MIGUEL ÁNGEL ROJAS: YO, USTED Y EL CLAN

Yo, usted y el Clan at Casas Riegner, Bogotá, surveys the career of famed Colombian artist Miguel Angel Rojas. A leading figure in the history of conceptual art and a chameleon of medium and form, Rojas has recently been the subject of another retrospective. Only last year, his expansive show at the Museo de Arte Moderno Bogotá (MAMBO) Regreso a la Maloca (2021) placed a particular emphasis on the exploitation and conflict in the Amazonas region in southern Colombia. At Casas Riegner, the emphasis is a bit broader and retrospective in tone.

The artist’s characteristic attention to queer visibility, the violent and poetic resonances of the armed conflict, and drug trafficking is present throughout the exhibition, as is his incisive attention to how the materiality of his pieces can evoke these labyrinthine geopolitical events. While Yo, usted y el Clan may not reshape viewers’ approach to Rojas’ practice, it succeeds as a show which iterates on what has come before. Pieces produced in the last year since the MAMBO show abound, as do never-before-seen pieces from series the artist has been working on since the 1970s. Ultimately, Yo usted y el Clan is a must see for fans of Rojas’ work, and an excellent opportunity to immerse oneself in the Colombian master’s engrossing and ever-expanding production.

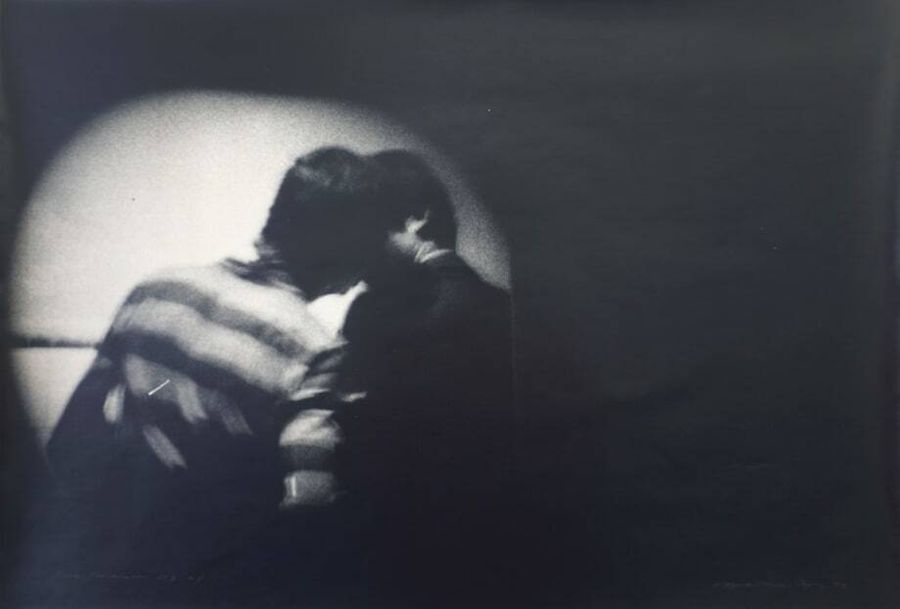

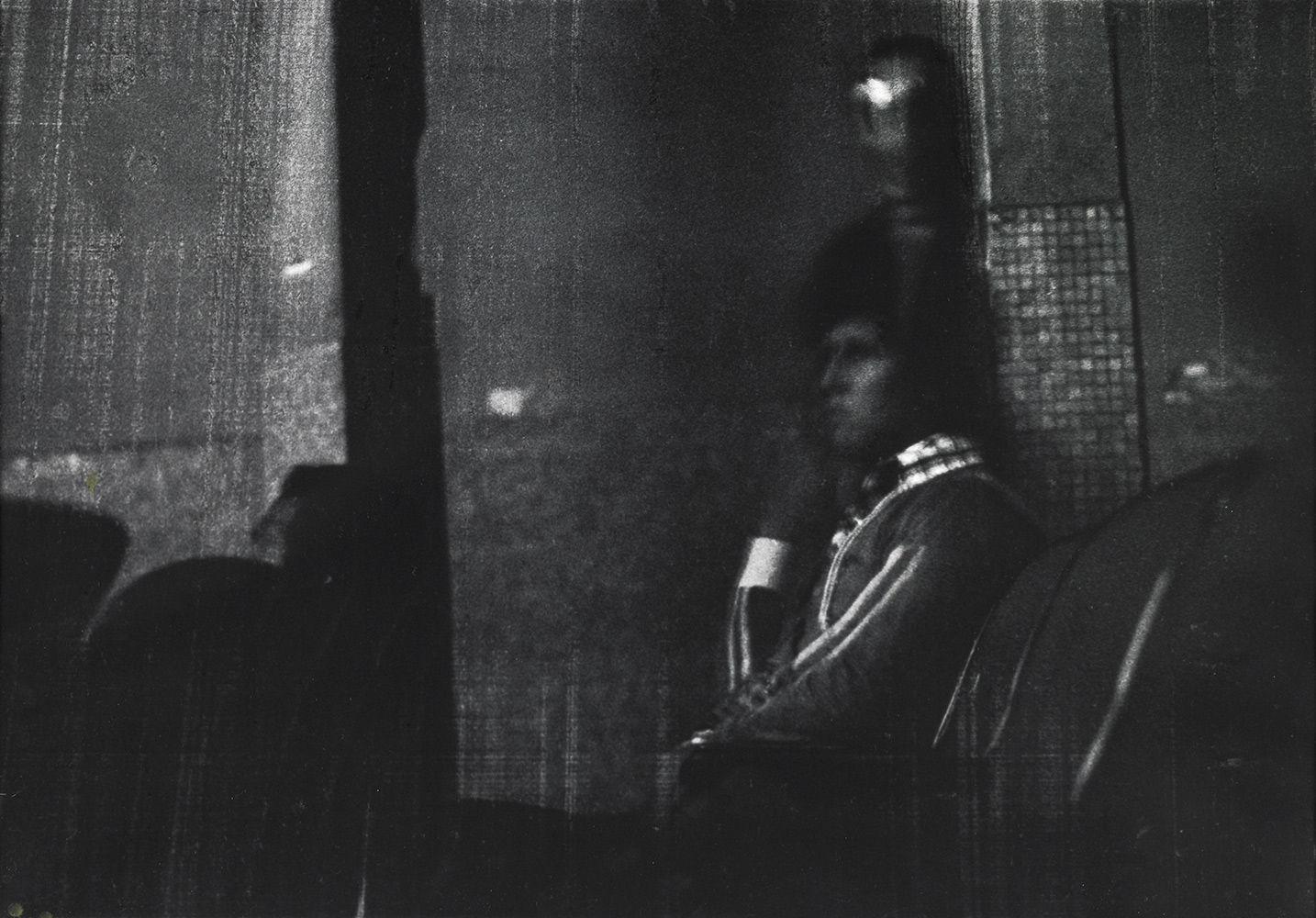

The works in the gallery to the immediate right share the most similarities in terms of their color palette and thematic concept. A quick glance around the gallery reveals an almost exclusively monochromatic suite of photographs, paintings, and readymades. These pieces, which span the 1970s to the present, explore the implications and dangers of being viewed. Rojas’ photo series Sobre Porcelana (1978-2022) and Serie Faenza: Antropofagia en las ciudades (1979) take aim at sexual encounters between gay men in the Mugador and Faenza theaters. Serie Faenza adds complexity to the traditionally voyeuristic dynamic between the viewer and the subjects in these settings. In what is the longest of the artist’s photo series, Rojas observes three men instead of two. The inclusion of a third man adds an uncomfortable tension absent from the artist’s other theater images. This man in a hat acknowledges each vector of observation in the image: he looks at the sexual encounter to his left before pretending not to notice, and in the final image he looks directly at the camera. The implicit or illusory privacy of the viewer is shattered. Elsewhere, Rojas evokes this same form of self-conscious viewership through composition.

