARTISTS FOR DEMOCRACY’S ‘FUTURE ARCHIVE’

As part of the Artists for Democracy archival exhibition, hosted simultaneously by the Museum of Memory and Human Rights and the National Museum of Fine Arts, we spoke with the Chilean poet and visual artist Cecilia Vicuña, who has preserved the documents and works of the cultural organization that she co-founded in opposition to the Pinochet dictatorship. Through the research and curatorship of Paulina Varas, this exhibition joins together two institutional spaces to highlight an archive that previously remained unknown. We asked Cecilia Vicuña about this archive, its connection to both spaces, and about the past and present relationship between Chilean art and political struggles.

Translated by Phillip Penix-Tadsen for Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros

Cecilia Vicuña, Francisco Villarroel, Lucy Quezada. Museum of Memory and Human Rights, Santiago, 2013. Photo: Sebastián Mejía

Lucy Quezada: We know the exhibition that brings you here to Chile, Artists for Democracy, is being held in the Museum of Memory and Human Rights as well as in the National Museum of Fine Arts. How do you think that these two spaces are connected through the exhibition of this archive? Do you sense any discursive connection between these two museums?

Cecilia Vicuña: My work, in the way that I conceive of it and the way that many others interpret it, takes in everything. What I do are songs, performances, installations, written works, books, sculptures; that is, my work is completely multidimensional. Also, I’ve worked with a lot of people from the very beginning. I have founded or been a member of collectives that have now become part of history. At the same time, while I may come from a family of artists, my ancestral roots are ancient, going back thousands of years, in Chile as well as in Europe and Africa. Therefore, my archive is a kind of multidimensional document that involves all of my connections and relationships, even the ancestral ones. The archive is not just something physical that is kept in a box, it’s also all of those relationships.

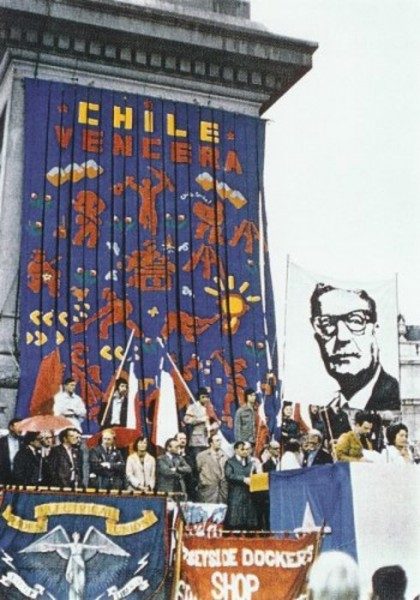

When Paulina Varas started doing her research and invited me to exhibit work in the Museum of Memory, it seemed like a great idea, but I instantly realized that there wouldn’t be enough space here to put up the monumental and most well-known work by Artists for Democracy, which is the banner that John Dugger made for the biggest political protest in the history of England. On that occasion, nearly 10,000 people assembled in Trafalgar Square to protest the military coup in Chile, which resulted in this truly monumental and historical work, which had never been shown in Chile. An immense space was needed to exhibit it, which is why it’s there in the central hall of the National Museum of Fine Arts, next to the sculpture of El Giotto by my great-grandfather Carlos Lagarrigue.

On the other hand, the relationship between the two museums is very tense, in that they are two very different worlds, socially, artistically, and aesthetically. But right now that tension also implies a connection, because they’ve collaborated together several times now, which seems like a great thing to me; it’s like the two ends of Chile are connecting.

John Dugger, Chile Vencera Banner, 1974, textile, mixed media. Installation view at Trafalgar Square © John Dugger

Francisco Villarroel: The movement that produced Artists for Democracy was brought about in a very different context than the present, in relation to the military coup of 1973. To give a more contingent reading of that monumental work you’ve mentioned, what do you think of the present state of our democracy, in comparison to that past?

