AGNES PELTON: DESERT TRANSCENDENTALIST

Desert Transcendentalist is the first solo exhibition devoted to Agnes Pelton (1881–1961), a pioneer of American abstraction, in twenty-five years. Consisting of forty-five luminous canvases made between 1917 and 1961, the exhibition is a rare opportunity to experience Pelton’s profoundly spiritual body of work and to confirm her place in art history. Organized by the Phoenix Art Museum, it’s on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art [original dates: March 13 – June 21, 2020].

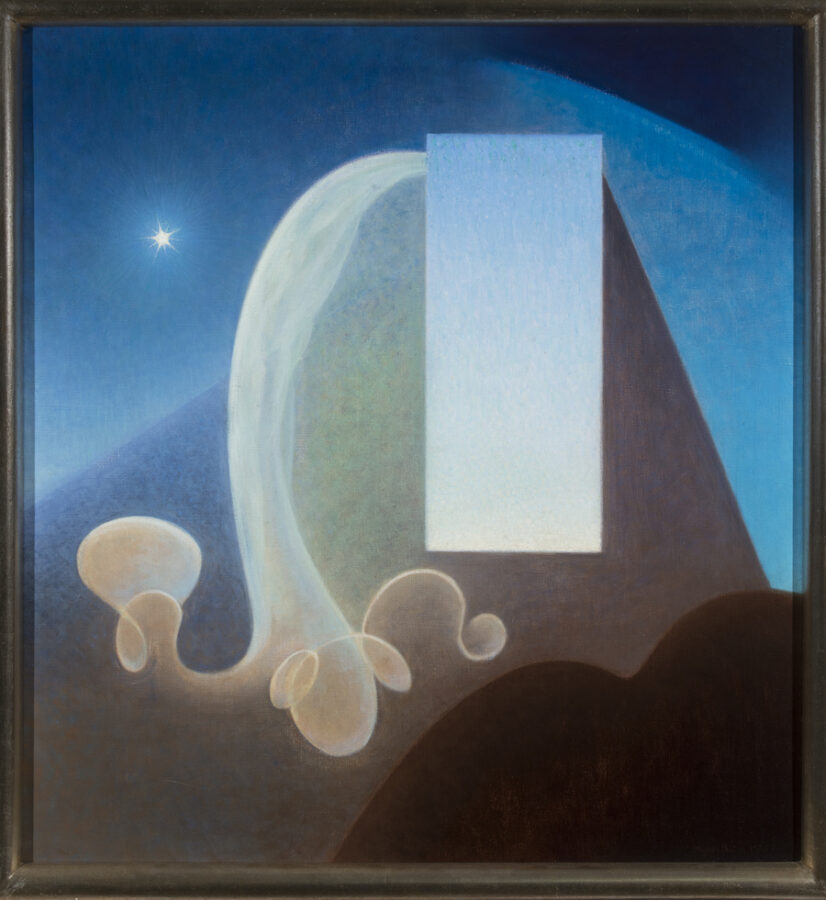

Agnes Pelton strove to portray a spiritual realm beyond material appearances. Her artistic breakthrough came in the mid-1920s in a series of abstract paintings depicting incorporeal subject matter such as air, light, water, and sound. In the decades that followed, as she began to immerse herself in the study of esoteric and occult philosophies, her imagery evolved. She paired the emotive power of ethereal abstract forms with delicate, shimmering veils of color and mystical symbols such as stars, mountains, and fire to represent the union with “Divine Reality” that she experienced in dreams and meditation. She once described her process of meticulously applying thin layers of pigment to create subtle, luminous hues as “painting with a moth’s wing and with music instead of paint.”

Pelton received little critical encouragement for her abstract paintings during her lifetime as a result of living away from the mainstream art world for most of her career, first in the relatively secluded East End of Long Island and later in the Southern California desert. To earn even a modest income, she painted portraits and realistic landscapes that she sold to friends and tourists. Her greatest support came from artists in the short-lived Transcendental Painting Group of New Mexico (active between 1938 and 1941), who shared her belief that abstract art could be a vehicle for transporting viewers to enlightened realms.

