COLLECTING IN TIMES OF CRISIS

Today’s art world naturally pays most attention to artists, artworks, and exhibitions. However, a driving force behind the machinery are collectors. Independently from art schools, economic pressure, or governmental funding schemes, they contribute to the production and flow of art by directly supporting artists, sponsoring institutions, and participating in the secondary market. During the course of art fairs, collectors often gather to exchange ideas and reflect on their roles in this ecosystem. Such conversations, inherently intimate, range from one’s individual passion for art, one’s collecting history, or simply personal taste.

However, structural issues around the complex relationship between producers and consumers of art are often left untouched, while it is true that sometimes the intentions of collectors and artists go in the opposite direction. As a response to and critique of society, some artworks are very critical (in every sense of the word) to specific political or economic practices, or to the art market in general, and therefore directed openly against collectors who engage in certain industries.

The reproach of big institutions, for instance, the Whitney Museum of American Art, where artists demanded a board member step down because they sell tear gas, is a case in point. In other instances, it is artists who are criticized for how they produce and market artworks on current topics. This we have seen recently with a Chilean contribution to the Spanish art fair ARCO in which a male artist appropriates a feminist performance for a piece to be sold for several thousands of dollars to benefit his own and his gallery’s pocket. For patronage to be productive, such difficult discussions are necessary because they address how we engage and deal with underlying societal issues, but differences can never be entirely flattened out.

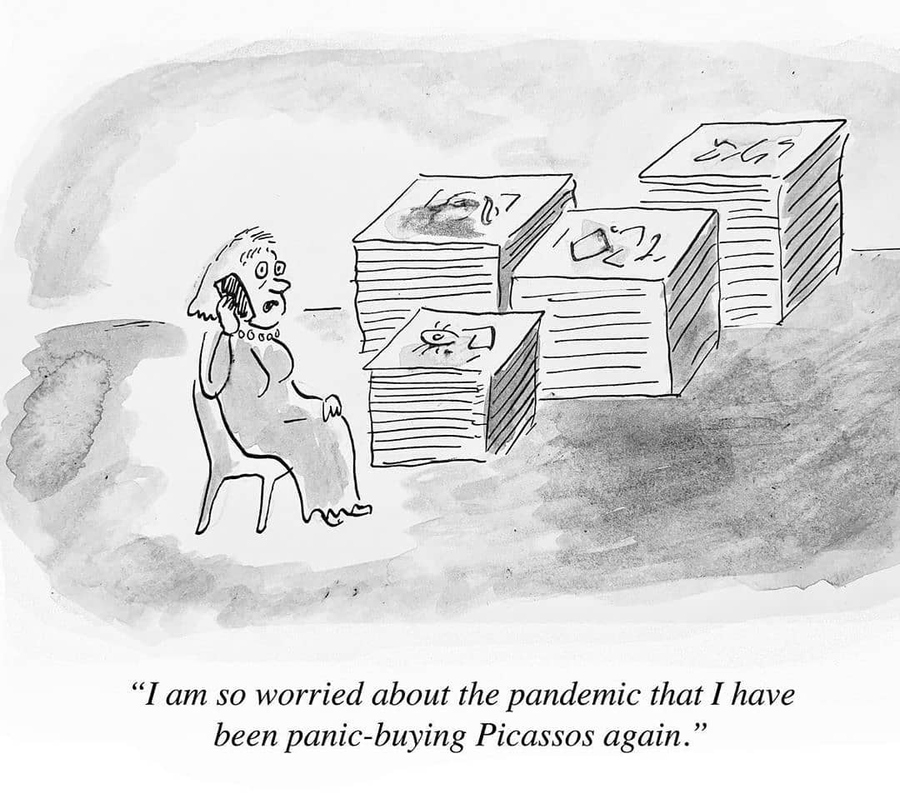

In times of crisis, contradictions become more acute, or arise from the very context. The production of artworks takes on a different dynamic, new topics appear, the conversation between artists and collectors may change, as does the approach to acquiring art. In my opinion, collecting always is political, it requires responsibility and conviction. It needs a certain vision, as well as flexibility. It is therefore crucial to look at the individual situation and how collecting strategies have to adapt to it.

In the case of the Estallido, the outbreak of social unrest in Chile in October 2019, we see clearly pronounced demands from protesters: Public access to water, higher minimum wages, better access to education, and gender parity, to name but a few. Many of the artworks deal with these problems, demands, and how they came into existence. Many of the artworks also deal specifically with how certain actors in this crisis proceed—protesters, politicians, institutions like the police—and the results of their actions. The most visible issue in this case are undoubtedly the human rights violations that have occurred continuously since the first day of the crisis. Above all, however, is the demand to reduce social inequality. It is the disparity of people with extremely large incomes and people struggling to survive. This condition also concerns the relationship of artists with the art market, which is not the most pressing of issues, but nevertheless becomes all the more visible in the current crisis.

