“HOLES IN MAPS” EXPLORES THEMES OF GLOBALIZATION, MOBILITY AND BORDERS

The reality of paper tears.

Land and water where they are

Are only where they were

When words read «here» and «here»

Before ships happened there.

Now on naked names feet stand,

No geographies in the hand,

And paper reads anciently,

And ships at sea

Turn round and round

All is known, all is found.

Death meets itself everywhere.

Holes in maps look through to nowhere.

Laura Riding, The Map of Places, 1928

By Juliana Steiner, curator

Holes in Maps explores themes of globalization, mobility and borders by examining ways in which personal narrative, social critique, trade, nationalism, identity and citizenship intersect. Like Riding’s poem, the artworks in this show challenge maps certainty and stability, exploring the immense gulf between lines on paper and lived experience – between symbols and their referents. Maps may reveal political and geographical realities, but what do they conceal?

Holes in Maps was born out of a desire to explore the strained relationship between the simple outlines of a map and the complex, emotional, contested human experiences of those boundaries. When one looks at the issues at hand through the lens of postmodern theorists, an analogous dissonance emerges between the world of intellectual discourse and the abrupt limitations of real life. For instance, social theorists Deleuze and Guattari advocate the rhizome as a model of being in which self and identity are not linked to one place or culture alone. Their rhizome endorses rootedness but forswears immobility–what a beautiful idea, and how unevenly attainable.

Maps are created and enforced through power, and disproportionately affect those who have none. One might argue that the opposite of rhizomic thought is the current global trend toward a nationalism that harshly defines and enforces social and national identities and curtails freedom of movement. (We may wish for the freedom to embrace the rhizome, but can we get a visa?) A series of barriers – physical, socioeconomic, and bureaucratic – separates those who are able to embrace “rhizomatic lives” from those who are not. For some, crossing borders has never been easier. For others, attempts to traverse them are repeatedly frustrated by newly erected barriers, while the necessity to transgress them can mean the difference between life and death. Perhaps thoughts cannot yet be confined, but physical access can and is. Through physical interventions and transformative recreations, the artists in Holes in Maps focus our gaze on the negotiation between personal agency and constructed barriers, and remind us to consider their cost.

Sanne Vaassen, FLAGS, 2017-presente. Vista de la exposición Holes in Maps, en 601 Artspace, Nueva York, 2019. Foto cortesía: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

Sanne Vaassen, de la serie FLAGS, 2017-presente; bandera holandesa retejida por Jipke Lezwijn. Vista de la exposición Holes in Maps, en 601 Artspace, Nueva York, 2019. Foto cortesía: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

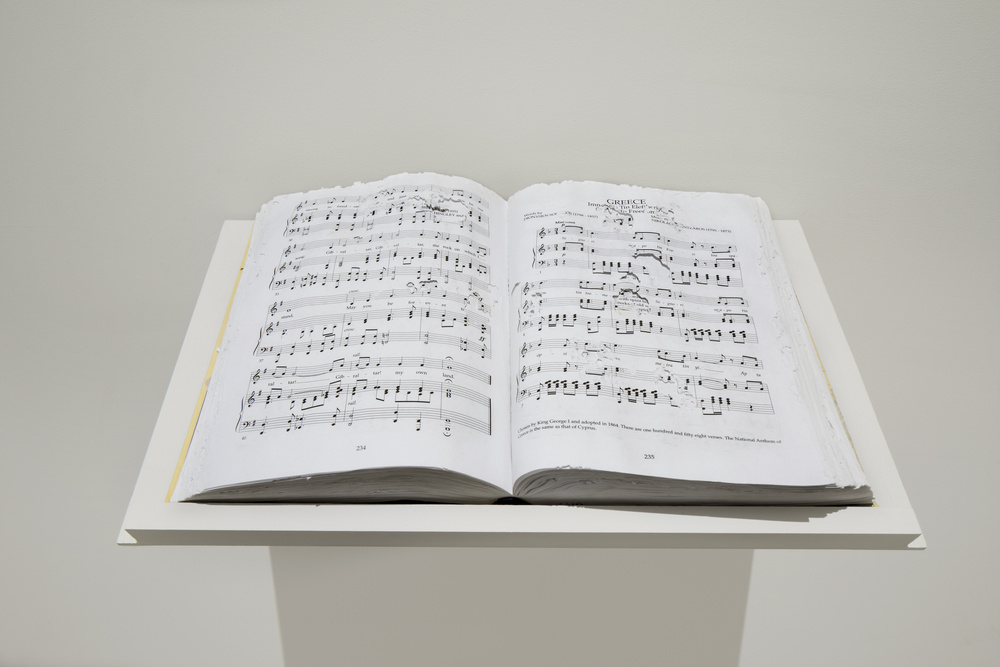

Sanne Vaassen, The National Anthems of the World, 2014. Hard cover book, 9.8” x 7.2’’x 3.7’’. Photo courtesy 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

For her project National Anthems of the World, Dutch artist Sanne Vaassen fed a book containing the scores and lyrics for the national anthems of 198 countries to a group of snails. They slowly ate away notes and words, altering the semantic and material content and challenging the intrinsic authority of the national anthem.

