CRISTÓBAL LEHYT: EL OBJETO TRABAJADO

Algunos temas se han repetido con frecuencia en los últimos años en el trabajo de Cristóbal Lehyt. Tal vez entre los más importantes están el examen de la relación entre el trabajo y la producción, entre la fabricación de un objeto y su consumo, y entre el objeto artístico, su fabricante y el espectador. Utilizando el paisaje, el objeto artesanal, la estructura de clases, la historia de la industria y el trabajo, analiza las relaciones artificiales y construidas entre estas ideas y el desarrollo de la identidad nacional.

Entre sus trabajos más recientes hay uno que aborda todas estas ideas. Su exposición, Cristóbal Lehyt: If Organizing Is the Answer, What’s the Question? se presentó en el Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts de la Universidad de Harvard entre el 4 marzo y el 4 abril de 2010. Esta exposición incluyó un contenedor de gran escala hecho de madera contrachapada situado en el centro del espacio. En el interior del contenedor, el artista colocó cientos de pequeñas esculturas. Para subrayar el abismo real y simbólico entre los objetos en el contenedor y el espectador, perforó una de sus paredes e hizo una pequeña ventana a través de la cual los espectadores veían las obras con dificultad. El contenedor iba acompañado de una serie de 260 pinturas. Estas fueron instaladas en las paredes alrededor de la pieza central y mostraban imágenes de paisajes de ensueño. Símbolos de cada uno de los días laborables del año, las pequeñas pinturas evocan el tiempo y el espacio en el que el trabajo es llevado a cabo, imitando el esfuerzo del espectador para acceder a las obras dentro de la gran caja de madera.

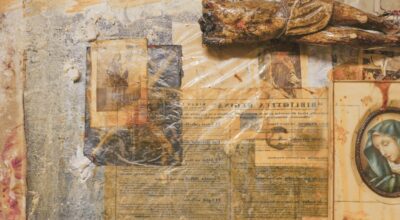

Otra obra que también abordó los asuntos del trabajo y el consumo con el añadido del nacionalismo cultural es su gigante Pomaire del 2009. Esta escultura es un recipiente grande, de 36 metros de longitud, y tiene la forma del contorno geográfico de Chile. Pomaire es un pequeño pueblo cerca de Santiago conocido por su tradición alfarera. La forma de madera contiene los restos de miles de vasijas de cerámica rota, lo que representa el legado de un pasado violento y sugiere una ruptura de la imagen de sí mismo que tiene el país. En un trabajo que ha venido desarrollando desde el año 2003, El Norte, el artista ha explorado la cultura del norte de Chile a través de su televisión y medios impresos, grabaciones de audio, la manipulación de la luz y la presentación de la información, cuyo significado no se hace inmediatamente evidente para el espectador. Entre las imágenes de este trabajo están las representaciones del interminable paisaje del desierto estrechamente relacionado con el árido norte de Chile. También se incluyen imágenes de la población indígena, imágenes de medios impresos locales fotografiadas nuevamente y vistas aéreas del desierto. Esta insinuación de claves visuales que buscan aludir a la información, o la inclusión de textos que son a la vez informativos y engañosos, también forman parte de la obra del artista, que juega con los significados supuestos y reales de los textos públicos y sus intenciones.

Subrayando su exploración del norte de Chile está un grupo de esculturas abstractas que el artista ha realizado a partir de materiales inesperados, tales como cuerdas, madera, cola y yeso o compuesto para mampostería. El artista adapta estos materiales de «baja tecnología» a sus obras esculpidas, hechas en el lenguaje propio del modernismo: abstracción pura. Esta contradicción entre un vocabulario de las bellas artes y los materiales de contratistas, carpinteros y jornaleros también es típico de su obra. Las formas orgánicas de las esculturas también entran en contradicción con su ubicación austera, encima de una larga mesa de trabajo sostenida por dos caballetes. Como muestras biológicas dispuestas para la observación, evocan las obras de Gabriel Orozco o Louise Bourgeois. Estos dos artistas también han presentado una variedad de objetos que fusionan el lenguaje de la abstracción modernista con una presentación humilde que sirve para dislocar los objetos y, en ocasiones, al espectador.

