CARIBBEAN FUTURE. CONVERSATION WITH MARÍA ELENA ORTIZ

“Just about nobody thinks of the Caribbean when they think of the future, because they´re likely imagining swaying palm trees and idyllic beaches, rum cocktails, and good vibes…”. Thus announces the text Dancing through the Apocalypse: Considering the Future through the Caribbean´s Past by writer, musician and filmmaker from Barbados, Jason Fitzroy Jeffers. To this, worth to add, the image of the “devastated Caribbean” by the forces of cyclones and hurricanes.

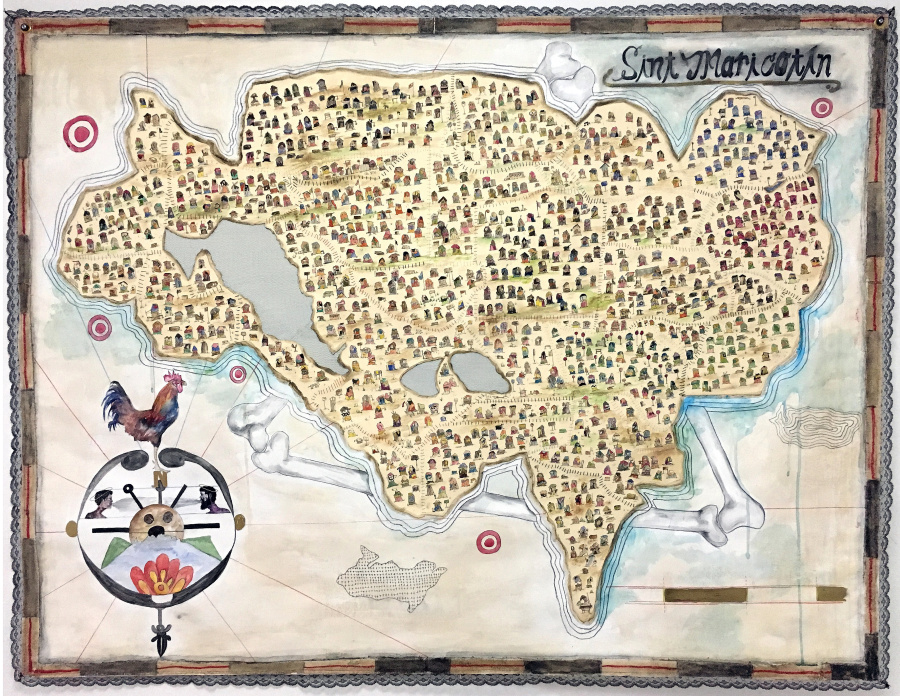

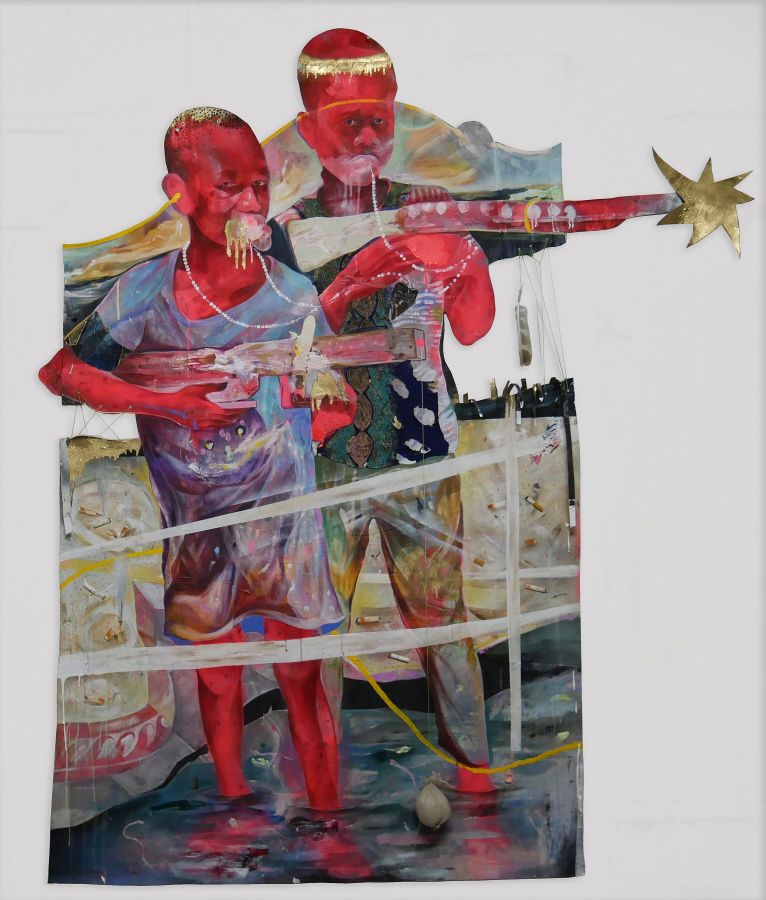

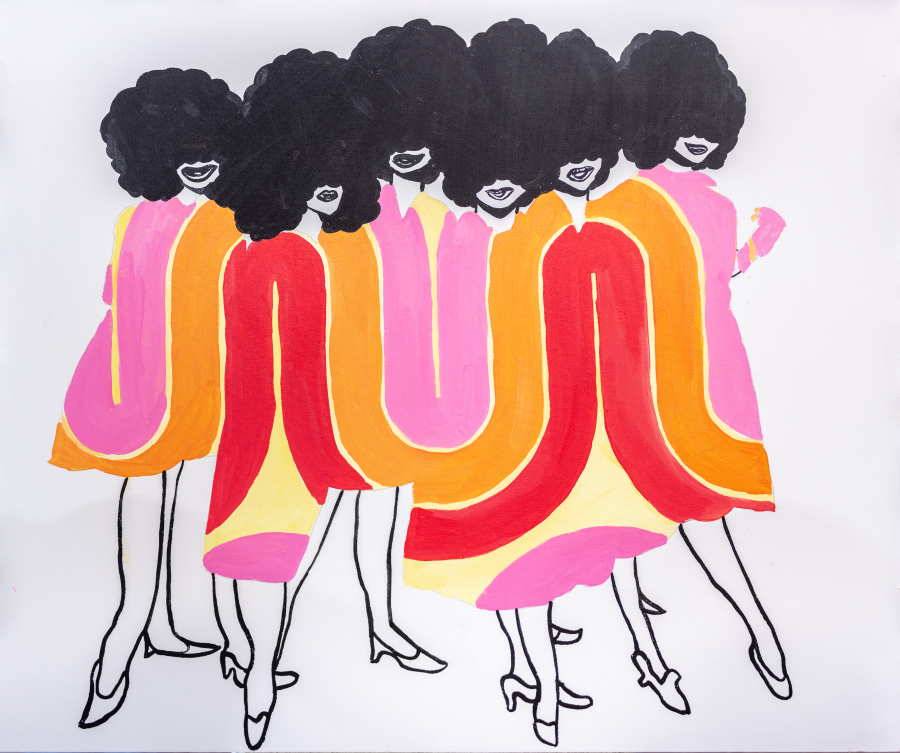

Taking into account the number of Caribbean exhibitions focused on past and present histories, The Other Side of Now: Foresight in Contemporary Caribbean Art curated by María Elena Ortiz and Marsha Pearce at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) approaches the Caribbean as an experiment of possibilities based on time. From the question “what might a Caribbean future look like?” fourteen artists were invited to develop works that challenge the imaginary of exuberance, primitivism, sexuality, tropical paradise and catastrophe, that have defined the region.

In this interview, we talked with María Elena Ortiz (Puerto Rico, 1984) about her curatorial trajectory, visibility platforms, and Caribbean future in the exhibition context.

Aldeide Delgado: The exhibitions At the Crossroads: Critical Film and Video from the Caribbean (2014), VideoIslands (2014), and recently The Other Side of Now: Foresights in Contemporary Caribbean Art, show the development of a research focused on the breaking of a linear and homogeneous definition of the Caribbean. How is this radicalism expressed from your curatorial practice? María Elena Ortiz: I go for what I like, but what I engage with is informed by my non-linear and diverse background as an Afro-Latina born and raised in Puerto Rico—a place that never experienced true post-coloniality. Working in Miami, I have been able to further the discourse of Latin American and Caribbean art in connection to Latinx art and Black art movements, including voices and conversations that have been traditionally excluded. This radicalism is expressed in the themes I am interested for exhibition projects and programs, as well as acquisitions for the museum. I think my radicalism is more evident in my writing style, which often engages a personal narrative. In this sense, I think my curatorial practice engages both a desire to express my point of view and use strategies to further facilitate my discourse, for example using the personal or the trope of a question like in The Other Side of Now. I strive towards the balance between form and content that expresses my authenticity.