The photographs in Sobre Porcelana, including new prints of original negatives never before displayed, are taken through the locks in bathroom doors at the Mogador theater, their backgrounds defined by the striking white porcelain which gives the series its name. The dark borders of the lock form a vignette in each image that reminds us of the tenuous border between the public and the private. The artist’s conceit is to frame each photograph as a window onto a private encounter in a public place, disrupting the stability of any one interpretation in favor of images which simultaneously evoke fascination and unease. This sense of tension, of being caught looking, plays out in adjacent works which look to different mediums as a way to explore these themes further. In the other works in the gallery, Rojas explores deeply personal experiences and fears connected to these theater series.

The large acrylic and ink on canvas, Corte en el Ojo [Cut in the Eye] (1991) is an abstract depiction of Rojas experiencing the consequences of unwanted observation. At the theater Faenza, Rojas tells us through the wall text, someone hit the artist in the eye after realizing he was photographing. This encounter, which left the artist mostly blind in one eye, takes form in Corte, where a dark silhouette that defines the profile of Rojas’ head is punctuated by streaks of white paint. These illuminate the inside of the artist’s head to reveal dark modular forms and a trail of black ink which slithers to the left of the canvas like smoke from a steam engine. Despite the fact that these deft painterly flourishes represent a loss of sight, they continue this gallery of the show’s affinity for works which are concerned with thresholds and with the border between what is occurring outside and inside, even if that border is our very own body.

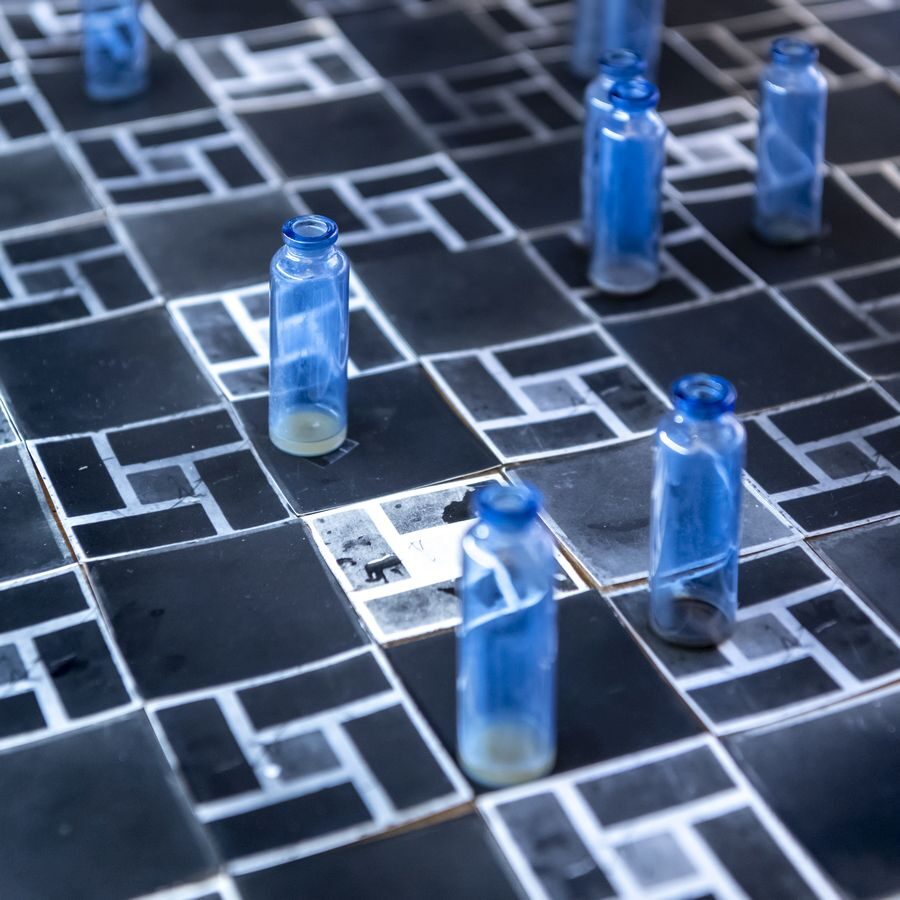

The body becomes palpable in Youth (2022), which sees the artist adding semen to small bottles. These are scattered on top of cut up negatives arranged to look like a tiled floor, a leitmotif in Rojas’ oeuvre since the 1980s. Displayed in a glass vitrine from the artist’s own house, Youth presents viewers with another threshold which they can cross visually but not physically, a statement on the difficulty of being openly gay not just in public, but in private spaces as well.