Justo antes de su exhibición en Harvard, el artista presentó su Ecstasy of St. Teresa (“El éxtasis de Santa Teresa”) en Gasworks Gallery de Londres en marzo de 2010. Una colaboración entre Lehyt y Alessandra Pohlmann, el trabajo de gran tamaño fue creado intencionalmente grande para llenar un espacio pequeño. Actuando como una metáfora contemporánea de la sensibilidad del Barroco, la monumental cortina reinscribe, de un modo muy físico, gran parte del impacto emocional del Barroco. Obligando a los espectadores a pasar por el apretado espacio, los pliegues del paño son tanto el tema como los elementos activadores de la obra. La referencia a la magnífica obra de Bernini también pone de relieve los esfuerzos constantes de Lehyt por dar al espectador la oportunidad de experimentar el trabajo implícito en la realización de una obra de arte y su impacto emocional. Esta obra fue creada sobre dos caballetes, lo que la hace parecer al mismo tiempo ligera y pesada, como en la obra original de Bernini. El artista examina de cerca la idea de tallar una nube a partir de un pedazo de mármol macizo, así como la experiencia del espectador de esta aparente contradicción. La preocupación del maestro barroco con el movimiento, el ritmo, y el impacto emocional de la obra se refleja en el super agrandamiento que hace Lehyt de su objeto, un detalle gigante del original en el que la representación del movimiento es una fuerza central.

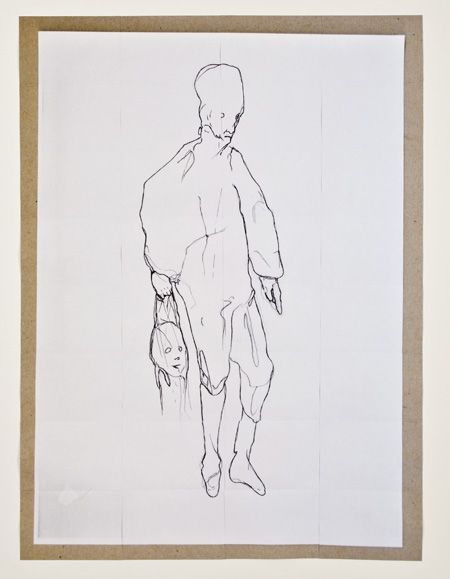

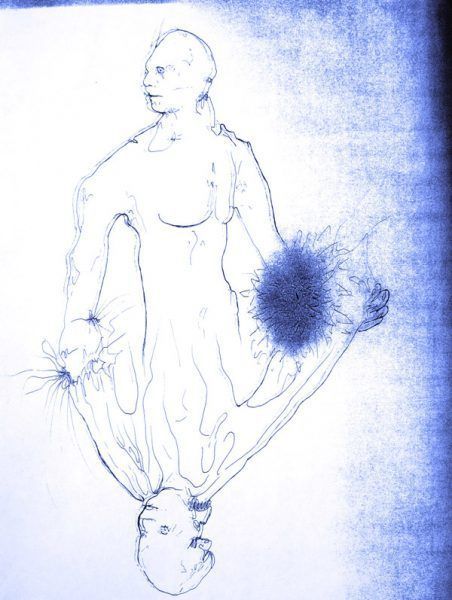

Simultáneamente con la presentación de este trabajo realizado en Gasworks, el artista también exhibió un proyecto en solitario en la House of Propellers, también en Londres. Esta exposición contó con obras de su serie «El Norte” en una variedad de medios, incluyendo dibujos, fotografías, vídeos y esculturas. Para este espacio, añadió una serie de retratos de personas de Stuttgart hechos específicamente para una exposición de 2008 en Alemania. En conjunto, las obras de El Norte y los retratos de Stuttgart tienen por objeto la exploración de las variadas nociones de lugar. Los retratos, creados a lápiz, evocan un mundo onírico en el que el artista se imagina bajo la apariencia de otro. Aunque se leen como retratos, las caras y cuerpos carecen de detalles suficientes para ser identificables. ¿Son figuras reales, personajes de ficción creados por el artista o una paradójica combinación de ambos? Las órbitas oculares vacías y las poses torpes evocan un drama visceral, a lo Bacon. Es evidente, sin embargo, que están estrechamente ligadas a su propia visión de la figura humana y su representación emocional.