CV: I think that the importance of bringing this work to Chile now is that, right now, Chile must decide if it will carry on with a hijacked democracy, a false democracy, a made-up democracy (like the one we’ve had from the dictatorship forward), or if we’re going to take back the right to a participatory democracy as it was conceived in Chile through the Political Constitution that existed prior to the military coup. The movement in the Constituent Assembly is a very powerful moment that Chile is experiencing, and the situation that the students have brought about is really important too. And so this work is dedicated to this moment. The exhibition wouldn’t have been possible two years ago, nobody would have even thought of doing a show like this.

On the other hand, Artists for Democracy has been completely erased from Chilean, Latin American and European history. Why the resurgence now? It’s because the young people want it. They’re asking for it without saying so. What I mean by that is that the archive is a network of relationships. This work is related to the present even though it was made 40 years ago, which is why the archive exists, because our conversation is the archive. To give an example, in my text I talk about Edward Snowden, who to me represents the youth of today: a person who sacrificed his life, as he said, for a “moment of conscience.” Snowden is giving his life like Allende gave his: that fact has infinite value. And the society we’re living in now has denied that possibility, that potentiality, that value. Everything revolves around the “I,” it’s a culture of the ego. Therefore, I think that the call that needs to go out to artists is for a participatory democracy. It’s no longer merely a political question, it’s a question of the survival of humanity, of the survival of the planet.

Several people have told me that nowadays they are in a bubble, in a different world, and they’re not participating in the struggle for participatory democracy. Note: they don’t participate in the struggle because of the participatory part. When we did Artists for Democracy everything was dedicated to participation. I did a participatory painting; have you heard of a “participatory painting”?

LQ: As a matter of fact, I have. During the uprisings in 2011 there was a strong turn toward visuality in the protests, and certain artistic manifestations that don’t receive a lot of attention—although they are known among the universities and colleges—came about in a moment during which those types of participatory relationships were taking place: large-scale collective works were being made that had an impact on the protest, and that represented the rest of the protestors who were expressing themselves through their own disciplines.

CV: Well, that’s Artists for Democracy.

LQ: It’s the same spirit.

CV: Exactly. When that spirit is manifested and becomes present, an exhibition like this is not only possible but it makes sense. Because I’m interested in coming into contact and connecting with that spirit. I’m not interested in connecting to the world of power or the world of artifice. I’m interested in what’s going on right now, when young people are deciding to make works of art that are participatory, that are connected and that are there, in the moment and with the people in the street. That’s simply fantastic.

LQ: Right, there’s a moment coming about in which, because of this connection with archives, they’re reactivated in a historical and spiritual way, and they grow stronger. That type of treatment of the archive is notable after all the commemorations of the 40th anniversary of the coup last year. The exhibition could be a “tail end” of that, but as you say, it is “its own” moment.

CV: I think it’s a “tail end” of that and at the same time, it makes me wonder. I was not present to see all of those exhibitions, but I wonder how many presented the archive as a thing of the future. Because that’s the meaning of this archive: it is a future archive. An archive that will exist if you wish for it to exist, that’s my perspective. Paulina Varas, a young curator, is seeking that history. She found a reference in a sentence in a book in English, and thanks to that I’m here. So for me it’s very important that I didn’t come out and propose this, because it wouldn’t have made sense for me to propose it. However if it comes from another direction, it’s a different movement, one that starts from below, one that is born of life itself.

Cecilia Vicuña during the installation of the Artists for Democracy exhibition, in the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, Santiago, 2013. Photo: Macarena Cortés

FV: One characteristic of your work is the creation and participation of collectives or spaces of relation between multidisciplinary artists, as was the case with Tribu No [No Tribe]. What was it, exactly, that created that coming together and that coordination of the movement at that moment?