The remaining galleries in Yo, usted y el Clan are dedicated more to Rojas’ works which deal with extractivism, habitat loss, and the environmental impact of the armed conflict and drug trade. As the viewer walks up the stairs in the central hall, they encounter pieces which home in on the symbolic resonances of the coca leaf and its byproducts, both chemical and political.

The ease with which Rojas switches between and assimilates new visual languages is on full display here, as the upper floor variously displays sewn text on canvas (Nupcias, 2018), taxidermied chicken legs (Bello puerto de mar, 2013), and a series of rings and slate cutouts which recall minimalism and currents of concretist geometric abstraction. Bello puerto () and Cauca (), while superficially unrelated, both look at violent nodes of the armed conflict in Buenaventura and the Cauca region more broadly. Furthermore, both pieces evoke the human hand, through a conceptual appropriation on the one hand, and through geometric abstraction on the other. Ultimately, the abstraction of these works is a form of disfiguration. The bodies and lands of those affected by the conflict become less recognizable by the day, as different now from before as a human hand appears next to a chicken’s.

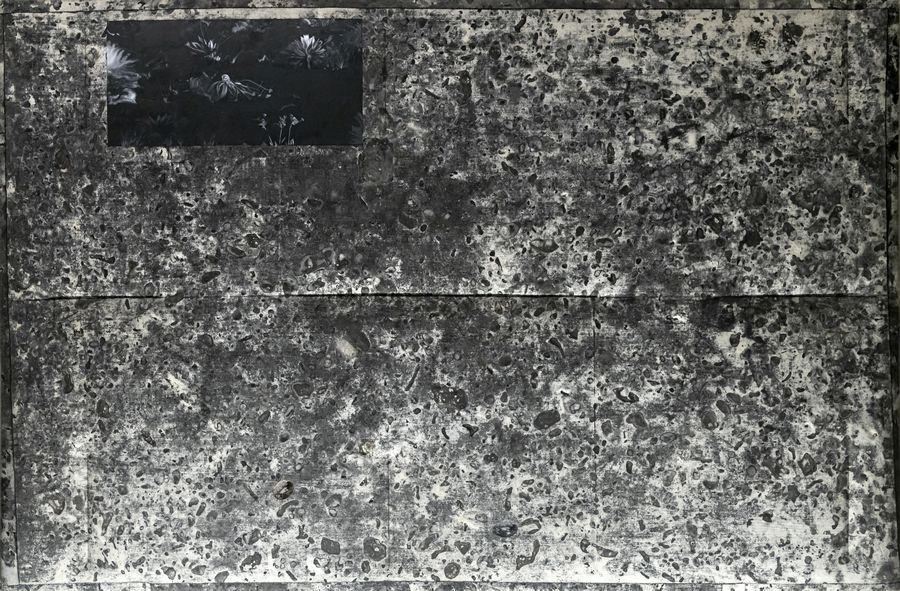

Rojas’ preoccupation with the disfiguration and transformation of bodies continues in the two galleries downstairs. Atrato herido (2022) is a diptyque which deals with the transformation of the Atrato river in Colombia, a body of water which has experienced severe degradation due to (often illegal) gold mining. Working from satellite images of the river, Rojas begins with an imagined view of a “healthy” Atrato on the left and the “injured” Atrato on the right. The healthy Atrato is rendered with pieces of gold, forming a glimmering band which snakes its way down the gridded landscape. The injured Atrato, on the other hand, is a circuitous nest of brown streaks created with mud, a critical look at the kind of “progress” which stops the progression of water itself, damaging the ecosystem for all forms of life. These works adopt the same aesthetic as the large-scale works presented at the MAMBO show. While they don’t overwhelm the viewer in the same way as El nuevo dorado (2021), the Atrato diptyque is a compelling example of a newer visual register for the artist, one which looks to clearly delineate what is being lost as the country marches towards a misguided sense of “progress.”[1]