As many artists take an explicit stance in the discussion, it is urgent to reflect on how their artworks function in comparison to the existing parameters and infrastructure. When the usual exhibition cycles are suspended, artists struggle to work, and the whole market in its daily routine stops, established mechanisms fail, even become questionable in their ethics. Yet, it is also when a lot of art is created and becomes relevant in the everyday of the crisis. Art’s genres and status become diffuse; from objects to performances to memes and recycled memes, it can be everything. Undeniably, the art scene changes, and therefore our position in it. Hence, what is the role of a collector in this time?

This question might be infinitely intellectualized, but it is possible to boil it down to a few basic thoughts about how a collector may actively participate in the new dynamic and confront inherent contradictions. Collecting art during a crisis and art about the crisis can be a delicate gesture and deserves additional deliberation, which is why I would like to offer some reflections on collecting under exceptional circumstances:

Consider art more as a practice than an object. A bunch of tear gas bombs do not form an independent aesthetic work to be contemplated in silence. They were collected from the streets where protesters and police violently clashed, they call out the hostile attitude of the state toward its citizens and are proof of how protesters work together to gather this material. Another example: a photograph of the protest does not just follow Renaissance composition principles, it says the photographer was there on the ground to testify injustice and often to join the protesters in voicing their discontent with the government. The artwork becomes the protest, an active element in the conflict, which cannot be measured in centimeters and paid in dollars. What becomes crucial is to incite a change based on the political discussion, not to find a mute representation for it.

Artworks do not always lend themselves to financial investments. In the first place, they are unique objects of an irreproducible moment. This might suggest an increase in value over time, but as historical objects, they primarily serve to remember the past. Appreciating this as a value on its own over monetary potential makes a collection more meaningful and lasting.

Take your time in buying art and also give the whole process time to mature. The crisis has already given birth to many artworks, but many more are in the making. Spontaneous productions can be excellent expressions of the feeling of the moment, or lack profundity of thought for the same reason. Ultimately, we can only judge in retrospect. Moreover, the social unrest is not over, and time will allow us to digest what we have experienced in the past months and think through the consequences.

Follow an artist you like beyond the duration of the show or the crisis. Acquaint yourself with the artist’s career and how they have dealt with socio-political topics before and then evaluate whether the artist considers the crisis as a one-off chance to make something unique, instead of a continuing interrogation and practice. The work of an artist already committed to social issues will certainly make a stronger argument than a quickly assembled interpretation of symbols.

Think about the context of where you see the artwork, whether it is in the street, in an artist’s studio, or in a gallery. You may for several reasons not be able to experience the protests directly, but it is helpful to be aware of what is happening and what exactly the artist references in their work. If the work was made in the street to be seen in the street, it might not be as powerful in a white cube gallery.

It is probable that artists whose works you already collect temporarily stop working and exhibiting as usual. They might be actively involved in the protest, join cabildos, or fulfill other civic duties. Everyone will have to reorganize their life according to the new, difficult situation, losing jobs and therefore finding less time for art. This is not a break in their practice, but a momentary hiatus or an interesting turning point. Given the economic precarity of many artists and the fragility of the local art scene, collectors can be a corrective to the downturns, as explained in the following point:

Support artists on a sustainable level, not object-based. Helpful ways to do so are paying their studio rent, buying them materials, paying them allowances, financing trips, residencies, exhibitions, and further education. The sale of artworks is too volatile and sporadic as to allow an artist to meet essential recurring needs like food, rent, and health care. And with more financial insecurity comes less time and energy to make art. Therefore, think independently from material, measurable output and think of art, as said in the beginning, as a practice, in which it is important that you participate. (This is equally important in other types of crises, such as the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic).

But most importantly: Acknowledge that you yourself are part of the current situation. The protest is not visible in every corner of the country, but as a whole, we are all in this together. As a collector, you are more likely than others to have a comfortable position in life with time and funds to collect art. Through your social status and profession, you are a role model to others and influence their lives directly, for example as an employer. If you are an adult and registered, you are able to vote in elections and therefore take part in forming our society.

There is a good chance that some demands of the protesters oppose your personal opinions and lifestyle, which is the biggest contradiction of collecting in times of a crisis. Yet, it is a remarkable feature that the protests in Chile started without a partisan mentality: it was not about right wing or leftist politics, it was about clear demands that went beyond party agendas. In this sense, it is less about who than what you vote for, about what personal convictions you have.

The artworks alluded to here are, qua being art, not a one-sided isolated political statement, but a call to conversation. They are a meeting point to address potential contradictions between protesters, artists, and collectors. They invite us to reconsider our interests in the crisis but also in the everyday, and show us what responsibilities we have as individuals. This is an opportunity for us to question our behavior and change our opinions. This is the only and the most precious thing art can do, and it excludes no one from the discussion. And collectors, once again, are welcome to participate in the process with their passion and commitment.

También te puede interesar

Lo sentimos, no pudimos encontrar ningún post. Por favor ensaye una búsqueda diferente