THE PARADOXICAL INTERNATIONALIZATION OF “PROVINCIAL ART”. BEATRIZ GONZÁLEZ: A RETROSPECTIVE

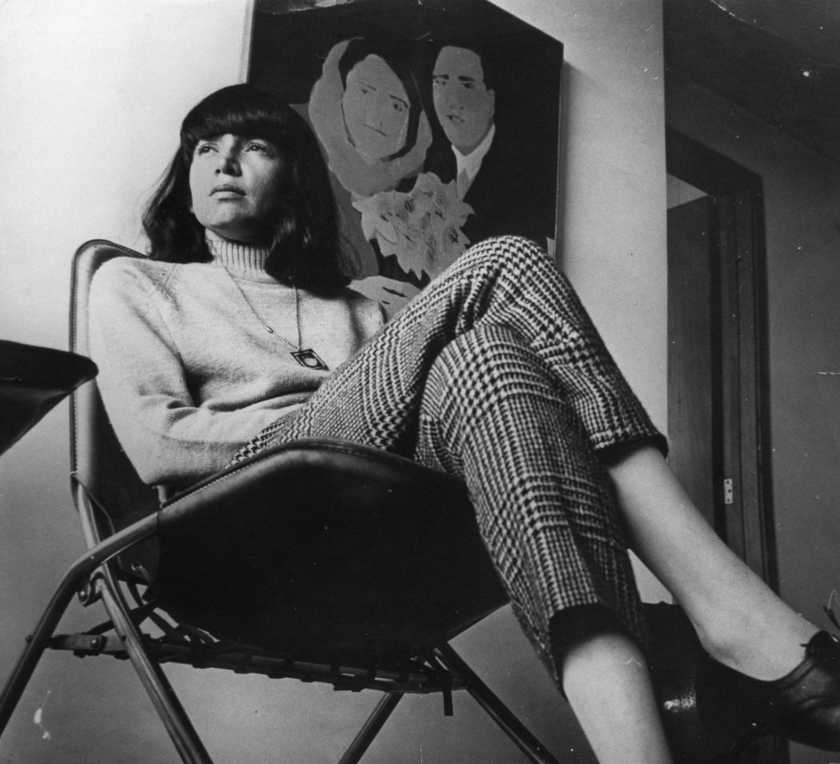

In the mid-1960s, shortly after receiving a Special Mention at the 17th National Salon of Colombian Artists in Bogotá—at the time, a contested site for exhibiting young local artists— a delighted 33-year-old Beatriz González told art critic Marta Traba: “I feel like the forerunner of a Colombian art—even more so of a provincial art that cannot circulate universally except perhaps as a curiosity.”[1] Sixty years later—with works dispersed throughout collections not only in Colombia but also in the United States and Europe— two succeeding retrospectives have turned the attention of the international art world towards González’s prominent career.

The first one, curated by María Inés Rodríguez, toured in 2018 with exhibitions at the CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, and the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. The second one, Beatriz González: A Retrospective, curated by Tobias Ostrander and Mari Carmen Ramírez, opened in October 2020 at the Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia in Bogotá, after shows at the Perez Art Museum in Miami and The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. The exhibition, which covers six decades of artistic production including works from González’s personal collection, reflects the artist’s practice of appropriating images from Colombia’s popular visual culture—a strategy with which she parodies and resists artistic internationalism questioning official cultural and political discourses.[2]

Seen side by side Los Archivos de Beatriz González, a display of the artist’s personal papers curated for audiences in Bogota, provides a unique opportunity not only to understand González’s work under multiple perspectives but also understand how González’s career and works embody a dialogue, at times contradictory others complementary, between the global art world—still dominated by Euro American tenets of modernism— and local art histories.