CV: A wish. The wish to be completely free and to be in a permanent state of joy. That was possible in the sixties, because the whole planet was part of it; it wasn’t just one young girl in Santiago. If you read my erotic poetry from those years (which for a long time was censored), you can see that child, and it’s a precious thing to have that kind of innocence… It’s a nudity where the clitoris is like a flower, not a perverted clitoris, it’s not a corrupted thing. That was what was made possible by Tribu No: a completely “over-the-top” love that we had between us, and such a wild happiness, that we were celebrating being here. Beyond that there was the political dimension, because in those years there was the same type of confluence or convergence as is happening today. The spiritual, the political, the existential, the ecological; everything was coming together. And that special situation gave you a consciousness of the present, a consciousness of what was possible for us as humanity, as an evolutional leap.

Then came the repression. The killing. The savage capitalism. Just recently, I believe, young people have become like we were back at that time.

FV: These young people of today are experiencing something that involves protests and uprisings that go beyond the milestones of 2006 and 2011, as a lot of the repercussions can still be felt. What do you think about this common gesture or practice of protest? Is it possible for a new generation of artists to enter into dialogue with protest?

CV: Protest is just one dimension. The most important thing that we have to recover (especially here in Latin America) is multidimensionality, which is our pre-Columbian legacy and is rooted in our mixed ethnicity. That multidimensionality for me involves recovering what we are as potential beings in terms of our neurons or our circulation of blood and oxygen, but also the circulation of community life, of collective life. Protest is a very important civil right, which is why artists who break away from that, it’s as if they were cutting off their nails, cutting off their hair, cutting off an arm.

We have to bring back all of those discussions. For example, there has always been the idea that the political artist is a square peg just like an ideologue. But there are people like Lucy R. Lippard, who in her essay published in our catalogue mentions my work as a political act of another type: a type of political art that is spiritual, abstract, minimal and doesn’t fit into any existing definitions. It broaches a sensibility that is simultaneously aboriginal and futuristic. In the group of people with whom I work I feel that there is a desire to transform life, to transform the present. Old people, like me, we continue to connect to that and we keep going along the same lines, as if 40 years hadn’t passed by for us.

LQ: In the sixties there was a kind of political and cultural network that came about (which to an extent ceased after Allende’s presidency) that included important people such as Nemesio Antúnez. He was a political artist with a strong vision of conceptual art, which he mixed together with that kind of art that harmonizes with a political form, and in spite of that, is not pigeonholed as the usual demagogic enlightenment.

CV: Nemesio Antúnez was a very important person in my life. When he took on the role of director of the National Museum of Fine Arts, Nemesio went on TV saying that he was going to completely transform the museum, which up to then was a 19th-century mausoleum that you couldn’t even go into. At that moment, he said: “I’m going to open up the museum to young people.” The next day I went running from Plaza Italia to the Museum, went into his office (nobody stopped me, neither the secretaries nor the guards), and he says, “Who are you?” and I, panting, reply: “I’m Cecilia Vicuña.” He says, “Oh! I know you… (he had read my poetry in New York); What do you want?,” and I say to him: “I want to fill the museum with leaves.” He said: “Oh… Let me think about it,” and three days later he called me and gave me the OK. I was a girl who had come out of nowhere, a young kid, and that was my first exhibition: Otoño [Autumn], in the Museum of Fine Arts.

That same year Juan Downey, Gordon Matta-Clark, Juan Pablo Langlois and I were doing those kinds of things. There was a fantastic kind of confluence that came about and also had its parallels in London, Buenos Aires, New York…When I went to London, my book was published by the main publisher for the Fluxus Movement, but it wasn’t that I was part of Fluxus, it was just that for Fluxus what we were doing in Santiago was connected in a completely natural and organic way.

FV: It’s interesting how those same situations and convergences were replicated and communicated, it being so totally improbable that you, at just 16 years of age, could have had contact with those foreign movements. There was no possibility of plagiarism on your part or reproduction by mere assimilation…

CV: What you’re suggesting is very smart. For example, I heard “conceptual art” for the first time after having done the work Otoño (I heard the term because Nemesio Antúnez did a radio show where he spoke about conceptual art). Recently the MoMA did an exhibition, which is the history of drawing and how it comes out of two-dimensionality and enters into space. And my work was there as one of those globally pioneering works, not just in Latin America, but everywhere, because that was exactly what I was starting to do. Like you say, I was doing it here, but there were also people doing it in other parts of the world without being in direct contact. This indicates to me that there is a connection that functions at another level between the imaginary of an era and the citizens who are alive at that moment.