La más reciente exposición Cristóbal Lehyt tiene lugar en la Galería Patricia Ready de Santiago, que presenta obras de las series Proyección Dramática (Vitacura) y Esculturas. Al igual que con las obras anteriores, estos proyectos vuelven a difuminar los límites entre el objeto común, la obra de arte y el paisaje de lo cotidiano. Este conjunto de obras está pensado como una especie de retrato de la zona de Santiago en el que se encuentra la galería, en concreto el sector entre la calle Alonso de Córdoba y la avenida Vitacura. Como señala el artista, «es la comuna en que nací, donde crecí y donde aún vive parte de mi familia”.

Las obras consisten en un conjunto de cinco dibujos sobre Vitacura. Hechos en un espíritu similar a los dibujos automáticos del surrealismo, estos trabajos son creados por el artista durante un estado de trance que dura días. Durante este período, Lehyt se concentra en los años en que vivió en la zona. Él afirma que las obras «están hechas sin control evidente, salen del momento creado por la concentración, el aburrimiento, el ensimismamiento y, al mismo tiempo, la pérdida de control porque surgen de ese proceso sin un control aparente”. Al igual que su retratos de Stuttgart, estos dibujos evaden una clara distinción entre arte y realidad, evocando un paisaje que está impregnado de detalles del mundo real y la influencia psicológica de un lugar determinado. El título de la serie se plantea también sobre la naturaleza barroca de creación de imágenes. El artista astutamente observa: «toda obra de arte es una proyección dramática.» Las proyecciones dramáticas son dibujadas, fotografiadas, ampliadas, impresas, alteradas en color y luego reconfiguradas en tamaño natural. Las esculturas vagamente recuerdan objetos y formas familiares al espectador, incluidas referencias al Modernismo de mediados del siglo XX, patrones orgánicos y alusiones a cosas tanto visibles como invisibles. Al igual que las figuras de Miró o Arp, sus figuras esculpidas parecen moverse y transformarse a medida que se observan.

En cuanto a la historia del arte, el trabajo de Cristóbal Lehyt se vincula al de su predecesor, Francisco Brugnoli, en particular en cuanto al tipo de gestos que ambos artistas hacen, y los significados que estos gestos revelan al espectador. Ambos artistas no pueden estar simplemente atados a un solo medio. De hecho, su trabajo evoca precisamente una facilidad que va desde la escultura a la pintura, al video, la instalación y las obras en papel. Ambos artistas utilizan una variedad de objetos ordinarios intervenidos o imágenes existentes (incluyendo fotografía y vídeo) con el fin de explorar el desarrollo y los resultados de los diversos sistemas sociales, incluidos la educación y los procesos políticos. Destacando las delicadas y a veces oscuras conexiones entre formas, contenido, ideas, conocimiento y los objetos de arte, Cristóbal Lehyt crea narrativas que abordan tanto lo específico como lo universal, lo nacional y lo global, lo personal y lo político.

Cristóbal Lehyt (1973) Vive y trabaja en Nueva York. Sus exposiciones individuales incluyen UAG / Room Gallery, UC Irvine; Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, y la Fundación Telefónica de Chile. Entre sus exposiciones colectivas están la Bienal del Mercosur (2009), New Ghost Entertainment—Entitled, en Or Gallery y Kunsthaus Dresden (2006); When Artists Say We, Artists Space (2006); Metaphysics of Youth, Fuori Uso (2006); la Bienal de Shanghai (2004), The Freedom Salon, Deitch Projects (2004); The American Effect, Whitney Museum of American Art (2003); Freewaves Latin America, MoCA Los Angeles (2002), así como exposiciones en Santiago, Bogotá, Caracas, Ciudad de México , Berlín, Viena, Beijing y Río de Janeiro. Ha recibido la Beca Art Forum de la Universidad de Harvard y la Beca Guggenheim. Estudió en el Hunter College de Nueva York y ha participado en el competitivo Whitney Independent Study Program.