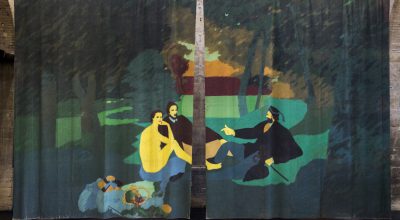

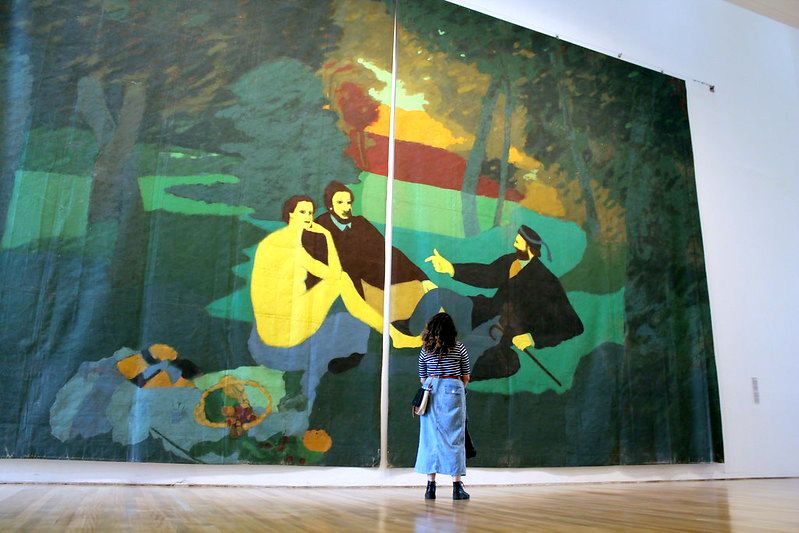

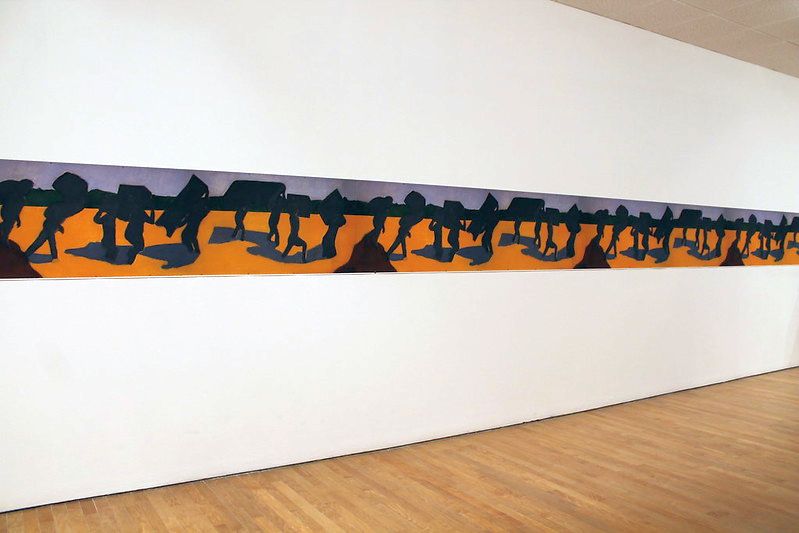

At Bogota’s MAMU, two of González’s largest works introduce the viewer to the exhibition, setting the tone of the retrospective. Hanging opposite the temporary exhibitions gallery’s entrance on the museum’s second floor stands Telón de la móvil y cambiante naturaleza (Backdrop of a Mobile and Changing Nature, 1978), welcoming viewers from the onset into González’s formal and historiographic inquiries on the power dynamics of the international art world. Based on an image of Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’herbe—taken from a reproduction of the master painting in a loose print found in a neighborhood store in Bogota— it depicts Manet’s figures in the characteristic González style: the shapes flattened, employing a strong contrasting palette of bright greens and opaque yellows, and painted with deliberately brusque strokes suggesting the wear of the painting’s auratic qualities, reproduction after reproduction. Painted on a canvas cut in half to simulate the entrance of a circus tent for the 1978 Venice Biennale, it hints, as Ostrander explains, “González’s feelings toward international art exhibitions… while calling attention to how the Western canon is often seen as a backdrop or scenography for artists working in the developing world.”[3]

On the opposite wall stands Mural para fábrica socialista (Mural for a Socialist Factory, 1977-1981), a colorful remake of Picasso’s Guernica now on tiles. Facing each other, they might remind the casual visitor of an all-too-familiar festive palette, and perhaps recall a distant and distanced memory of their artistic referents—to borrow Homi Bhabha’s words, “the erratic, eccentric, accidental objets trouvés of the colonial discourse.”[4]

Emphasizing González’s formal experimentation, the overarching narrative of the exhibition highlights the Colombian artist’s critical engagement with representation, or what Ramirez calls her “meta representational practices,” in different supports —from the traditional canvas of her early career to more experimental ones such as furniture, curtains, found objects, and more recently, the columbariums at the Central Cemetery in Bogota.[5]