Agnes Pelton harnessed abstract forms and shimmering veils of color to portray the spiritual enlightenment she experienced in dreams and meditation. Exposure to Wassily Kandinsky’s book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, in which the Russian abstract painter called upon artists to express their inner, spiritual lives through abstract form, led Pelton to embrace abstraction.

Her depictions in the 1910s of dreamlike, single female figures communing with nature were well received. In the mid-1920s, she turned her attention away from this subject matter to focus on the unseen, spiritual world. Her concurrent move to Water Mill, Long Island, and subsequently to Cathedral City, a small community near Palm Springs, California, isolated her from the mainstream art world, which took little notice of her symbolic abstract paintings. Not until her first retrospective in 1995 did her luminous images of transcendent enlightenment begin to receive their due.

Like Georgia O’Keeffe, a contemporary with whom she is sometimes compared, Pelton studied with Arthur Wesley Dow. Both artists shared an affinity for the landscapes of the Southwest. Pelton painted conventional desert landscapes and portraits to make a living, but she continued to hone her symbolic abstractions throughout her career. It was her abstract studies of earth and light and biomorphic compositions of delicate veils, shimmering stars, and atmospheric horizon lines that would eventually distinguish her body of work. Relatively unknown during her lifetime, Pelton and her work have remained underrepresented within the field of American art until today.

Pelton studied Theosophy, the occult philosophy established in the United States in the late 19th century by Helena Blavatsky, which taught that humans are divine entities who desire to return to their spiritual home in the world beyond the material. Under the influence of both Theosophy and Kandinsky, Pelton modified her motifs, combining occult symbols such as stars, mountains, and fire with a formal vocabulary of curvilinear, geometric forms and layers of delicate color to symbolize the journey from earthly concerns to transcendent reality.

Music played a large role in Pelton’s early life. Her mother ran the Pelton School of Music, and Pelton studied piano throughout her teenage years. The subject matter of Being (1926), Pelton’s first totally original abstraction, is the ineffable ethereality of music and its connection to color, which functioned for Pelton like a «voice» or «vibration,» filling the viewer’s consciousness. Looking back on Being in 1929, she wrote that its dynamism resulted from the «interplay of different color vibrations—colors catching the eye excessively as sequence of sound in music.»

Pelton studied Agni Yoga, a practice based on the idea of fire as a metaphor for the powerful yet dematerialized force that exists within each person and can guide the individual to higher consciousness. Inspired by her study of the discipline, Pelton included fire imagery in a number of her works to symbolize the «Creative fire of the Universe» within herself and others that she expressed in her abstractions. As she noted in her journal, «in the fire world I perceive beauty in the abstract as a living power.»

Concurrent with her investigation of Agni Yoga, stars too began to appear as a key motif in Pelton’s work in the late 1920s, serving as guides to the far-off realm of spiritual enlightenment. Pelton wrote about stars as «messengers,» symbols of «transcendent light, answering through darkness the rising peaks of aspiration.»

The dreams and visions Pelton depicted in her paintings often took the form of narratives that portrayed the journey from the darkness and oppression of the earthly world to the realm of enlightenment. In Ahmi in Egypt (1931), part of the Whitney’s permanent collection, a white swan—a traditional symbol for the female body—proceeds on the blood-red river of life, from the dark chaos of earthly concerns to the divine light of transcendence, as represented by the star in the distance.

For Pelton, water, a frequent motif, symbolized selflessness. Having no shape of its own but instead assuming the shape of its container, it is the archetypal emblem of acquiescence and acceptance. In Sea Change (1931), also a work from the Whitney’s collection, the movement of water serves as a metaphor for spiritual energy and the relinquishing of ego. After moving to California, Pelton derived continued inspiration from the desert’s vast, uncluttered expanse.