Traducción al español: Alejandra Villasmil

A few themes have recurred frequently over the last few years in Cristobal Lehyt’s work. Perhaps among the most important are the examination of the relationship between labor and production, between the fabrication of an object and its consumption, and between the art object, its maker, and the spectator. Using the landscape, the craft object, class structure, the history of industry and labor, he examines the artificial and constructed relationships between these ideas and the development of national identity.

Among his most recent work there is one that addresses all of these ideas. His exhibition, Cristobal Lehyt: If Organizing Is the Answer, What’s the Question? was presented at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts from March 4 to April 4, 2010. This exhibition featured a large-scale container made from plywood placed in the center of the space. Inside the container, the artist placed hundreds of small sculptures he produced. To underscore the real and symbolic gulf between the objects in the container and the spectator, he pierced a wooden wall of the container with a single tiny window through which viewers had to struggle to see the works. Accompanying the large container were a series of 260 paintings. These were installed on the walls around the center piece and featured images of dreamy landscapes. A symbol for each of the work days of the year, the small paintings evoke the time and space in which work is undertaken, labor and effort are expended, mimicking the effort of the spectator in accessing the works inside the large plywood box.

Another work that also addressed issues of labor and consumption with added layers of cultural nationalism is his giant Pomaire from 2009. This sculpture is a large container, 36 meters in length, and shaped like the geographic outline of Chile. Pomaire is a small town near Santiago that is known for its history of pottery making. The wooden form contains the remains of thousands of broken ceramic pots, representing the legacy of a violent past and suggesting a rupture of the country’s image of itself. In a work he has been developing since 2003, El Norte, the artist has explored the culture of the north of Chile through its television and print media, audio recordings, the manipulation of light, and the presentation of information, the significance of which is not immediately apparent to the viewer. Among the images in this work are representations of the endless desert landscape that is closely associated with the arid north of Chile. Images of the indigenous population are also included, as are re-photographed images from local print media, and aerial views of the desert. This suggestion of visual clues intended to allude to information, or the inclusion of texts that are both informational and misleading, are also part of the artist’s work, playing with the supposed and real meanings of public texts and their intentions.

Underscoring his exploration of the north of Chile are a group of abstract sculptures the artist has made from unexpected materials such as string, wood, glue and drywall or joint compound. The artist purposefully adapts these “low-tech” media to his sculpted works, made in the art historical language of modernism—pure abstraction. This contradiction between a high art vocabulary and the materials of contractors, carpenters, and day laborers is also typical of his work. The organic forms of the sculptures are also posed in contradiction to their austere placement, atop a large worktable set, again, atop two sawhorses. Like biological samples set out for observation, they evoke the works of Gabriel Orozco or Louise Bourgeois. Both of these artists also have presented a variety of objects that fuse the language of modernist abstraction with a humble presentation that serves to dislocate the objects and, occasionally, the viewer.

Just prior to his Harvard show, the artist presented his Ecstasy of St. Teresa at Gasworks Gallery in London in March 2010. A collaboration between Lehyt and Alessandra Pohlmann, the oversized work was purposefully created large to fill a small space. Acting as a contemporary metaphor for the sensibilities of the Baroque, the monumental drapery re-inscribes, in a very physical way, much of the emotional impact of the Baroque. Forcing viewers to squeeze through the space, the drapery folds are equally the subject and the activation of the work. The reference to Bernini’s magnificent work also underscores Lehyt’s constant efforts towards giving the spectator the opportunity to experience the labor involved in the realization of a work of art and its emotional impact. This work was set atop two sawhorses, making it seem simultaneously light and heavy, as with Bernini’s original work. The artist examines closely the idea of carving a cloud from a piece of solid marble as well as the spectator’s experience of this seeming contradiction. The Baroque master’s concern with the movement, rhythm, and emotional impact of the work is reflected in Lehyt’s super-sizing of his object, a giant detail of the original in which the representation of motion is a central force.

