EDGAR CALEL: B’ALAB’ÄJ (JAGUAR STONE) [PIEDRA DEL JAGUAR]

In 2022, Maya Kaqchikel Guatemalan artist Edgar Calel painted an oil canvas of roughly forty by thirty inches in which a foregrounded fragment of earth can be seen. In some places brown, in others black, the soil is surrounded by an imperfect circle of rocks of different sizes, atop of which a red candle burns. The Spanish translation of its title reads: Lugar donde las rodillas se doblan [The place where the knees bend]—or Xukulb’el, in the Kaqchikel language.

In 2023, the germ of this work grew into a large, irregular mound of real earth spread over an area of 281 square meters to give shape to B’alab’äj (Jaguar Stone). The installation comprises Calel’s first solo exhibition outside Guatemala, on view from July 5 to August 4, 2023, at SculptureCenter, New York.

With an academic background in plastic arts, Calel has developed a practice that spans many disciplines, including painting, drawing, installation, and performance. He constantly explores the tension between Maya Kaqchikel ontology and Guatemalan identity, negotiating sharp critical thinking as part of his role as an artist amid the complexities of today’s contemporary art field.

His presence on the international scene is growing exponentially (Berlin Biennial 2020: Carnegie International, 2022; Gwangju Biennial, 2023; Liverpool Biennial, 2023; São Paulo Biennial, 2023), in step with the Global North’s growing interest in Indigenous artists.

This tendency increasingly pushes Indigenous artists’ works into ritual and distant, ancestral categories, which, in turn, demand—time and again—that Indigenous communities be emissaries for a redemptive future to save us all from the already undeniable debacle of the so-called Anthropocene—a new epoch to describe the current environmental consequences of humankind, including the ongoing effects of colonial genocide and looting on the American continent.

It seems that Indigenous Peoples, with their myriad identities and particular demands, are required to share knowledge—always ancestral—that offers solutions to imposed problems. This dangerously recurring appeal to wisdom from the past—or, conversely but similarly, to the “imagining of new worlds” in the future—evades the responsibility to face the present and avoids replacing the highly positivist need for “certainty” with a non-extractive exercise in listening.

Calel’s work escapes from such a simplistic anthropological reading and points out the nuances of our complex present. B’alab’äj (Jaguar Stone) challenges Western notions of territory: this is not a landscape external to the artist but one of which he is a constitutive part. “The landscape that inhabits me,” as the Bolivian sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui would put it.

For Calel, that ontological landscape is Chi Xot, whose name translates to “on the shores of the Comal or the fire.” This town of more than 40,000 inhabitants sits in the department of Chimaltenango, in the highlands of midwestern Guatemala, which under force of colonial Spanish rule is known as San Juan Comalapa.

“Where is my culture when I’m not in that place?” the artist wonders. “It remains in the body, traversed by what we experience, and remains in the memory, where we transform culture and reproduce it” (“Conversation with Édgar Calel,” C&América Latina, 2020).

For the Qom, who inhabit the current provinces of Chaco, Formosa, and Santa Fe in Argentina, certain components of the person and the body can become detached from the limits of the body’s contour. These deterritorialized extensions—like blood or saliva—exist outside the body but still contain the person.