Many of the mystics who were central to Pelton’s spiritual development were women, from Theosophy’s founder Madame Blavatsky and her successors, Katherine Tingle and Annie Besant, to Helena Roerich, whose transcriptions of her clairvoyant séances with Blavatsky’s invisible guru Master Morya formed the core of Agni Yoga’s teachings. Pelton copied extensive passages in longhand in her journal of mystic texts, especially the lectures and teachings of Blavatsky. Pelton’s painting Barna Dilae (1935) is a portrait of one of the artist’s female «spirit guides.»

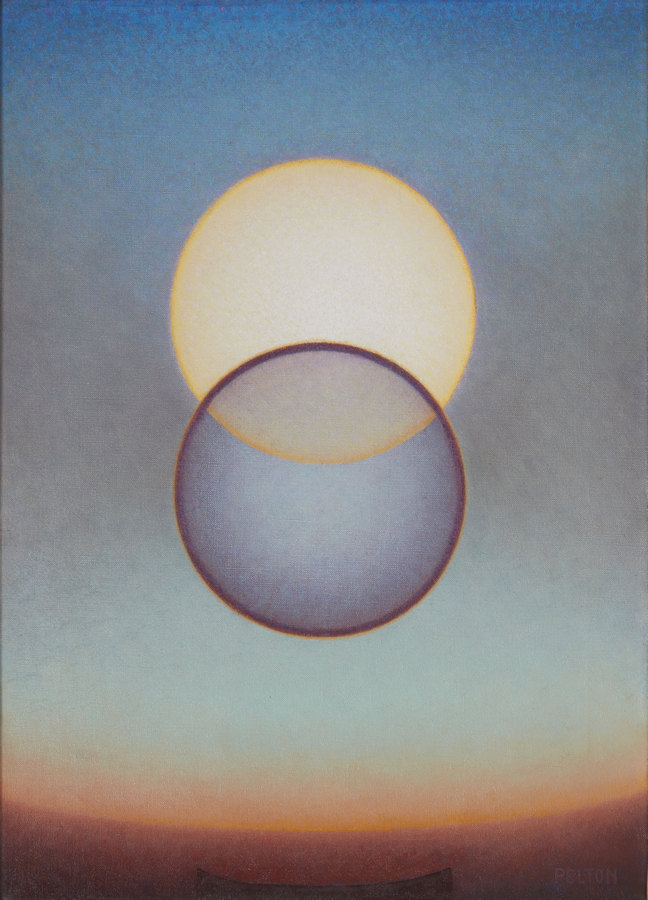

Central to several of Pelton’s late works—Interval (1950), Departure (1952), and Light Center (1960-61)—is the form of the circle, a form with no beginning and no end. It has often been used by artists to suggest infinity and self-contained harmony. Not surprisingly, given Pelton’s belief that art should convey «the interpretation of the higher possibilities of vision,» she often incorporated circles in her compositions, as in Interval, where one appears as a calm radiance at the center of a storm.

Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist offers an important opportunity to experience the work of this previously little-known artist, and to contemplate her efforts to open “windows of illumination” onto the spiritual world.

También te puede interesar

Women Geometers

The exhibition "Women Geometers", organized by the Atchugarry Art Center in association with Piero Atchugarry Gallery summons and celebrates the creations of a significant group of twelve Latin American women pioneers proposing a dialogue...

EL WHITNEY REPOSICIONA EL MODERNISMO ESTADOUNIDENSE

El Whitney Museum of American Art presenta "At the Dawn of aNew Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism", una exhibición con más de 60 obras creadas por más de 45 artistas que resalta la complejidad...

Louis Fratino:come Softly to me

Drawing inspiration from personal experience and, more recently, photographic source material, Louis Fratino makes paintings and drawings of the male body. His work includes portraits, nudes, and intimate scenes of male couples engaged in...