As these solemn, official expressions of each nation’s identity were edited by the random handiwork of snails, boundaries between pages dissolved and new music was invented. When performed by a professional pianist, the music feels altered but still emblematic of the traditional form–a form, it should be noted, that is not always indigenous to the country it symbolizes.

In Vaassen’s ongoing work FLAGS, another sacred symbol is transformed by a conceptual process. In this case, the artist personally unravels a series of flags, reducing them to skeins of loose thread, then commissions a weaver from each flag’s country of origin to re-weave them in any way they wish.

Their only instructions are to use only the thread supplied, and to use all of it. As the flags’ emblematic colors, lines and symbols are woven anew, they become the product of one individual rather than a means to represent an entire nation. With this in mind, Vaassen has endeavored to work with weavers from communities whose voices are frequently excluded from the national conversation. For instance, the Colombian flag was rewoven by a member of the Wayuu tribe, an indigenous community whose language and culture were only officially recognized by the Colombian government in 1991.

Metegol (or Makeagoal) by the Brazilian artist Regina Parra bisects a hand-painted foosball table the artist purchased from the Bolivian migrant community of Sao Paulo. Isolated and poor, members of this community often labor in illegal sweatshops to pay back the smugglers who arranged their passage, and are largely ignored by the rest of Sao Paulo.

Through her volunteer work with an organization supporting migrants, the artist discovered that every Saturday the community gathers to play foosball on handcrafted tables made in Bolivia. The tables reflect both their own language and teams as well as a growing transfer of loyalties to Brazilian teams.

The game Parra has chosen to hijack with a wall is a match between popular Paulista team Corinthians and international powerhouse Barcelona. Bolivians may root for a Paulista team, but access to mainstream Sao Paulo society remains almost impossible. In other words, while football, and its proxy foosball, could easily be considered a unifying passion throughout Latin America, it’s popularity doesn’t supersede prejudices and divisions.

Vista de la exposición Holes in Maps, en 601 Artspace, Nueva York, 2019. Foto cortesía: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

Adriana Martínez, Tutti Frutti Market, 2018, frutas plásticas, adhesivos, seis cajas de plástico, madera, malla. Vista de la exposición Holes in Maps, en 601 Artspace, Nueva York, 2019. Foto cortesía: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

Adriana Martínez, Tutti Frutti Market, 2018, frutas plásticas, adhesivos, seis cajas de plástico, madera, malla. Vista de la exposición Holes in Maps, en 601 Artspace, Nueva York, 2019. Foto cortesía: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

Adriana Martínez, Al Final del Arco Iris, 2015. Currencies of Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Chile and Brazil, rubber band, 3” x 3’. Vista de la exposición Holes in Maps, en 601 Artspace, Nueva York, 2019. Foto cortesía: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

Tutti Frutti Market by the Colombian artist Adriana Martínez is a reproduction of a Colombian roadside fruit stand, traditionally made of wood and other found materials. Martinez’s stand is filled with plastic versions of fruits, such as bananas exported from Colombia, as well as exports from other parts of the world. The shiny plastic fruits are almost completely covered with colorful stickers from international corporations that import and export, like Chiquita Brands International, Golden Mangos and Fruta Ponche Valencia.

Over 85% of the bananas, avocados and mangos consumed in the USA are imported, most of it from countries whose relationships with the US government range from problematic to antagonistic. (Trump’s pejorative descriptions of Mexicans and Hondurans and his attacks on the Chinese come to mind.) Martinez’s work points to the interesting paradox of borders: people can be banned with the same determination with which desired fruits (and other goods) are welcomed. Tutti Frutti Market reminds us of the crucial role that corporate intercessors play in these fruits’ cross-continental travels. Their stickers mimic the coveted “approved” stamp of a customs agent, recalling the thousands of visas that are denied every day to Latin Americans and countless others.

Al final del arco iris (At the End of the Rainbow,) also by Martínez, consists of a carefully organized rainbow bundle of paper currency from various countries in Latin America and the Caribbean: Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Chile and Brazil. Martínez and friends collected freshly printed bills whenever and wherever they could for over two years. By organizing the bills by color, rather than worth, Martínez momentarily shifts our attention to the bills’ aesthetic properties rather than their economic ones, as she simultaneously relocates them into the financial value system of the art world.

The Brazilian Real, product of one of the strongest economies in Latin America, holds equal space with the Venezuela Bolívar, which has undergone one of the worst devaluations in economic history: a dramatic representation of how the economy of the art world is disconnected from the economic reality of the populations that use these currencies. This piece has already been sold for far more than the value of the bills themselves.