Structured as a traditional chronological retrospective, tracing the different stages in González’s theoretical and creative inquiries with appropriation, the curators conceived the exhibition to position her, an artist from Latin America, in the mainstream museum exhibition circuit in the United States—a move The New York Times art critic Holland Cotter described as “real news.”[6] For as Franklin Sirmans and Gary Tinterow, the directors of the Perez Museum and the MFAH, respectively, explained in their introductory words to the accompanying catalog that despite González participation in significant survey exhibitions -such as the 2017 Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985, at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles,- she “is still relatively unfamiliar to many audiences in the United States,” a lack the exhibition aimed to remedy.[7]

Countering a slowly changing mainstream museum and gallery trend in the United States which has traditionally viewed Latin American art as derivative or exotic, an underlying thread of the exhibition highlights González’s contribution to the history of 20th-Century Art while dispelling the misconception of González’s work as part of the international pop art movement, in favor of more “nuanced practice in relation to the context from which it emerged.”[8]

The retrospective achieves this by bringing to the fore González’s formal and conceptual explorations through a series of well-thought-out juxtapositions in the display. Two of the three versions of the Sisga Suicides (1965), for example, hang almost visible from the entrance. Set on a corner connecting the artist’s early explorations with abstraction appropriating images by Velásquez and Vermeer, and her more incisive copies of images from Colombian popular culture, the portraits of the young couple mark a stylistic milestone in González’s career. The first version, which bears traces of González’s overpainting on a used canvas, did not make it to Bogota, due to Covid restrictions.[9] Nonetheless, with the second and third versions standing side by side, González’s experiments with pictorial space, bright palette, stark contrasts, and flattening of the figures stand out—a necessary introduction to the artist’s pictorial vocabulary.

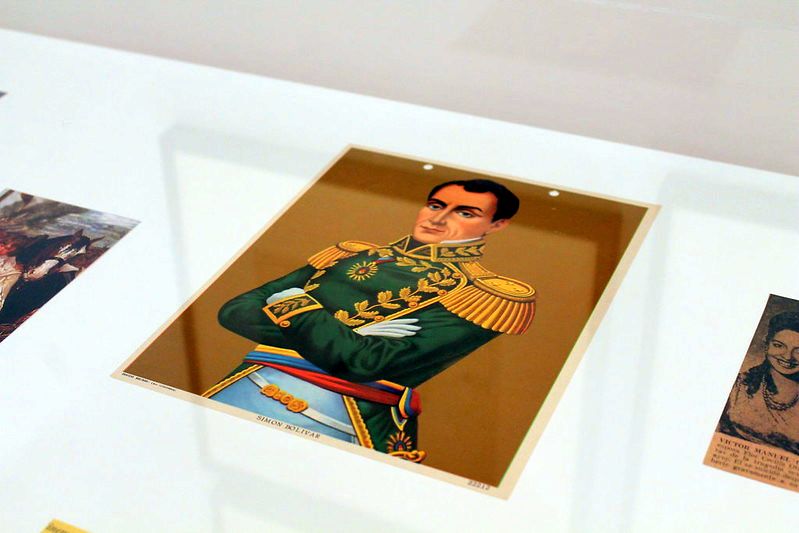

Likewise, two versions of Queen Elizabeth —La Reina Isabel se pasea por el Puente de Boyacá and Africa adios— stand along a pink and smiling Bolívar in Apuntes para una historia extensa, continuación, suggesting not only González’s interest in national (and international) heroes but also stressing her ironic use of titles. A cabinet on the far end of the gallery bears the source of González’s happy Bolívar: the textbook version of the icon, more serious and stouter, with its rhetorical heroism exhausted by the passage of time and overuse, as distributed by the local printers Gráficas Molinari.

A welcome counterpoint, Los Archivos de Beatriz González breaks with the linear narrative of the retrospective, deemphasizing the two hallmarks of the modernist art historical narrative underpinning it: artistic genius and style. Set on the ground floor of the Museum, in El Parqueadero —a gallery where young artists and experimental curatorial projects show— the display stands as both material and physical substratum to the main exhibition. A 3 x 6 m black and white photograph of the artist in overalls sitting on a scaffold, painting Telón de la móvil y cambiante naturaleza, establishes the tone of the dialogue with the retrospective upstairs. Curated by Natalia Gutiérrez and José Ruiz, González’s assistants, it shows a more intimate side of the artist, shedding light on her working process and materials, the artistic environment she came of age in, and her role in Colombia’s artistic institutions, both as a curator and director of the National Museum for 14 years.