LQ: Changing the topic, in the last presidential elections, Michelle Bachelet was reelected as President of the Republic, and in Chile you are known for a letter that you wrote directly to her in 2006. It was a letter about Pascua Lama in which you condemned the assault on the glaciers. Without a doubt, at that point you placed a lot of hope in Bachelet. Do you think that hope could possibly turn into some type of change with the coming government?

CV: Half of my body says, “No way, absolutely not.” The Chilean people have really been let down from the dictatorship up to the present. The whole promise of liberty and democracy has not come about. It’s been a disaster that perhaps we’ve all contributed to; we’ve all taken part in silencing that true hope that came about after the “No.” But the other half of my body says, “Absolutely, but it depends on us.” That is, we can’t wait for her to do something: it depends on us, it depends on what the people demand, ask for, and present. For example, on opening day I’m going to do a performance dedicated to the destruction of the 26 glaciers that run from Aconcagua to Tinguiririca, which is a new plan of CODELCO’s that most people aren’t aware of. If that occurs, the area will become the most polluted in Chile: we are going to kill all of those valleys where we live, the water is going to run out, they’re going to make the biggest open-cut mine in the world in that location. Just like I told Bachelet at that time, water is gold, and even still that’s the change that they make. Water is gold: because that phrase is the phrase of this moment in human history, it’s the phrase on everyone’s lips.

FV: It’s the idea that the citizens should push change; Bachelet alone won’t really do anything, but rather it’s the community that must pave the way to make change possible. What do you think about the options for an effective democracy with the system that we have in place today?

CV: Zero. The most important movement right now is the Constituent Assembly: as long as the Political Constitution remains unchanged, where is the participation? Where is the collective intelligence? Where is the music that belongs to all of us? The tradition of this land is for all to unite and become a single instrument creating collective music. That is the idea that the capitalist system has tried to cover up and destroy. Why are Mapuche children tortured? Why are grandmothers tortured? Why are even the machis tortured? Because it’s a question of uprooting the spirit, ripping out the newen. But that newen is in all of us, you can’t look the other way and ignore that.

It seems to me that this is a moment of total emergence. For example, I’ve made a film titled Kon Kon that deals with the death of the sea. In the village of Con Con you can no longer eat fresh fish: everything ran out, because the trawling ships that belong to the Chilean senators themselves have destroyed Chile’s ocean. What kind of democracy is it when the senators themselves are destroying everyone’s ocean? This is a fantasy, a negative fantasy, a fantasy of terror.

También te puede interesar

CINCO MUESTRAS EN M100 EXPLORAN LAS RELACIONES ENTRE POLÍTICA Y CELEBRIDAD

El artista como activista, la celebridad como activismo social, la política como celebridad. Un terreno empantanado, de relaciones difusas, de intereses creados y conflictos de interés. Aquí, y en su convergencia con el arte,…

CANCIÓN NACIONAL. ¿SIGUE SIENDO CHILE LA COPIA FELIZ DEL EDÉN?

¿Cuántas veces hemos entonado la Canción Nacional sin pensar en lo que representan sus palabras, sus imágenes, sus símbolos? ¿Es esta acaso una metáfora del país que fuimos o del que alguna vez aspiramos...

MINDS RISING, SPIRITS TUNING: 13° BIENAL DE GWANGJU

La 13° Bienal de Gwanju profundiza en un amplio conjunto de cosmologías para activar la diversidad de formas de inteligencia, sistemas de vida planetarios y métodos de supervivencia comunitaria, y cómo estos compiten con...