AD: Attention to video practices has been an element of interest in your research. In The Other Side of Now, artists like Andrea Chung, Cristina Tufiño and Deborah Jack problematize through this medium the colonial legacy, the state of vulnerability to climate change, and the contradictory notions of abandonment and hope. Could you tell us how audiovisual production has contributed to the critical narration of the problems that dominate the region?

MEO: Artists make visible complex situations that affect the region, creating space for needed conversations. For example, one of the first artworks that had a compelling impact on me was Vela Parking Services (2004) by José “Bubu” Negron, which created a fictitious corporation for homeless people (often heroin addicts) in the Old San Juan in Puerto Rico. On the island, heroin has been a problem that creates impactful everyday images of heroin addiction. I mean… I remember seeing the first time an addict shot heroin when I was driving with my parents to my grandparent’s house. I was not clear about what I was exactly seeing, but it was in the car on a main road, when I saw man sitting under a tree putting needles in his arm. As a form of sustainability, addicts would “watch your car” when you parked in certain neighborhoods. Bubu’s project aimed at officially giving these individuals a job, making visible their role within a social landscape. Also, it made evident the mechanisms of sustainability for drug abuse. Art can represent social problems that are often unaddressed.

AD: Which have been the greatest challenges you have experienced to approach to the Caribbean as a curator and researcher?

MEO: I feel like for anyone interested in doing this type of research, the information is out there. For decades, there have been people working on these subjects. My own research is built on others. So, I do think that it is easy to start locating the key players and start a conversation, especially using the internet. In terms of real challenges, I have had to create a professional space for myself within a landscape that does not include a lot of people that look like me (or you). I feel like that has been my biggest challenge. For example, I have been stopped in different places in Central America and the Caribbean because some people assume I am a prostitute, just because of the color of my skin. To this, you add the “woman factor,” and at times, it can feel challenging, working against the all these stereotypes. However, every time I feel discouraged I talk to my family or put on tropical music Hector Lavoe, Bad Bunny, or Daddy Yankee, and I remind myself that I am “a callejera, street fighter,” jamming to Calle 13.

AD: There are several platforms that contribute to a greater visibility of the Caribbean: CPPC Travel Award for Central America and the Caribbean – which you won in 2014- Caribbean Art Initiative, previously Davidoff Art Initiative, and Tilting Axis, to name a few. How do you assess the state of researches on the Caribbean and its visibility in the region? To what point do the generated structures reproduce or respond to colonizing dynamics?

MEO: I think these initiatives are fantastic. My own research greatly benefited from them, like when I received the CPPC travel grant. We have to understand that in the region alternative spaces and platforms often do the work as the official places of cultural display. This is not the case in all the countries and islands, but certainly an important dynamic to recognize that it is not new to the Caribbean. In 1984, the Havana Biennial was established aiding in bridging cultural production in the region, as well as other spaces in Puerto Rico and Trinidad. That being said, I think that right now, we are experiencing a healthy proliferation of these structures that have enhanced visibility for artists from the region and its diaspora. There is an interest in creating exchanges with Caribbean artists from different regions, bringing together people from the Spanish, English, Dutch and French speaking Caribbean. I do think that we need to focus more on sustainability and history, articulating the art histories that are present in the region, including a diversity of voices—this is an area that we can all work more for.

In many ways these initiatives do reproduce similar colonial dynamics, especially when it comes to funding, each case is different. Generally speaking, I do not think that this is inherently negative. Aside from funding, I think it is important that the professionals leading these platforms are inclusive, engaging in a way that provides autonomy to the Caribbean artists and professionals from the region and its diaspora. I think that is what brings real transformation in thinking.