Simultaneously with the presentation of this work made at Gasworks, the artist also exhibited a solo project at House of Propellers, also in London. This exhibition featured works from his El Norte series in a variety of media including drawings, photography, video works, and sculpture. To this venue, he added a series of portraits of people from Stuttgart made specifically for a 2008 exhibition in Germany. Taken together, the works from El Norte and the Stuttgart portraits are intended as explorations of the varied notions of place. The portraits, created in pencil, evoke a dream-like world in which the artist imagines himself in the guise of another. Though readable as a portrait, the faces and bodies lack just enough detail to be identifiable. Are they real figures, fictional characters created by the artist, or a paradoxical combination of both? The vacant eyes and awkward poses evoke a visceral, Baconesque drama. Clearly, however, they are closely tied to his own vision of the human figure and its emotional representation.

Cristobal Lehyt’s most recent exhibition took place in Santiago’s Galería Patricia Ready, featuring his Dramatic Projection and Sculptures. Like with prior works, these projects again purposefully blur the boundaries between the ordinary object, the work of art, and landscape of the everyday. This set of works is imagined as a kind of portrait of the part of Santiago in which the gallery is located, specifically the neighborhood between Alonso de Córdoba Street and Vitacura Avenue. As the artist notes, “it is the neighborhood in which I was born and raised and where a part of my family still lives today.” The works titled Dramatic Projection address Vitacura and consist of a set of five drawings.

Made in the spirit of Surrealism’s automatic drawings, these are created by the artist during a trance-like state that lasts for days. During this period, the artist concentrates on the years in which he lived in the area. He states “the works are made without obvious control, they are spontaneous, and develop out of concentration, boredom, total absorption and, at the same time, the loss of control because they arise from this process without any apparent control.” Like his portraits from Stuttgart, these evade a clear distinction between art and reality, evoking a landscape that is infused with details from the actual world and the psychological influence of a particular place. The title of the series bears also on the Baroque nature of image making. The artist astutely notes, “every work of art is a dramatic projection.” The dramatic projections are drawn, photographed, enlarged, printed, altered in color, and then reconfigured in life-size. The related sculptures vaguely recall objects and forms already familiar to the spectator, including references to mid-twentieth century Modernism, organic patterns, and allusions to things both visible and invisible. Like the shapes of Miró or Arp, his sculpted figures seem to move and transform as they are viewed.

In terms of the history of art, Cristobal Lehyt’s work relates to that of his predecessor, Francisco Brugnoli, particularly in the kinds of gestures that both artists make, and the meanings these gestures reveal to the spectator. Both artists cannot be simply tied to a single medium. Indeed, their work evokes precisely a facility that ranges from sculpture to painting, to video, to installation, to works on paper. Both artists use a variety of intervened ordinary objects or existing images (including photography and video), in order to explore the development and outcomes of various social systems, including education and political processes. Underscoring delicate and sometimes obscure connections between forms, content, ideas, knowledge, and the objects of art, Cristobal Lehyt creates narratives that equally address the specific and the universal, the national and the global, the personal and the political.

Cristóbal Lehyt (1973) Lives and works in New York. His solo exhibitions include UAG/Room Gallery, UC Irvine; Künstlerhaus Stuttgart; and Fundación Telefónica, Chile. Group exhibitions include the Mercosur Biennial (2009); New Ghost Entertainment—Entitled, Or Gallery and Kunsthaus Dresden (2006); When Artists Say We, Artists Space (2006); Metaphysics of Youth, Fuori Uso (2006); the Shanghai Biennale (2004); The Freedom Salon, Deitch Projects (2004); The American Effect, Whitney Museum of American Art (2003); Freewaves Latin America, MoCA Los Angeles (2002), as well as exhibitions in Santiago, Bogotá, Caracas, Mexico City, Berlin, Vienna, Beijing and Rio de Janeiro. He has received the Art Forum Fellowship, Harvard University and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship. He has studied at New York City University’s Hunter College and also has participated in the competitive Whitney Independent Study Program.

También te puede interesar

LAS PINTURAS CORPORALES DE CARLOS LEPPE

Mucho se ha hablado de Carlos Leppe en los últimos meses, en parte gracias a la brillante exposición montada en el Bellas Artes. Paralelamente, y desde una vereda bastante menos espectacular, la Galería Aninat...