This march towards progress is linked to the beginning of the conquista and to the Colombian republic in the 19th century with Yugo (2005). Here, an archeological artifact from the Tumaco culture is paired with an architectural ornament in the 19th century republican style. The work, Rojas says, is meant to give an account of the “subjugation of indigenous people to European culture which has been violently imposed since the conquista.”[2] More than just a statement on colonization, Yugo looks at the legacies of mestizaje and the construction of Colombian identity. The superimposition of the Tumaco artifact with an early vision of a Colombian architecture speaks to the positionality of Rojas and of most Colombians: that of a people who are both oppressors and oppressed, colonized and colonizers.

The presence of works such as these in the galleries dealing mainly with land and the environment is key. The show does well to alternate between macroscopic views of environmental degradation such as the Atrato diptyque or the abstract Agua de los Andes canvases (1995) and works which clearly address the rural and indigenous communities disproportionately affected by the loss of these habitats. Despojo [Displacement] (1996) sees the artist place a small stone figure on top of a budar, a ceramic plate used in many indigenous communities. The artist describes the symbolic weight of the plate, saying that it represents the vestiges of the communities displaced by the conflict who are forced to abandon their life and move to cities, often taking up work as marginal laborers.

A few works throughout the show, while individually compelling, are less impactful when placed in dialogue with the works around them. On the second floor, Chicha-Homenaje a Antonio Caro (2022), feels tacked-on. It is linked to the other works almost exclusively through its use of a natural object with explicit regional associations, almost a given at this point with Rojas. While the friendship between these two giants of Colombian art is certainly palpable, the work’s inclusion amounts to little more than a footnote on a floor which otherwise articulates its message with great economy. The late great Colombian artist, and the rest of the works on this floor, perhaps deserved better.

Likewise, En la orilla de la escasez (2014) presents viewers with a dumbed-down version of what Rojas often does so well. While the use of materials such as gold, mud, and coca often add another dimension to the artist’s installations and sculptures, the artist’s photograph of rice and corn in a boat-shaped leaf feels a little too direct. Displayed behind glass, the palpable connection of raw materials to their social consequences, so often a driving force behind Rojas’ best work, is absent.

Ultimately, Yo, usted y el Clan, is a gallery exhibition of tremendous ambition. Bolstered by large gallery spaces and a truly expansive range of works, the team at Casas Reigner has presented a retrospective of almost museum-like scope. For those who visited Rojas’ show at MAMBO last year, Yo, usted y el Clan is unlikely to dazzle, retreading many themes with slight variations. However, these themes and works are fully worth revisiting, as Rojas proves that he is constantly honing his conceptual toolkit. In the hands of the now 76-year-old Colombian artist, the nation’s social and environmental ills are removed and examined with surgical precision.

[1] Much of the gold mined in Colombia is needed for the internal components used in the production of iPhones. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/30/the-weekly/how-tainted-gold-may-have-ended-up-in-your-phone.html

[2] Wall text

También te puede interesar

Bordes de la Cotidianidad.videos de Artistas Colombianos

El Parqueadero, el laboratorio de proyectos artísticos del Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia del Banco de la República – MAMU, en Bogotá, exhibe por estos días "Bordes de la cotidianidad", un proyecto curatorial de...

Leonel Estrada:arte Blando

"La actitud polifacética, cosmopolita y arriesgada de Leonel Estrada se reflejó en la variedad de estilos y técnicas en las que adentró su trabajo como artista. Además de haber sido odontólogo y gestor cultural,...

ANA TOMIMORI: FINCA DE DESCANSO

La artista brasileña Ana Tomimori ha vivido los últimos cinco años en la parte alta de una montaña de la cordillera oriental de los Andes. Allí ha sido caficultora y madre por primera vez....