Museum Mixtapes by the Colombian artist Juan Obando both critiques and momentarily interrupts the historical exclusion of certain social groups from public cultural spaces like museums. Obando invited a group of rappers living in the Southeast United States to visit established museums in their areas and freestyle about the artwork exhibited, paying no heed to the wall text. He filmed their commentary and created a 22-minute video of freestyle rhymes. Inevitably the hip-hop narratives clash with the museums’ “official” curatorial narratives.

By inviting these artists to rap in these spaces, both the performance and the environment are shifted into new contexts, addressing the role class and race play in access and ownership of cultural space. Obando highlights the lack of representation of brown and black individuals in the art historical canon, and the way in which coded “art language” -and in some cases, contemporary art itself- can be off-putting and incomprehensible to all but a small group of people.

Reynier Leyva Novo, Eternamente te esperaré, 2015, video, telescopio, 10:06 min. Vista de la exposición Holes in Maps, en 601 Artspace, Nueva York, 2019. Foto cortesía: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

Eternamente te esperaré (I’ll Forever Wait for You) is a response by the Cuban artist Reynier Leyva Novo to the dangerous journeys undertaken by thousands of Cuban migrants who illegally cross the Caribbean Sea on their way to Florida. In 2015, one in four people who crossed this maritime border lost their lives. This same year, Novo spotted a makeshift sailboat in the Caribbean Sea. Through the lens of a telescope, he videotaped the boat drifting somewhere between the island and the peninsula, its sail inscribed with the words “Eternamente te esperaré” which translates to “I’ll Forever Wait for You.”

The piece was originally exhibited in 2015 at El Apartamento in Havana, Cuba. The gallery was left empty save for a telescope focused on the boat floating in the sea beyond The Malecon, Havana’s harbor. For its first showing since then, the artist has reinterpreted this work for 601Artspace by creating a video installation viewed through a telescope. The fates of the boat and the author of these words are unknown, and perhaps the video documentation is all that remains.

Bittersweet, by the Croatian artist Matej Knezevic, explores Croatia’s strained relationship to its past as part of Yugoslavia, and to its present as a part of the European Union, but outside the Schengen Treaty, meaning they use their own currency rather than the Euro. Bittersweet uses a well-known brand of local cookies to create a giant Euro coin and a giant Kuna, Croatia’s currency.

Viewers are neither invited nor discouraged from eating the work, but permission is granted by the staff if asked. The work changes over the course of the exhibition, mirroring the mobility and variability of the EU’s currencies and their responsiveness to changing politics, supply and demand, and the fluctuation of other currencies. Inspired by the European debt crisis of 2006, this work also recalls the fairy tale Hansel and Gretel, where a brother and a sister get lost in a forest and are lured inside a house made of cookies.

Alia Farid, Theater of Operations (The Gulf war seen from Puerto Rico), 2017, grabaciones encontradas, audio, 3:53 min. Vista de la exposición Holes in Maps, en 601 Artspace, Nueva York, 2019. Foto cortesía: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

The Vietnam war might have been the first war to be televised, but it was two decades later during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 that a war was first covered in real time, worldwide, changing the way news and television would be consumed by society.

Theatre of Operations (or the Gulf War seen from Puerto Rico) by Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican artist Alia Farid is a 3-hour compilation of videotaped VHS news footage recorded by the artist’s grandmother. The viewer follows Farid’s family’s journey through news reports as they flee from the Gulf to the Caribbean and become part of a sensationalized media spectacle that includes invasive personal interviews and dramatic TV specials.

Farid’s Theater of Operations is divided into three parts, which take their titles from Jean Baudrillard’s series of short essays about the Gulf war. Part 1 is titled, The Gulf War will not take place; Part 2, The Gulf War is not really taking place; and Part 3, The Gulf War did not take place.

As the story unfolds through the Puerto Rican news media, the story of Farid’s family segues into a questioning of the island’s role in the war, during which 2,500 Puerto Rican soldiers were deployed as part of the US military. As the piece unfolds, the narrative encompasses an exploration of U.S. interference and territorial invasions and the uneven power dynamics between Puerto Rico, Kuwait and the United States.

HOLES IN MAPS

Curated by Juliana Steiner

Matej Knezevic

Adriana Martínez

Reynier Leyva Novo

Juan Obando

Regina Parra

Sanne Vaassen

601 Artspace, 88 Eldridge St., New York

Until February 17, 2019

Featured image: View of the exhibition Holes in Maps, 601 Artspace, New York, 2019. Photo courtesy: 601 Artspace /Marie Guex

También te puede interesar

Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the uprisings, "Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989" is a long-awaited and groundbreaking survey that features over 200 works of art and related visual materials exploring the impact of the...

CRISTIÁN SALINEROS: THERE WERE NO LIMITS BEFORE THIS, ONLY TIME

Salineros works literally and symbolically with abjection: he uses the corpse or feces of migratory birds to invoke a series of borders—both physical and virtual—which are transgressed by the effect of time.

TISHAN HSU: LIQUID CIRCUIT

In the mid-1980s Tishan Hsu (b. 1951, Boston) began a series of works that considered the implications of the accelerated use of technology and artificial intelligence and their impact on the body and human...