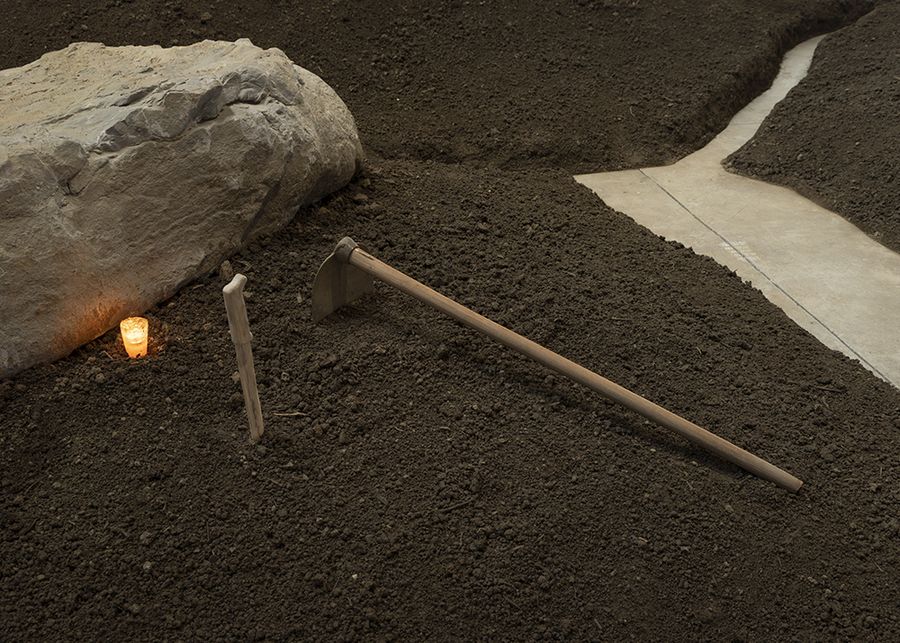

In B’alab’äj (Jaguar Stone), this form of deterritorialization operates in the very materiality of the installation, which becomes a condition of possibility and a sign of the totality of human and non-human. For this exhibition, Calel meticulously organizes the space to explore the expansive power of its elements, which gain strength in sculpture as an expressive medium: earth, rocks, and fire build a channel of communication, a portal that intersects the multiple realities that constitute our existence.

In the main gallery of SculptureCenter, the materiality of the work unfolds in a monumental way, yet it is simultaneously powerfully intimate. The circular pilgrimage that the work proposes is accompanied by a recording that embodies the soundscape of Chi Xot and in this way holds the memory. The words “kit-kit”, which the artist has carved like rivers into the irregular perimeter of the earth mound, evoke the sound his grandmother made “to invoke the spirit of the birds, to feed them with corn seeds” (“Interação com el Guatemalan artist Edgar Calel,” Zine Zona da Mata, 2016).

This recitation of “kit-kit” appears throughout Calel’s work, most often written in the artist’s own hand: for the first time as a mural painted with mud; in his studio and house in Chi Xot; in the window of Galería Trama (Brazil, 2014); embroidered on a tablecloth (University of Memphis, 2020); and on a canvas in his gallery Proyecto Ultravioleta (Guatemala City, 2021).

The installation is completed with a group of work tools: wooden-handled hoes and machetes hang on a white wall in a small adjoining room. “They are resting,” says the artist and laughs.

Humor, as it were, is an unexplored reading of Calel’s work, which has aspects reminiscent of the uncomfortably ironic tone of the performances of the “public secret society” New Red Order (currently on view in the group exhibition Indian Theater, curated by Candice Hopkins, at the Hessel Museum, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York).

However, more often than not, his work is subject to animist and perspectivist explanations that justify non-Western ontologies while often essentializing them. The tools are resting from the productive cycle of planting corn and other crops in the Chi Xot area, an activity central to the continuation of life and one that involves all the members of any given family, including Calel’s own.

A question that B’alab’äj (Jaguar Stone) raises, and that is present in many of the artist’s works, could be formulated as follows: How much of the experience of one land can reach another? Translation, movement, and communication are constants in Calel’s work, and in this installation they manage to unfold, favored by the materiality of sculpture.

By recovering collective processes of meaning-making linked to the place of belonging, the exhibition calls for the persistence of a present that reverses the neoliberal logic of economic concentration and hyper-individualism. Instead, it offers the possibility of thinking about that shared place where one listens to what cannot be seen with the eyes.

También te puede interesar

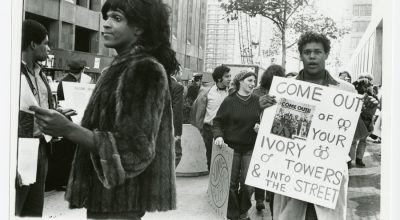

Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the uprisings, "Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989" is a long-awaited and groundbreaking survey that features over 200 works of art and related visual materials exploring the impact of the...

ECOLOGIES OF CARE

"Ecologies of Care" showcases a series of new works created during Ani Liu’s postpartum period, in contemplation of the labor of mothering. Reflecting the material culture of infant and childcare, the works shown are...

JJAGƗYƗ: AIR OF LIFE

The exhibition explores the profound impact of colonialism, particularly through the history of boarding schools established by the Capuchin Missions in the region. This colonial legacy has led to the decline of Indigenous languages,...