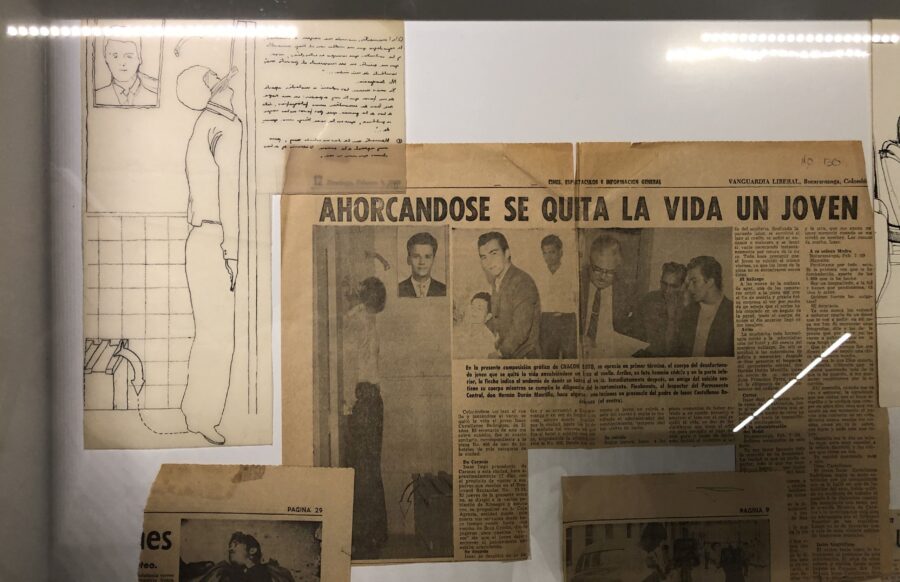

Including merely five percent of González’s substantive life-long archive, as Gutiérrez told me, it shows press clippings, sketches, postcards, posters, and letters, honoring the Colombian artist’s recent words: “The archive is the source and the basis of most of my works.”[10] The simplicity of her assertion belies deep theoretical and artistic explorations: to her, archival research, materials, and practice are “not just a source to be mined”, to borrow Andrea Giunta’s words -they are also “an object of inquiry,” a method of interpretation.[11]

Documents from González’s childhood and early career show a more human side of her work dispelling the myth of artistic individuality, originality, and genius. Several photographs of Shirley Temple, which she collected as a young girl, and images of the window displays she designed for shops in her natal Bucaramanga, suggest interesting synchronicities with Andy Warhol’s early career, an artist nonetheless whose work she came to know many years later. Postcards with stamps of Queen Elizabeth, which her brother sent her while living in London, add a layer of intimacy—as well as cultural and geographic distance—to her ironic depictions of the Queen. Articles on the multiple exhibitions spanning her long career reveal the changing, at times contradictory, reception of her work: a clipping about the 17th National Salon of Colombian artists from 1965 titled “Heated Controversy Over the National Salon: A Museum of Horrors…” depicting a radiant González by her painting The Sisga Suicides, sits side by side another one titled “What a Being with You… in New York,” published in 1997 announcing the artist’s retrospective at El Museo del Barrio in East Harlem. A final one, “The Suicides Live on,” celebrates the 50th anniversary of the controversial painting announcing its exhibition at the Tate Modern.

One of the stars of the Archives, a sketch of the furniture painting La muerte del pecador (The Death of the Sinner 1975) on display in the Retrospective upstairs, along with other of González’s bed frames, vanities, and coat hangers, expose the crevices of her working process. Set on a mock bed frame, covered by a glass protector that holds the Gráficas Molinari print on which it is based, the life-size sketch shows a usually overlooked step in Gonzalez’s artistic process: the scaling, drawing, and tracing required before applying enamel pigments. González has constantly reiterated: “The furniture [pieces] I make… are paintings that comply with the rules of traditional art; what I mean is that I do them with color pigments and brushes, and I represent something that, though already there in a photograph or reproduction is, after all, a representation of a representation.”[12] In other words, and as Traba later pointed out, the furniture’s armature functions here as a frame: providing a point of entry into the painted surface, they establish perspective, while setting in motion a game of metarepresentation.[13]