AD: I consider that PAMM is taking solid steps, in terms of contributing to the investigation of the Caribbean artistic practices. To what extent does the founding of the Latinx Art Fund and the celebration of the Third Horizon and Tout-Monde festivals, in the museum, provide the basis for the establishment of the Caribbean Art Center announced since 2018? What programs will this study center develop to stimulate dialogue with artistic practices in the region?

MEO: At PAMM, we are committed to international and modern art, and because of our context we would like to be the best in presenting Latin America and Caribbean, Latinx, African American and works from the African Diaspora. We, as institution, are committed to reacting to our context, being in conversation. All these programs aim at that and show the interest of our local community and regional partners. The other aspect of these initiatives that is equally important, and not that obvious, is that we are building the fabric of the institutions so that in the future, when we are not working there anymore, others continue with these projects as integral parts of PAMM.

Right now, we are in the process of establishing the Caribbean Art Center. It is a platform that encapsulates all of our Caribbean exhibitions and programming, but also furthers the discourse by initiating new research and enhancing our reach. I don’t want to say much yet about this, because there will be an official announcement soon.

AD: That is great news! Going back to The Other Side of Now: Foresights in Contemporary Caribbean Art; the exhibition assumes as a curatorial proposal the imagination of the Caribbean future. How does this project fit into your research trajectory?

MEO: For me this project is about individual autonomy, which resonates with who I am as a person and curator. On a practical level, the project started with a conversation with Dr. Marsha Pearce in the first Tilting Axis in 2015 in Barbados. So, it developed through the networks of the region. The project also further develops other aspects of my personal thinking. For example, I have engaged in the past with fiction writers for contributions to the catalogue. For this book, we invited YOSS, Rita Indiana, and Aja Monet to participate in the book.

AD: Fourteen artists participate in the exhibition: Deborah Anzinger, Charles Campbell, Andrea Chung, Hulda Guzman, Deborah Jack, Louisa Marajo, Manuel Mathieu, Alicia Milne, Lavar Munroe, Angel Otero, Sheena Rose, Jamilah Sabur, Nyugen Smith and Cristina Tufiño. What theoretical referents and aesthetic categories defined the development of the exhibition and marked the selection of artists and works?

MEO: Marsha and I were interested in a show that challenges a bit the trajectory of Caribbean art exhibitions, which often focus on presenting a pastiche. This is why the project starts with a question. In terms of theory, Edouard Glissant, George Lamming, Kamau Brathwaite, Antonio Benítez Rojo, Beatriz Llenín-Figueroa, marked my thinking. The artist selection was hard, mainly because there are SO MANY great artists. We selected artists that we felt were already working in that vein and others that we wanted to engage with. Of course, we had space limitations. We wanted to have representation from both sides, local and diaspora, especially thinking about the Caribbean as a post-national space. Perhaps this idea is best exemplified in the Hurricane Season of 2017, when the diaspora was clearly influencing aid. This idea of the post-national was also central; we need to acknowledge the role of the diaspora shaping local discourse. I mean, even when we talk about the initiatives in your previous questions, diasporic voices are already present and integral on those projects. Also, I think the 2017 Hurricane Season certainly impacted my thinking towards ideas of autonomy.

AD: From #AfroFuturism, #IndigenoFuturismo, and in this case, I would point to #CaribbeanFuturism, how do you imagine Caribbean societies in the future?

MEO: The Other Side of Now addresses this question, and I hope you come to see the show and read the content of the book, as we hear from others also answering this question. In the future I imagine robust and sustainable art networks and curatorial practices that engage narratives often excluded from what Latin American and Caribbean art has been.

También te puede interesar

Tilting Axis, a Change Agent in The Caribbean

While there is currently a notable international interest in contemporary visual practices from the Caribbean and its diaspora, for Tilting Axis the challenge is to deepen those commitments, so that exchanges with and within...

EN EL HORIZONTE: ARTE CUBANO CONTEMPORÁNEO A PARTIR DE LA COLECCIÓN DE JORGE M. PÉREZ

El Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) presenta por estos días el primer capítulo de "On the Horizon: Contemporary Cuban Art from the Jorge M. Pérez Collection", una exposición multipartita que incluye más de 170...