Indeed, displaying González’s furniture has always been a tricky issue, and the retrospective on the second floor is no exception. Standing on a long white wooden base that runs across two contingent galleries on the second floor where the furniture pieces are shown, the three night tables of the series titled Saluti da San Pietro, trisagio introduce the viewer to the body of work Marta Traba deemed among the most important produced in the continent during the Cold-War.[14] When they were first exhibited in 1972, González instructed the organizers of the Third Coltejer Bienal in Medellín to place them directly on the floor. The instructions aimed at enhancing the ambiguity of the support. Trading an uncomfortable line between “traditional painting” and 3D objects, exhibiting the pieces has since bewildered curators, initiating a debate which, as González’s told Katherine Chacón of the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas in 1994, “irritates me, because my paintings were always paintings, never sculptures.”[15] The elongated base here seems unnecessary: it imposes a particular way of beholding the work, fixing the structural inquiry embedded in the support.

Moving on to the third-floor galleries, which show González’s work after the 1980s, viewers will find some of the highlights of the retrospective. Showing pieces that deal with Colombia’s ongoing armed conflict and its victims—many dispersed throughout private and public collections in different countries— they not only show González’s most pungent and incisive side but also little-seen works.

Paintings such as Predicadores (2000), recently acquired by the Perez Museum and a short exhibition history in Colombia, depicts three anonymous victims lying on a common grave, their faces covered with green shrouds.[16] Hanging on a wall facing a cabinet that displays a 2003 series of self-masks based on a plaster cast mold of the artist’s face, the display suggests associations with the miraculous reproductions of the vera-icon—a beautiful way of bringing up the living presence of those who are now absent. Others, like Zulia, Zulia, Zulia (2015), a composite painting based on photographs of Venezuelan migrants which lately populate the country’s newspapers, belong to the artist’s personal collection. The multiple iterations of the news image (photograph, newspaper print, painting, and drawing) not only foreground the artist’s persistent inquiry into issues of representation, now extended to mediatic depictions of the violence in Colombia, but also invite the viewer, as María Margarita Malagón suggests “to identify, recognize, and evaluate the signs they contain […] allowing not only the interpretation of each work but also question political, social and ethical issues underlying them.”[17]

Among these galleries, the one featuring the series La Delicias, based on newspaper clippings depicting mothers and victims of a guerrilla attack in 1996 stands out. In it, two paintings, Voy desapareciendo como sombra que se alarga (2008) and Yolanda Izquierdo con libreta de apuntes of the same year, a tribute to one of the many peasant leaders assassinated in recent years in Colombia, silently stand as reminders of the unequal fight for land-rights here. The first painting depicts Yolanda Izquierdo’s flattened and slightly darkened figure. A green and yellow landscape replaces the chart the leader holds in the source image—a photograph and newspaper print sitting in a cabinet at the center of the room, providing historic and aesthetic context to González’s work. The second one, painted on paper, renders the figure—now reduced to a mere shadow— of the leader against a green background holding a blank piece of paper from an artist’s block, suggesting perhaps her fading memory and the impossibility of representation. Facing 1/500, an installation of 500 silkscreen prints (one for each year of European colonization) depicting an indigenous male figure facing the viewers while rowing away on a canoe, the story comes full circle. The works eloquently bring to the fore the ongoing displacement of indigenous communities in the long history of colonization.

In 1967 Beatriz González exhibited Notes for an Extensive History of Colombia in the 19th National Salon of Colombian Artists at the Luis Angel Arango Library, across the street from where A Retrospective and the artist’s Archives stand today. At the time, the editor of the conservative newspaper El Siglo, Arturo Abella wrote one of the most memorable critiques of Gonzalez’s art: “Plagiarism!” While for an international audience her colorful image of Bolívar, flaunting a rectangular mustache, thick sideburns, and a starry military garb, may have resembled a pop icon, locally it brought forth a heated debate over legitimacy, authenticity, national history, and notions of taste.[18] Fifty years later, both the Retrospective and The Archives celebrate the artist’s copying and appropriating practices, both as a strategy for destabilizing fixed notions of quality ingrained in the international art world, producing a critical reappraisal of the modernist discourse itself.

This text was originally written for the “Latin American Avant-Gardes” Seminar, Prof. Adrian Anagnost, Tulane University, December 2020. On the occasion of:

Beatriz González: A Retrospective (October 15-December 7, 2020) | “Los Archivos de Beatriz González (October 30, 2020-February 22, 2021) | Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia, Bogotá.

[1] Marta Traba, “Beatriz González,” Revista Eco (1979), reproduced in Marta Traba, Emma Araújo de Vallejo (ed.), 67-69. Bogotá: Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá, 1984. 67-69

[2] Ana María Reyes. The Politics of Taste: Beatriz González and Cold War Aesthetics (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019) 22

[3] Tobias Ostrander. “An Art of Contradiction,” in in Beatriz González: Una Retrospectiva (Houston, Miami, Bogota: MFA, Perez Art Museum, Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia, 2020) 289

[4] Homi Bhabha, “Of Mimicry and Man. The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse,” in Postcolonialism. An Anthology of Cultural Theory and Criticism, Gaurau Desai and Supriya Nair, eds. (New Brunswick, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press), 271.

[5] Ramírez Mari Carmen Ramírez, “The Pigments of Sorrow,” in Beatriz González: Una Retrospectiva (Houston, Miami, Bogota: MFA, Perez Art Museum, Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia, 2020) 295.

[6] Holland Cotter, “At 19 Art Shows, from Los Angeles to Manhattan, all Eyes are on Inclusion.” New York Times, September 9, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/09/arts/design/art-exhibitions-inclusion.html

[7] Franklin Sirmans, “Preface and Acknowledgements”, in Beatriz González: Una Retrospectiva (Houston, Miami, Bogota: MFA, Perez Art Museum, Museo de Arte Miguel Urrutia, 2020) 285.

[8] Mari Carmen Ramírez, Tobias Ostrander, and Beatriz González. “Charla inaugural de las exposiciones Beatriz González Retrospectiva y Beatriz González ARCHIVO”, Museo de Arte Migel Urrutia, 17 de octubre de 2020. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=372057927254283.

[9] Interview with Natalia Gutierrez, November 30th, 2020.

[10] “Auras Anónimas” Interview with Beatriz González, in Colombian Artistic Research Magazine (Carma), (Bogotá, Editorial Management, 2019), centerfold.

[11] Andrea Giunta. “Latin American Art History: An Historiographic Turn” (Art in Translation, 2017), 132.

[12] Idem, 65. (Translation taken from “Furniture as Frame,” in Inverted Utopias, Mari Carmen Ramirez and Victor Olea, eds. (Houston: MFA, 2005) 152).

[13] Idem, 66.

[14] Marta Traba, Los muebles de Beatriz González (Bogotá, Museo de Arte Moderno, 1977), 63.

[15] Katherine Chacón, “Furniture and Bad Taste: An Interview with Beatriz González” from Beatriz González, Retrospectiva (Caracas: Museo de Bellas Artes, 1994), reproduced in Patrick Frank, ed., Manifestos and Polemics in Latin American Art (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2017), 195.

[16] “Los Predicadores,” Catálogo razonado Beatriz González, Universidad de los Andes, https://bga.uniandes.edu.co/catalogo/items/show/1079. Retrieved on December 2, 2020.

[17] Maria Margarita Malagón Kurka, “Dos lenguajes contrastantes en el arte colombiano: nueva figuración e indexicalidad, en el contexto de la problemática sociopolítica de las década de 1960 y 1980,” Revista de Estudios Sociales, no. 31 (December 2008): 31.

[18] See Ana María Reyes, The Politics of Taste: Beatriz González and Cold War Aesthetics (Durham and London: Duke University Press) 2019.

También te puede interesar

CARTA ABIERTA ANTE EL INMINENTE DESPIDO DE MARÍA INÉS RODRIGUEZ DEL CAPC

En días pasados nos enteramos del despido inminente que enfrenta María Inés Rodríguez (Colombia/Francia), curadora y directora del CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Burdeos (Francia), y miembro de nuestro Comité Editorial. En esta carta,...

ARCOmadrid 2015 EN IMÁGENES

ARCOmadrid 2015, una de las ferias internacionales más importantes, celebra su 34ª edición a partir de hoy y hasta el 1 de marzo con la participación de 218 galerías de 29 países, de las…

ASÍ LO CUENTA BEATRIZ GONZÁLEZ

Más de 130 obras, entre las que se cuentan muebles, cortinas, dibujos, pinturas, recortes de periódico y señales de tránsito, componen la muestra "Beatriz González, retrospectiva 1965-2017", en el CAPC - Museo de Arte...